The blonde has been an iconic and highly influential ideal of feminine beauty in American culture since the mid-20th century. Yet beginning with American pop art in the early 1960s, the blonde also has become a touchstone for artistic representation and critical inquiry.

This month, the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum will present “Beauty and the Blonde: An Exploration of American Art and Popular Culture,” the first museum show to investigate the strategic use of the blonde in contemporary art. The show starts Nov. 16 and runs through Jan. 28, 2008.

Organized by Catharina Manchanda, Ph.D., curator of the Kemper Art Museum, “Beauty and the Blonde” will survey how artists have interpreted the blonde in a wide range of visual media, from prints, painting and sculpture to collage, film, video, photography and interactive Web projects.

Also featured will be a selection of advertisements, magazines, cartoons, film posters, album covers, Barbie imagery and other materials — mainly from the 1950s and ’60s — that have helped to shape popular notions about the blonde.

“Iconic Blonde,” the first of three thematic sections, traces the recurring yet often ambiguous or ironic depiction of the blonde in American Pop Art, as well as her ability to function as a critique of traditional artistic genres such as portraiture and the nude. Andy Warhol’s famous silkscreens of Marilyn Monroe, which he began creating shortly after the star’s suicide in 1962, epitomize the artist’s lifelong fascination with the double bind of celebrity and death.

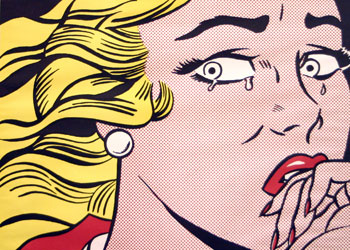

Robert Rauschenberg’s series “Reels (B C)” (1968), which appropriates frames from the 1967 film “Bonnie and Clyde” starring Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty, explores the blonde rebel through the depiction of violence in individual film stills. Roy Lichtenstein engages images of the blonde in comics while Duane Hanson, Tom Wesselmann and Mel Ramos emphasize the commercialization of sexuality.

“Deconstructing the Blonde,” the second section, surveys the ways in which artists of the 1970s and ’80s, informed by feminist thought and new conceptual approaches, began a more sharply critical investigation of the blonde ideal and its representation in popular media.

Martha Rosler’s photomontage “Bowl of Fruit” (1966-72) questions two market-driven formulas — the blonde-as-pinup and the blonde-as-homemaker — while Laurie Simmons’ “Pushing Lipstick (Full Profile)” (1979) upends depictions of the nonerotic housewife by showing a toy doll inclining towards a gigantic phallic lipstick.

Works by John Baldessari and William Wegman analyze how light and perspective can be complicit in bolstering blonde stereotypes. Dara Birnbaum’s video “Kiss the Girls: Make Them Cry” (1979) manipulates footage from the game show “Hollywood Squares” to explore the banal and sometimes bizarre gestures of male and female self-presentation.

Meanwhile performance artists such as Lynn Hershman Leeson and Pat Oleszko intervene in everyday life through fictitious characters and alter egos that question and satirize perceptions of the blonde. Performance strategies also underlie Cindy Sherman’s “Untitled Film Stills” (1977-80), in which the artist adopts the guise of a hypothetical film actress while duplicating various cinematic poses and practices.

Sherman also explores the vulnerabilities of blonde beauty in “Untitled #188” (1989), a staged photograph of an inflatable blonde doll lying prone on a pile of debris.

The final section, “Transforming the Blonde,” looks at how artists of different racial and cultural backgrounds interpret the image of the blonde. The video “Free, White, and 21” (1980), by the African-American artist Howardena Pindell, shows her conversing with a blonde white woman (actually Pindell in makeup and blonde wig) about questions of discrimination.

For the photographic suite “Untitled (Facial Cosmetic Variations)” (1972/1997), the late Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta employed wigs, makeup, shampoo and nylon stockings to distort her own visage and create hybrids that elude racial expectations.

Millie Wilson’s “White Girl” (1995) consists of a seven-foot-tall mass of synthetic blonde hair decked-out with Native American tourist trinkets. Ellen Gallagher’s printed objects in “Deluxe” (2004-05) rework images and advertisements from mid-20th-century African-American magazines, underscoring the constant challenge to define oneself amidst the cultural force field of positive and negative imagery as well as the wealth of visual references that accumulate over time.

Conversely, Nikki S. Lee’s “The Ohio Project” and “The Hip Hop Project” — in which the artist, of Korean descent, adopts Hip Hop style and dress — plays both with and against established norms, collapsing familiar boundaries and expectations.

“Beauty and the Blonde: An Exploration of American Art and Popular Culture” will open with a panel discussion in Steinberg Hall Auditorium at 6 p.m. Nov. 16.

The panel will feature Manchanda as well as feminist scholar Maria Elena Buszek and artist Lynn Hershmann Leeson. A reception will follow at 7 p.m. in the Kemper Art Museum.

The panel discussion, reception and exhibition all are free and open to the public. Regular hours are 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Mondays, Wednesdays and Thursdays; 11 a.m. to 8 p.m. Fridays; and 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays. The museum is closed Tuesdays.

For more information, call 935-4523 or visit kemperart museum.wustl.edu.