Buildings fall, books are lost, cultures and peoples forgotten. Nothing man-made is permanent, yet the process of making, the transmutation of one material into something else, is constant and ongoing.

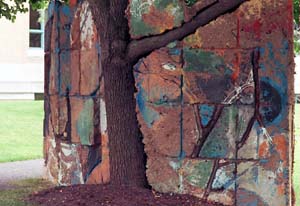

Ron Fondaw, professor and head of ceramics in the School of Art, has earned a national reputation for creating adobe structures that absorb, rather than resist, nature’s blows. Built from sand, sticks, unfired clay, pigmented plaster and locally found objects (including, in one case, a living Bradford pear tree), these large, roughly handsome sculptures weather and change with the graceful, quiet dignity of ancient ruins.

“Our culture is obsessed with the new and the perfect and the shiny,” Fondaw mused from the School of Art’s studio in Florence, Italy, where he’s teaching for part of the semester. “Other parts of the world have learned to treasure disheveled qualities. In Japan, there’s an aesthetic philosophy, wabe sabe, that describes the phenomena of material falling apart, decaying, being imperfect.

“I’m surrounded by that here in Florence,” he adds. “Water stains, crumbling facades, remnants of Etruscan villages — it’s all beautiful.”

Yet Fondaw’s adobe sculptures are just one facet of an artistic practice that ranges from traditional studio work to large-scale public commissions.

Since coming to the University in 1995, Fondaw has exhibited at more than a dozen museums and galleries across the United States and abroad; installed works at the Saint Louis Art Museum (SLAM) and the Cedarhurst Sculpture Park in Mt. Vernon, Ill.; cast aluminum bus shelters for the Forest Park MetroLink station; and completed a mural of neon light and handmade ceramic tile for the city of Columbia, Mo.

“Ron has amazing energy and diligence,” says Albert Pfarr, lecturer in ceramics, who has assisted Fondaw on several projects. “He has the fortitude to work through whatever arises, which really is half the battle.”

“I’m just an artist,” Fondaw explains good-humoredly. “That gives me a lot more freedom than saying ‘I’m a ceramic artist,’ or ‘I’m a painter.’ It gives me the freedom to move between genres and materials, to look at a specific site or situation or audience and ask, ‘What is appropriate here?'”

Early years and college

Born in Paducah, Ky., Fondaw grew up in Cape Girardeau, Mo., where his parents owned a small grocery store. He developed an early mechanical facility thanks to his father, a skilled woodworker who also refurbished old cars as hot rods.

“He’d pay us 50 cents an hour to wire-brush frames, repack wheel bearings, take transmissions apart,” Fondaw recalled. “There’s a lot of confidence-building in that.”

As a young artist, Fondaw was mostly interested in drawing and painting. He held his first one-person show in a Paducah gas station at the age of 11 and sold several oils of duck-hunting scenes.

At the Memphis College of Art, he planned to major in graphic design until a work-study job mixing clay prompted a sophomore-year epiphany.

“I didn’t want to leave,” he remembers thinking. Ceramics seemed more meditative, more filled with unexplored possibility. It also complemented his existing mechanical skills.

Constructing a kiln, for example, “you had to know about gas, about putting pipes together, about how to build burners.”

Fondaw’s first experience with large-scale ceramics came a few years later while in graduate school at the University of Illinois. A summer internship with the Moravian Pottery & Tile Works in Doylestown, Penn., provided a crash-course in Western architectural embellishment, while an African art history class (taught by the exquisitely named Anita Glaze) introduced him to new motifs and materials.

For his final project, Fondaw constructed his first adobe work, based on the architecture of Mali’s Dogon people.

“I found an abandoned clay pit in southern Illinois and spent a week in the woods,” building the piece, Fondaw recollects. The experience proved so intellectually and artistically satisfying that, “I haven’t stopped yet.”

Miami’s energy

Ron Fondaw

Birthday: Feb. 20, 199, in DetroitEducation: M.F.A., University of Illinois, 1978; B.F.A., Memphis College of Art, 1976 Family: Wife: Lynn Shepherd Fondaw; children: Andrea, 13, and Wyler, 10Hobby: HikingSelected awards: Kranzberg Award, Saint Louis Art Museum, 1998; Pollock-Krasner Award, 1996-97; Fulbright Fellowship, 1989; National Endowment for the Arts, 1988; Guggenheim Fellowship, Sculpture, 1985

After graduation in 1978, Fondaw taught at Ohio University in Athens and the following year moved to the University of Miami. As luck would have it, the young Midwesterner arrived just months ahead of the first Mariel Boatlift.

“Overnight, the city was transformed into the wild, wild West,” Fondaw recalls. Equally striking were the extremes of wealth and poverty. “You literally had bodies washing up on South Beach.”

Yet Miami’s energy — the confluence of ocean, wind and sun, the vibrant Cuban culture — made a deep impression, and Fondaw’s work grew bolder in both form and color. For Sea of Divide (1983), a suite of 10 paintings for Jackson Memorial Hospital, he purposefully set out to use the gaudiest palette he could devise.

“In Miami, you just can’t make an ugly color combination,” Fondaw quips. “Silvers and lime greens against reds, pinks and oranges; everything works.”

Meanwhile, the sharp, contrast-inducing Southern sun brought a new architectonic quality to his adobe structures, from the blocky, fortress-like Mygon (1984), with its dramatic tapering buttress, to the shambling geometries of rammed-earth works like Tymon (1985) and Taukka (1987).

Fondaw also began experimenting with Egyptian paste, an ancient yet finicky material. Its lustrous surface and rich, wet-looking colors echoed the sunken ships he frequently observed while scuba diving.

Though traditionally reserved for small figurines, Fondaw was able to make large, wall-sized works by slathering the paste over welded steel armatures. (A section of Susan Peterson’s manual The Craft and Art of Clay focuses on Fondaw’s technique.)

Perhaps no project better captured Fondaw’s sense of the Florida landscape than It Comes Ashore (1993), a public plaza for the state’s Department of Natural Resources.

Located on Marathon Key, just a stone’s throw from the Gulf of Mexico, the piece took five months to construct and features some 2,480 hand-cast ceramic tiles shaped like fish scales. Painted blue and green and installed in concentric, serpentine bands, the tiles metaphorically transformed what had been a desolate concrete expanse into gently rippling waves.

Recent projects

Since returning to Missouri, Fondaw increasingly has focused on issues of site, process and experience.

The Giving Tree, a three-walled adobe structure installed on SLAM’s south lawn in 1998, was designed to break down over a period of about six months, elegantly dramatizing the power of the natural elements. Similarly, Cedarhurst’s Whispering Walls (also 1998) centers on a large mud dome that, as it decays, will gradually reveal an oak desk and chair.

“When we first conceptualize something, we see it in our mind’s eye and it is perfect,” Fondaw explains. “It’s just the right size, it’s just the right color, devoid of light and gravity. Perfect. So the next step is to give it relativity to the real world.

“One of the reasons I started working large, and which led me into public art, is that the studio felt too safe,” he adds. “I’d look at my musician friends, who had to go on stage and make art whether they felt like it or not, and I wanted that kind of intensity. It draws out things that you never could have imagined.”

Later this spring, Fondaw will install a group of seven playful, 33-foot-tall Fiberglas “totem poles” along the walkway to The Pageant nightclub at the eastern end of the University City Loop. Tentatively titled The Vertical Loop, the piece is dedicated to the neighborhood’s rich mix of ethnic and cultural communities and includes an array of oversized pumpkins, soccer balls, tree stumps and other objects — several of which feature translucent exteriors and built-in lighting elements.

Also currently under way is Bascule Bridge, a life-size recreation of Vincent Van Gogh’s The Langlois Bridge at Arles (1888) for Saint Louis University’s Henry Lay Sculpture Park in Louisiana, Mo., just south of Hannibal.

“Typically in ceramics, we’re just building the skin,” Fondaw points out, “but when you start working large — with any material — you have to understand architecture, the way a wall holds itself up, the structural integrity of a curve or dome.

“I tell my students that you have to be a designer, a contractor and a craftsman all at the same time,” Fondaw concludes. “You need to have more than just one way of working, one way of thinking.”