During the past several years, researchers have made amazing discoveries about how the brain changes in response to internal and external events.

Injuries, changes in hormone levels, rehabilitation and myriad other events can alter the brain’s structure and function. One such influence is depression.

A few years ago, Yvette I. Sheline, M.D., demonstrated that depression could actually change the size of a key brain structure.

The hippocampus — a small, seahorse-shaped structure located deep within the brain that is important for learning and memory — was smaller in people who had been depressed than in those who had never suffered from depression.

“When I first began to do these studies, people thought I was … well, let’s just say it was not well received,” laughs Sheline, associate professor of psychiatry, of neurology and of radiology, and director, Mood Disorders Program.

“I submitted a few grant applications before the studies got funding. It was something of a struggle.”

But eventually, she got the funding that allowed her to make the remarkable finding.

“Yvette’s findings quickly made her a pioneer and a leader in this field,” says Bruce S. McEwen, Ph.D., the Alfred E. Mirsky Professor and head of the Harold and Margaret Milliken Hatch Laboratory of Neuroendocrinology at The Rockefeller University in New York and the first to chart the harmful effects of stress on the brain in animal models. “She is the person who has really demonstrated that the formation of the hippocampus changes in depression.”

Sheline later found, in a study that will be published this summer, that when depression is treated, the hippocampus doesn’t shrink in size.

“Not only is she a wonderful person and colleague, but Yvette’s work has had a significant impact on the study of depression,” says Charles F. Zorumski, M.D., the Samuel B. Guze Professor and head of the Department of Psychiatry. “She has influenced how we now think about the mechanisms involved in psychiatric illnesses. It’s one of the most exciting trends in the field.”

A constant theme

The first physician in her family, Sheline was born in Tallahassee, Fla., the oldest of seven children. Her father was a physics professor at Florida State University. Sheline’s mother had grown up in Africa, the daughter of missionaries.

When she was young, Sheline spent three years in Denmark with her family while her father worked at the Niels Bohr Institute.

“Spending time in Copenhagen gave me a very positive exposure to an international scientific community — people who loved ideas and talked about ideas,” she says. “I’m not sure the Florida of the 1950s and ’60s could have provided the same opportunities.”

Eventually, her family returned to Florida. After high school, she enrolled at Harvard College. Sheline started there intending to major in English, but she decided to become a doctor during the summer between her freshman and sophomore years. She was with her college roommate, hitchhiking through Latin America, from the Yucatan peninsula of Mexico to Peru.

“It certainly wasn’t glamorous,” she recalls. “In Chichen Itza, we slept in hammocks that belonged to a guy who handed out toilet paper, and we stayed with him and his wife in his hut with pigs and chickens.”

Living with the people in Latin America convinced her that she wanted to contribute to people’s lives in a material way. Medicine seemed to be a way to do that.

After her summer in Latin America, Sheline went to work on her pre-med courses. That led her to a series of neuroscience labs.

“I was fortunate to work with terrific scientists, and as I look back at it now, I see the same themes from those days in my current work,” she says.

“In college, I worked on the structural basis of brain plasticity in the developing cat visual system. Now, I study plasticity in the human hippocampus during depression. In college, I quantified rhodopsin molecules and sodium channels. Now, I quantify serotonin receptor binding activity in the brain.”

She studied the rhodopsin cycle in the photoreceptors of the horseshoe crab as her senior honors thesis. But as she continually reached into slimy tanks and pulled out marine creatures, she began to think again about how much more fun it would be to work with people.

She already was committed to attending graduate school, so Sheline first completed a master’s degree in neurophysiology at Yale University and then began medical school. Her intention was to combine her love for neuroscience research with her goal of contributing to people’s lives. But it would be several more years before she finally put the two together.

After medical school at Boston University and a residency in psychiatry at Harvard, she moved to California to work at Valley Medical Center in San Jose, the public mental-health system that treated the most acutely ill patients. She remembers the experience fondly, working to treat the “sickest of the sick” and to create a comprehensive system of care at a time when California funded innovative programs to treat the mentally ill.

By 1991, she was overseeing 800 employees and a $30 million budget, but she decided she was ready for a change. Although she was reluctant to leave the Bay area, after exploring the School of Medicine and the Department of Psychiatry at Washington University, Sheline decided the time and place were right for a transition back into academia.

“I feel really fortunate to have ended up in such a collegial place with such wonderful collaborators,” she says.

Focus on the brain

Initially, Sheline’s work was mostly clinical, but she gravitated toward brain imaging for her research pursuits. When she wasn’t at the hospital, she was spending time in the laboratory of Michael W. Vannier, M.D., formerly a professor of radiology who now is on the faculty at the University of Iowa. Soon, she began thinking about ways to use brain-imaging techniques to study the effects of depression.

In collaboration with Mark A. Mintun, M.D., professor of radiology and associate professor of psychiatry, Sheline has used positron emission tomography techniques to learn that people with depression have fewer serotonin receptors in the hippocampus. Those are important receptors, considering that most modern antidepressant drugs work through the brain’s serotonin pathways.

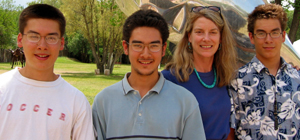

Yvette I. Sheline, M.D.Hometown: Tallahassee, Fla.Education: B.A., magna cum laude, biology, Harvard College, 1974; M.S., neurophysiology, Yale University, 1975; M.D., Boston University School of Medicine, 1979University positions: Associate professor of psychiatry, of radiology and of neurology; director, Mood Disorders ProgramChildren: Eric, a psychology major in Arts & Sciences at Washington University; Alex, a recent graduate of Clayton High School; Jason, a junior at Clayton High SchoolHobbies: Running, weight training, biking, hiking — she’ll be with her sons hiking to the bottom of the Grand Canyon over the Fourth of July. And reading; she’s part of a book club that meets once a month to discuss books such as Bel Canto, a story of hostage-taking and world-class opera in South America. A former piano player, she hopes to someday take it up again.Sheline now holds two grants from the National Institutes of Health to study neuroimaging correlates of depression. She also has a Career Development Award to act as a mentor for junior faculty members, and she was recently awarded an Independent Investigator Award by the National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Depression.

Her research focuses on brain changes called white-matter hyperintensities. Those are brain lesions that tend to occur in depressed, older patients who also have cerebrovascular risk factors such as hypertension and coronary artery disease. In collaboration with investigators at Duke University, Sheline is mapping out where in the brain those types of lesions occur and what they mean for depression and treatment outcomes.

When she’s not blazing trails in psychiatry and neuroscience research, you’re likely to find Sheline on the jogging trail in Forest Park, or spending Saturdays with a big group of sweaty joggers drinking coffee after a morning run. She also spends lots of time at sporting events. Her sons are swimmers and water polo players.

Sunday is bicycling day, and during the week she’s in the weight room. Strength training began as a way to rehabilitate her back after she suffered a ruptured disc about a decade ago. She doesn’t have imaging tests to prove it, but perhaps the rehabilitation helped restore her back injury.

After all, as Sheline’s research has demonstrated in the brain, successful treatment seems to influence both structure and function, and her strength training has been quite successful. Just ask her jogging group, her cycling buddies or those who have competed against her in area triathalons.