From the moment she first heard the news, Keren Kinglow knew she had to do something. For her — and for them.

As Kinglow, a pre-med student in University College in Arts & Sciences, watched the images of the terrifying tsunami unfold across the nightly newscasts, she found herself increasingly distraught.

Couldn’t sleep. Had problems eating. Was always thinking about the victims, whose numbers grew daily.

“I was completely unnerved,” Kinglow said. “It took two weeks for me to try and talk myself out of trying to go over and do something to help, and I was saying to myself ‘There’s something wrong — if I’m trying to talk myself out of it, there’s something strange going on.'”

So she contacted groups that she knew would be sending teams over to help. She had the connections, because she had been on previous missions to various parts of the world, including Russia, Venezuela and Mexico.

But surprisingly, no one wanted a pre-med student with an undergraduate degree in nursing from Oklahoma Baptist University, who had relief-effort experience and who, in the real world, is an intensive-care unit nurse at St. Luke’s Hospital in Chesterfield, Mo.

Most programs required pre-training or lots of paperwork bfore accepting individuals.

A friend comes through

Just when she thought about giving up, she received an e-mail from a friend she hadn’t spoken with in about two years.

And what the friend had to say was exactly what Kinglow needed to hear — a team from MercyWorks was going over to Sri Lanka and needed volunteers.

Kinglow made one more call.

“This was it, this was my chance,” she said. “So I jumped the gun, called MercyWorks’ hotline and said, ‘I don’t know why, but I have to go. If I don’t, I’m going to regret this the rest of my life.'”

Before she left, though, there were a couple not-so-minor details to be worked out — details like how to mention to her employer that she’d be gone for three weeks, or letting the deans and professors at University College know the same thing.

Turns out it wasn’t a problem at all.

“Keren is a very special student,” said Steven M. Ehrlich, associate dean for undergraduate and special programs at University College. “She combines intellectual rigor, experience, wisdom, an urgency about her studies and a strong commitment to the greater good.

“The vision and credit for Keren’s generous work lies squarely with Keren.”

Paula Brown, the nurse manager at St. Luke’s, was similarly acquiescent in letting Kinglow head out for a few weeks.

“She and another nurse had gone on other missions before, and they came back and were so excited about the things they had done,” Brown said.

“We had looked at pictures and asked questions about what it was like, so it was a good learning experience for the staff, too, because we don’t get to do that.”

After quickly packing her bags, Kinglow was on a plane — for 2.5 days.

Finally, she began her final descent as the plane cruised over the Arabian Ocean, the site of the tsunami.

“I was scared to look out because I didn’t know what I would see,” she said. “But you could see debris still floating in the water, even a month after it happened.

“We got there, and we’d see piles of junk, piles of belongings of people that are no longer here. I mean, children’s toys, tons and tons of junk, trees that were flattened or gone.

“You see tents, because that’s where people are living. That’s the reality. It’s really, really different. I was scared of what I would see, because this was the first real true-life disaster I’d seen. You try to prep yourself before you go, but you really can’t.”

So instead, they started prepping themselves for the task at hand — aiding those whose lives were shattered by the tsunami.

The main thrust of the group was to provide rotating clinics at various refugee camps and other places where people were living. The group included a kindergarten teacher who played with and taught children.

And this is when the magnitude of what happened really started to hit home for Kinglow.

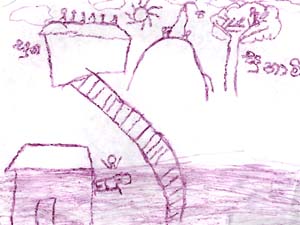

One of the ways the relief workers integrated themselves with the children was through art therapy. But instead of drawing dogs and cats and sunny days, nearly all of the children drew scenes from the disaster.

“We were getting these pictures from the kids, 5-year-olds, 7-year-olds, with dead people that were their relatives,” Kinglow said. “They are so matter-of-fact about what they are drawing.

“When you start helping people and talking to people, that’s when it gets you. Everyone has a story, everybody knows somebody who died, everybody has a relative that died, somebody knows somebody. If it’s not their family, it’s primary or secondary. And it affected the entire nation.”

But Kinglow managed to keep an even keel and helped out in a variety of roles.

“She is a very impressive young lady,” said Everett D. Holley, M.D., emergency department director for the East Texas Medical Center, who worked in the same group as Kinglow. “She has a compassionate heart for the people we worked with and took care of.

“She also would do things like just play with the kids and make people feel better.”

Unwelcome reality

After three weeks of helping the Sri Lankans, Kinglow returned home. And found her outlook on just about all aspects of life had changed dramatically.

“I had more culture shock coming here after being there than I did when I first went over,” she said. “America is so blessed with so many things, it took me a month-and-a-half until I stabilized into American culture. The first time I walked to Wal-Mart, I ended up crying because I was not used to seeing so much. Every day, it was so intense.

“I cried in Wal-Mart because there were so many things everywhere: We have food, clothes, shoes, and being in a building that’s not half in pieces was very strange. In Sri Lanka, almost every building we were in had some damage. The roof was missing, maybe one wall was standing or two — if you were lucky — so it was really hard.”

It was difficult during the day, walking around and seeing all of the spoils of American life — big cars, bigger houses, cell phones, movie theaters, fully stocked stores. But it was almost as tough at night, trying to sleep through the nightmares.

For two weeks.

So she had a contact with the missions director at First Evangelical Free Church, where she received debriefing as she gradually worked her way back into her previous lifestyle.

“You really need time to adjust because you are coming from a disaster-relief area and you get angry sometimes,” Kinglow said. “You are dealing with people with no job, no home, no clothes, no food, telling you, ‘My children are all dead, my family is all dead and the only one left is me because I made it by running up a hill and crawling up a tree and that’s how I survived.’

“Then to come here and people are, ‘Gosh, I can’t get my freaking cell phone to work,’ or ‘The tire isn’t the right look for the car that I want.’ In Sri Lanka, it’s matter-of-fact — that’s just the way it is.

“It’s mind-blowing because these children have their stories. These children, 5, 6 years old, telling you that they had to hold onto a tree to survive. It just breaks your heart.”

Kinglow recently learned she was named Miss Panama U.S. Latina 2005. As such, she will compete in the Miss Latina U.S. Pageant Oct. 1 in Cancun, Mexico.

In that role, she hopes to have a platform to further the cause of those in Sri Lanka — and to maintain a promise she made upon leaving the devastated land.

“It was tough; I didn’t want to leave,” she said. “You connect with the people. You are so close with them. I left my heart there.

“And when I was leaving, a pastor held my hand and said, ‘Pray for us, talk about us and tell our story.'”