Can African-American theater survive?

Throughout the 1960s and 70s, African-American actors, writers and directors, inspired by the Black Arts Movement, formed dozens of regional theaters in cities around the country. Yet in recent years, several leading African-American companies — such as the Freedom Theater in Philadelphia, the Jomandi Theater in Atlanta and the Crossroads Theater in New Brunswick — have been forced to cut staff, cancel seasons or close their doors entirely.

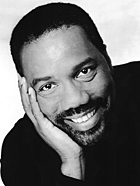

“We’ve lost a half-dozen of the larger companies,” says Ron Himes, founder and producing director of The St. Louis Black Repertory Company (The Black Rep) and the Henry E. Hampton Jr. Artist-in-Residence in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. “Nobody seems to quite understand why.

“Some companies are unable to build corporate support or do the kind of major fundraising that financially stabilizes an organization,” Himes continues. Others have been unable to find or maintain permanent performance facilities, making it difficult to build an audience base. “There’s also less federal support for the arts, which impacts state funding and in turn local funding.

“There’s certainly no lack of creativity,” adds Himes, who has a joint appointment in Washington University’s Performing Arts Department and in African & African American Studies, both in Arts & Sciences.

“We have a great cannon of African-American literature for the theater, by writers like August Wilson, Leslie Lee, Bill Harris, Cassandra Medley and Pearl Cleage; and by younger writers like Lynn Nottage and Javon Johnson. Our biggest challenge is finding the resources to preserve that cannon while continuing to develop new work.”

Himes notes that Wilson’s career is particularly instructive for African-American artists and companies. Indeed, later this month, The Black Rep and Washington University will sponsor a series of panel discussions, collectively titled “Beyond August: The State of African-American Theatre,” in conjunction with a new production of Wilson’s Gem of the Ocean, which debuts at The Black Rep March 28.

“Most playwrights are afforded a relationship with just one theater,” Himes notes. “And many theater companies can’t afford to support the entire development process,” which might include months, if not years, of workshops, staged readings and dramaturgical input. “But August had the luxury of working with a consortium of several theaters, which allowed his plays to go through an extended research and development period.”

For example, Gem of the Ocean — the ninth work in Wilson’s acclaimed 10-play “Pittsburgh Cycle,” which chronicles African-American life, decade-by-decade, in the 20th century — was workshopped at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center in Waterford, Conn., before receiving its world premiere at Chicago’s Goodman Theater in 2003. It then had runs with the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles and the Huntington Theater Company in Boston before moving to Broadway’s Walter Kerr Theater in December 2004, where it was nominated for five Tony Awards.

“By working with larger companies, August was able to give his work ample development time, financial support and production values,” Himes notes. As a result, over the years seven plays from the “Pittsburgh Cycle” were able to make the leap from regional theater to Broadway.

What’s more, “because his plays were developed nationally, they had a tremendous impact on companies and artists all over the country,” Himes adds. “August stimulated an entire generation of young writers, actors and directors.”

Building a track record

Himes himself is no stranger to Wilson’s influence. With Gem of the Ocean, The Black Rep will have produced nine plays from the “Pittsburgh Cycle,” excluding only Radio Golf, which was written shortly before Wilson’s death in 2005.

Himes launched The Black Rep in 1976, while earning a bachelor’s degree in business administration from University College, Washington University’s evening division in Arts & Sciences.

It was an exciting time for African-American theater. The playwright Joe Walker had just completed a film adaptation of his Tony Award-winning play The River Niger, originally produced by New York’s renowned Negro Ensemble Company.

That same year Wilson — who had co-founded Pittsburgh’s Black Horizon Theater in 1968 — staged his first professional play, Sizwe Bansi is Dead, at the Pittsburgh Public Theater, and also helped establish the Kuntu Writers Workshop at the University of Pittsburgh.

Still, Himes recalls that in St. Louis, “there weren’t a lot of opportunities for black artists, in terms of regional theatre and academic programs.” Similarly, “there were few outlets for audiences interested in African-American stories or theatre from an African-American perspective. So it was a matter of building a track record and finding a facility so that audiences would know where we were.”

After graduating in 1978, Himes took his young company on the road, barnstorming local colleges and generally raising visibility.

In 1981, he converted a former church into The 23rd Street Theatre, giving The Black Rep a permanent home. In 1991, Himes moved the company into the Grandel Theatre in the heart of St. Louis’ Grand Center arts and education district.

Over the years, Himes has produced and directed more than 100 plays and received numerous awards, including honorary doctorates from the University of Missouri-St. Louis and Washington University in 1993 and 1998, respectively.

Respected both in St. Louis and nationwide for his contributions to the arts, Himes has served on boards, panels and advisory councils for a number of arts organizations, including the National Endowment for the Arts, the John F. Kennedy Center, the Arts and Humanities Commission, the Lila Wallace/Reader’s Digest Foundation and the Midwest African-American Arts Alliance.

And The Black Rep — now celebrating its 30th anniversary season — has emerged as one of the nation’s largest and most respected African-American companies, reaching an annual audience of more than 150,000.

Yet, despite The Black Rep’s success, Himes feels that many of his contemporaries have come to be taken for granted within their own communities.

“Things have grown harder for African-American companies in recent years,” Himes says. “I think we’re seeing a national lack of attention to the arts. It’s an endemic problem and, unless we address it, more great African-American institutions may go under.

“The problems are certainly fixable, as are most problems in American society today,” Himes concludes. “But they will require attention, dedication and resources.

“We need a renewed commitment from the African-American community, from the philanthropic community and from the community at large.”

Panel discussions in the series “Beyond August: The State of African-American Theatre” will take place at The Black Rep March 22 and March 24 and at Washington University April 12. For more information on the topics and participants, visit www.theblackrep.org.

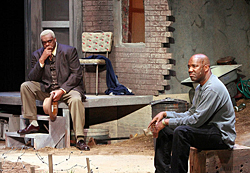

Gem of the Ocean runs March 28 to April 15 at The Black Rep’s Grandel Theatre, 3610 Grandel Square. For more information, call the Black Rep at (314) 534-3810 or visit www.theblackrep.org.

Editor’s note: Ron Himes is available for interviews. Television and radio reporters can conduct live or taped interviews via Washington University’s broadcast studio, which is equipped with VYVX and ISDN lines.