Ophthalmology researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified a key risk factor for the development of cataracts. For the first time, they have demonstrated an association between loss of gel in the eye’s vitreous body — the gel that lies between the back of the lens and the retina — and the formation of nuclear cataracts, the most common type of age-related cataracts.

The investigators reported their findings in the January issue of Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science.

“Most people think of cataracts as a problem that we develop if we’re lucky to live long enough, but clearly there are people who live to quite an old age and never get cataracts,” says principal investigator David C. Beebe, Ph.D., the Janet and Bernard Becker Professor of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences and professor of cell biology and physiology. “The perception that they are inevitable may have skewed our perspective about preventing cataracts, but it may be possible to prevent them if we can continue to home in on the causes of cataracts.”

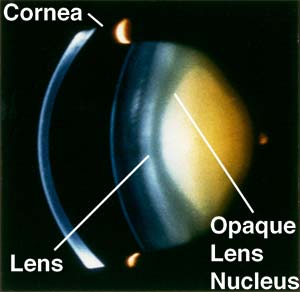

A cataract is a clouding of the eye’s lens. Cataracts are the most common cause of blindness in the world, accounting for nearly 50 percent of all blindnesses. In the United States where cataract treatment is routine, surgical removal of cataracts and implantation of replacement lenses is the most expensive item in the Medicare ophthalmology budget, representing more than half of the money spent on ophthalmic services in the country.

The idea that breakdown of the vitreous gel might be related to risk for cataracts was first suggested in 1962 by a New Jersey ophthalmologist who noticed that many of his patients with nuclear cataracts also had degeneration of the vitreous body. But this suggestion was not pursued, and it was more than 40 years before the current work from Beebe and his team demonstrated a statistical relationship between breakdown of the vitreous body and the risk for cataracts.

Beebe’s research team previously demonstrated that genes expressed in the eye’s lens tend to be those found in cells exposed to very low levels of oxygen. Several experiments convinced them the lens is normally a hypoxic — or oxygen-deprived — environment. Studies in Sweden also show that patients treated for long periods of time with high levels of oxygen tend to develop nuclear cataracts.

“Those findings helped us form the hypothesis that oxygen might somehow be toxic to the lens,” Beebe says. “And there was another key observation: the high incidence of cataracts in patients who have retinal surgery. It’s typical for retinal surgeons to remove the vitreous body in order to get better access to the retina. Within two years of retinal surgery and vitrectomy, patients develop cataracts at a rate approaching 100 percent.”

Putting all of that together, Beebe and his colleagues wondered whether there might be an association between breakdown of the vitreous body — a process known as vitreous liquefaction — delivery of oxygen from the retina and the formation of nuclear cataracts. Could it be the vitreous body’s job might be to keep oxygen in the retina from migrating forward and damaging the lens, which seems to thrive in an environment with very low oxygen?

To find out, members of Beebe’s laboratory studied 171 human eyes from eye banks, looking for cataracts and measuring the amount of liquid compared to gel in the vitreous body.

“We found that nuclear cataracts were strongly correlated with high levels of vitreous liquefaction, independent of age,” Beebe says. “In other words, if we subtracted out the effect of age on cataract formation, we still saw a very strong effect of vitreous liquefaction.”

Beebe’s hypothesis is that when the vitreous gel separates from the retina or begins to break down and liquefy, it allows fluid to flow over the surface of the oxygen-rich retina so that oxygen can be carried away in the fluid and delivered to the lens.

Currently, there is no way to measure the breakdown of the vitreous gel in living people to assess risk of developing cataracts, but Beebe’s laboratory is collaborating with a group at the University of Virginia that is working on advanced ultrasound techniques in an attempt to do just that.

He’s also collaborating with Nancy M. Holekamp, M.D., associate professor of clinical ophthalmology at Washington University, to measure oxygen levels in the vitreous chamber of patients prior to a vitrectomy and in patients who have had a vitrectomy but require a second retinal surgery a year or two later. Measuring vitreal oxygen levels in those two groups should allow the researchers to compare patients who have a gel vitreous to patients whose vitreous body is completely liquid to see whether oxygen levels near the lens really increase in eyes where the vitreous gel has been removed.

If those studies show it’s possible to identify people at risk for cataracts, Beebe says the next step would be to find ways to prevent the migration of oxygen from the retina to the lens.

“Perhaps we could replace the vitreous gel with a gel polymenr that would keep oxygen away from the lens by replacing the barrier between the retina and the lens,” Beebe says. “Those are things we haven’t thought about much because, frankly, we didn’t know what the vitreous did. Now that we’re beginning to get an idea of how the vitreous works, it may be possible to design interventions to protect the lens both in people who have had a vitrectomy and in those whose vitreous is degenerating as a part of normal aging.”