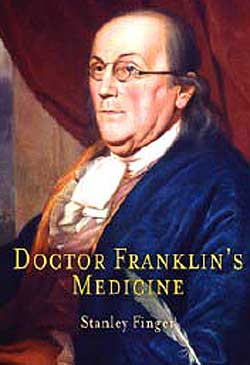

(University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006)

Professor of psychology in Arts & Sciences

Benjamin Franklin’s myriad contributions as scientist, inventor, publisher and statesman will be back in the spotlight in coming months as America celebrated his 300th birthday on Jan. 17.

While much of the hoopla will focus on Franklin’s role as an influential American diplomat, a new book suggests that he deserves considerable recognition for his important but overlooked contributions to medicine.

“Franklin played a critical role in development of modern medicine,” says Stanley Finger, Ph.D., a noted medical historian and professor of psychology in Arts & Sciences. “With strong interests in bedside and preventative medicine, hospital care and even medical education, he helped to change medical care in both America and Europe.”

In his forthcoming book, Finger presents a colorful and context-rich analysis of Franklin’s medical efforts.

Finger has written widely on the history of the brain and behavioral sciences, and his recent books include Origins of Neuroscience, Trepanation and Minds Behind the Brain. He is also senior editor of the Journal of the History of the Neurosciences.

More than a simple listing of Franklin’s medical contributions, Finger’s latest book reveals what was theorized about health and disease early in the 18th century, and shows how Franklin strove to improve medicine with careful observations, actual experiments and hard data.

“Franklin was a rare bird,” Finger says. “His broad contributions are especially remarkable in that he had no medical training and, in fact, only two years of classroom education. What is even more amazing is that he came from the colonies, where life was still a struggle — not from a major European cultural center.”

One of the unique features of Finger’s book is that he shows how Franklin’s life and medical views were partly shaped by personal events, including the loss of his son Francis to smallpox, and his own visual problems, painful gout and massive bladder stone.

He points out that it was Franklin’s appetite for books and love of learning, and how he ran his successful printing business and wanted to im-prove life in the colonies, that led him into medicine.

A lack of formal medical training was no barrier to practicing medicine in 18th-century America. In fact, only a small percentage of colonial healers had formal medical training and even fewer possessed college degrees.

“What distinguished Franklin from the myriad other colonials who practiced or dabbled in medicine was that he approached clinical medicine with the mindset of an experimental natural philosopher,” Finger writes.

“He skillfully designed experiments, collected data and compiled tables to determine trends and outcomes. He also read voraciously, contacted authorities to solicit their opinions and searched for historical antecedents. Moreover, Franklin had a remarkable ability to recognize the good ideas of others and the tenacity to move these ideas toward a productive end.”

— Gerry Everding