Born in Chicago, the youngest of three girls, Laura Jean Bierut, M.D., got her early exposure to medicine from her mother, Lillian, a nurse.

“On Girl Scout campouts, she always had to go along because they wanted a nurse with us,” Bierut says. “She also would go to the schools on days when they would line everybody up for vaccines with those little ‘guns’ that gave you the shots and TB tests.”

Bierut’s grandparents migrated to Chicago from Poland, and they never let their progeny forget about the many opportunities afforded people in the United States.

“My grandmother couldn’t read or write, and my parents, the first generation born here, were always very aware of how lucky they were to get an education and live in this country,” she says. “My mom became a nurse, and my dad went through school on the GI Bill after World War II. He became an accountant. They placed a high value on education.”

So they were thrilled when Bierut, now a professor of psychiatry, was accepted at Harvard University. But they also were apprehensive about her moving to the East Coast. Although her grandparents had traveled thousands of miles from Poland to Chicago, her extended family tended not to drift too far away from Lake Michigan.

“It was a big deal when my parents moved to the suburbs,” she says. “So not only going to Harvard, but just leaving Chicago was strange.”

Cambridge to Krakow

Bierut thrived in Massachusetts, graduating from Harvard after only three years with a major in biochemistry and molecular biology. She took entrance exams for medical school, but first, she did something that still seems to amaze her a little. She went to Poland for a year, to Jagiellonian University in Krakow, as a Kosciuszko Foundation Cultural Exchange Scholar.

It was a cultural immersion program designed to allow students of Polish origin to visit Poland. She would study and learn the language and culture. She also visited relatives who still lived in a small village in southeastern Poland.

The downside was that it was 1982. Lech Walesa and fellow workers had organized strikes in the shipyards and launched the Solidarity movement months earlier. The Polish government had reacted with a crackdown, so she lived under martial law.

Plus, years of stagnation under the Communist government meant that the Polish economy wasn’t doing very well.

“There were no phones,” Bierut says. “To get an international call, you actually had to go to a phone center, and there were only a couple in the whole country. The phones were in Warsaw, and I was in Krakow. I wrote letters and sent telegrams that year.”

She also learned Polish, but mostly, she says, she was reminded about the gift of good fortune.

“What that year really taught me was to thank God my grandparents came to the United States,” she says. “I had so many opportunities, and I saw firsthand that most kids there didn’t. That has changed in recent years, but in those days, things were fairly bleak.”

She did return to the United States for one week that year to interview for medical school, and, the following fall, she became a student at the School of Medicine.

Genetics of behavior

As a medical student, Bierut says, “I had no idea what I wanted to do, and I loved everything.” She eventually chose psychiatry after getting advice from the late Samuel B. Guze, M.D., the former head of the department and vice chancellor for medical affairs.

“He told me to think about what I would love doing in the long run, in 10 or 20 years,” she says. “He said we were all blessed with so many skills and so many resources and an incredible education that it would be a shame not to do what you loved.”

Bierut decided she loved psychiatry. For one thing, psychiatric illnesses involved the brain. They also had the capacity to devastate people’s lives, and there were lots of opportunities in the growing field of psychiatry research.

She says it was good advice, and she made the right choice. Charles F. Zorumski, M.D., the Samuel B. Guze Professor and head of psychiatry, agrees.

“Laura is a great colleague and mentor,” Zorumski says. “She runs a large and highly successful research program dealing with two major and costly public health problems: alcohol and nicotine dependence. Her group is untangling the contributions of specific genes and environmental influences on these disorders, and she is clearly at the forefront of her field.”

But there was one thing she did before beginning that work. During medical school, she met a dark-haired student a year ahead of her. When he was an intern and she was graduating, Bierut married Bradley Evanoff, M.D., now the Richard A. and Elizabeth Henby Sutter Associate Professor of Occupational, Industrial and Environmental Medicine in Medicine and the chief of the Division of General Medical Sciences. She jokes that after the wedding, they remained newlyweds for about three years because both always were on call.

He specialized in occupational medicine, and she began working in psychiatric genetics with the late Theodore Reich, M.D., studying genetic influences on psychiatric illnesses and behaviors, such as alcoholism, nicotine use and substance dependence.

In studies like COGA (the Collaborative Study of the Genetics of Alcoholism), Bierut and Reich examined alcoholics and their family members, got detailed information about their symptoms and collected their DNA.

Gene chips, rapid sequencing and other techniques have made the study of behavior and genetics much different now than it was when Bierut entered the field.

But her group continues to study the DNA samples collected almost 20 years ago, applying techniques that were only dreamt of when those samples first were stored. They are learning about genes and risk for illness and addiction.

In psychiatric illnesses, there is so much interplay between genes and environment that understanding how genes work, and what happens when they don’t, is only a fraction of the story.

|

Laura Bierut |

|

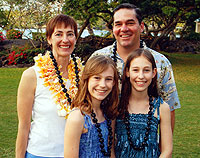

Born: March 25, 1961, in Chicago Education: B.A., cum laude, biochemistry and molecular biology, 1982, Harvard University; Kosciuszko Foundation Cultural Exchange Scholarship, 1982-83, Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland; M.D., 1987, residency in psychiatry, 1987-1991, Washington University School of Medicine; postdoctoral research fellowship, 1991, International Brain Organization, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden Position: professor of psychiatry Family: Daughters Tasha Evanoff, 15, and Tate Bierut, 12; husband, Brad Evanoff, M.D.; sisters Barbara Harlow and Susan Viola; father, the late Eugene Bierut; and mother, the late Lillian Bierut |

In some ways, she believes other branches of medicine may be slightly more advanced in understanding genetic risks and tailoring treatments to individuals, but she believes psychiatry will get there.

“We’re addressing questions like, ‘What makes us human?'” she says. “It’s our behavior. It’s our thoughts. And psychiatric illnesses harm and even destroy some of those basic aspects of our humanity. In some ways, figuring out why a person becomes alcoholic or gets hooked on cigarettes or becomes schizophrenic involves some of the most important questions we face in medicine.”

Bieoff and Evanrut

In addition to hunting for genes and speaking Polish, Bierut plays the violin. Evanoff plays the saxophone and a few other wind instruments. Their daughters are musical, too.

“We have a violin, viola, flute, clarinet, bass clarinet, three saxophones and a ukulele in the house,” Bierut says. “And there are many bicycles, too. We tandem as a family.”

Bierut and Evanoff have two daughters: Tasha Evanoff is 15. Her sister, Tate Bierut, is 12.

“We thought of using Bieoff or Evanrut, but those just didn’t sound right,” she says.

In addition to bicycling with their parents — the family spends a week each June covering the entire 225-mile length of the Katy Trail across Missouri — and playing music, both girls also speak French. A few years ago, Brad Evanoff spent seven months in France learning more about occupational medicine. Bierut was able to telecommute, and the girls had a semester of school in Paris.

“They hated it for the first two months,” she says. “The next two months were OK, and for the last three months they kept telling us they didn’t want to leave. They say they have two homes now: Paris and St. Louis.”