A protein that helps the ends of growing nerve cells push forward is also involved in guidance of the nerve branches, according to a study by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

“We really thought that myosin II was just a motor, but it seems to help steer as well, ” says senior investigator Paul C. Bridgman, Ph.D., associate professor of neurobiology. “Better understanding of these guidance systems is essential to efforts to regenerate injured nerves. It’s one thing to get nerve cells to grow again, but it’s another to actually direct the regenerating nerve to its appropriate target.”

Bridgman and his colleague Stephen Turney, who is now a Ph.D. student at the University of New Mexico, reported their results in a recent issue of Nature Neuroscience.

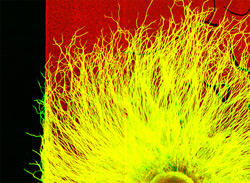

Bridgman’s lab has been studying cell growth in the peripheral nervous system for more than a decade. Growing branches from peripheral nerves form an enlargement at their tips known as a growth cone.

“It’s like a little cell of its own at the tip, with its own means to move about through different environments,” Bridgman explains. “But it’s also connected, of course, to the nerve cell branch or axon trailing behind it, and where the growth cone decides to go determines the path of the axon.”

Bridgman’s group was among the first to show that myosin II, which is similar to the myosin proteins found in muscle tissue, contracts to help give the growth cone the traction it needs to crawl forward.

They’ve also proved that stimulation from the environment affects the direction of a growing axon. Growth cones have a clear preference for laminin type 1, a polypeptide found throughout the body during development but much less common in adults. Mouse nerve cells growing across laminin in the lab will turn away when they encounter other substances and grow along the border of the area containing laminin. In addition, the mouse nerve cells avoid transitions to areas with much lower concentrations of laminin and instead grow along the boundaries of high-concentration regions.

In their newest study, inhibiting myosin II caused growth cones to lose their selectiveness and cross the border between a region containing laminin and a region that had no laminin.

“This proves that myosin II contributes in some way to the growth cone’s ability to preferentially select laminin-rich surfaces to grow on,” Bridgman says. “This means there have to be links between receptors on the surface of the growth cone and myosin, and that’s what we’re now working to determine.”

The hunt for those connections starts with a group of compounds known as protein kinases, which are enzymes that are involved in many different signaling processes and other activities. Scientists know that the nerve growth cone’s surface includes receptors that activate kinases.

“There are many different kinases that interact with the type of receptor found on the nerve growth cone, so it’s not going to be trivial to figure out which one is important for this function,” Bridgman notes.

Turney SG, Bridgman PC. Laminin stimulates and guides axonal outgrowth via growth cone myosin II activity. Nature Neuroscience, June 2005, 717-719.

Funding from the National Institutes of Health supported this research.

Washington University School of Medicine’s full-time and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked third in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.