Amanda Partyka first came to the University to test a theory.

“I liked art. I liked math. I thought architecture might be a good place to bring them together,” she says.

It was the summer before her senior year of high school, when those who are serious about attending college start visiting some of them. Partyka was excited about WUSTL because it had something special — an intense, two-week summer camp called the Architecture Discovery Program.

“I sort of took a leap of faith when I went to that camp,” she says. “Architecture is the type of thing that’s in your blood. If it’s not for you, you’ll know right away.”

The verdict?

“It’s definitely in my blood.”

Afterward, Partyka was so in love with WUSTL that she hardly cared about other college visits that summer. Her parents teased her that she’d been brainwashed.

As an undergraduate, Partyka participated in the four-week Architecture Summer Abroad program.

“It’s probably one of the best experiences of my life,” she says. “One of my most prized possessions is the sketchbook that I brought home from Europe.”

She also came home with new insight into how we perceive and use the one thing that architecture is really all about: space.

| School of Architecture |

“As Americans, we definitely have a different conception from other cultures of how we consume space,” she says. “I remember once, when we were on a train in Berlin, we were each taking up a whole seat, but everyone else sat together, very much more condensed in their use of space. It was one little experience, not completely architectural, but it had a big impact.”

After graduating magna cum laude in 2001 with a bachelor of science degree, she worked for a year at a St. Louis architectural firm. Then it was back to the University for full-time graduate studies while continuing her job part-time.

As co-vice president of academics for the Graduate Architecture Council, she acted as a liaison between students and faculty for academic concerns and attended curriculum committee meetings with the faculty.

She also served on the admissions committee for the graduate program, helping to review applicants’ portfolios.

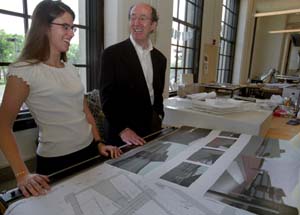

“Amanda provides a valuable insight for curriculum committee members,” says Stephen Leet, associate professor of architecture. “She is also a very precise, inventive, clear-thinking and thorough designer. That’s what impressed me most about her work.

“Those are the qualities that we hope our best students have, because those are the qualities that are needed to succeed in this profession.”

Partyka isn’t sure yet what direction her career will take, but she likes the idea of adding an architectural aesthetic to daily life.

“What I’ve come to enjoy within my studios is more community-based architecture,” she says.

Her thesis project was a hybrid program consisting of a children’s center and community museum, combined with mundane but useful spaces like a bank, post office, restaurant and small market. The project site is between the Lafayette Square and Soulard neighborhoods in St. Louis.

“It’s a little pocket that’s struggling for its own identity between places that have been redeveloped,” Partyka says. “So I wanted to bring something to this neighborhood that will sort of reactivate it and hopefully draw in people from outside as well.”

She notes that even in areas in need of renewal, the existing fabric of a community and its history should not be overlooked. Revitalization efforts should be organic rather than simply imposed upon a neighborhood, she says, building upon those aspects of the community that continue to hold it together even in decay.

And despite a host of theories about how communities function, such as New Urbanism, she says what’s natural within a city neighborhood may not work for a suburban development.

“I’d like to see developers and architects and urban planners all working together to solve these problems,” Partyka says. “The architects may have a vision that isn’t market-driven, while the developer has only that sensibility. Working together, maybe we can start getting at what people are striving for, what they really want in their lives in terms of space and aesthetic.

“Finding the answer is going to take a lot more discovery on my part as I continue to grow.”

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.