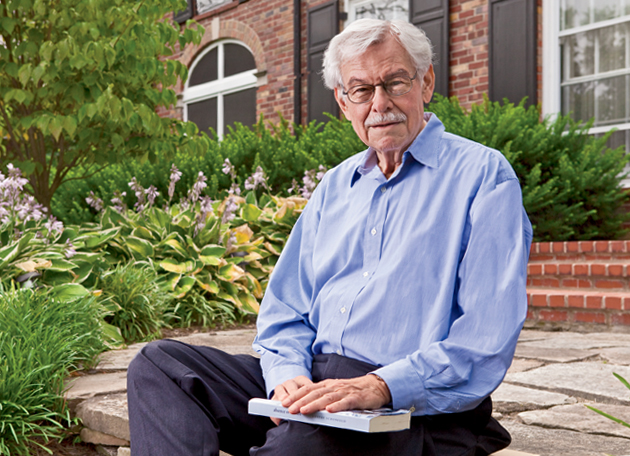

For Gustav Schonfeld, MD — husband, father, St. Louisan, world traveler, internationally respected expert on lipid metabolism and the Samuel E. Schechter Professor of Medicine at Washington University — the Holocaust is more than a historical artifact. It is something that happened to him.

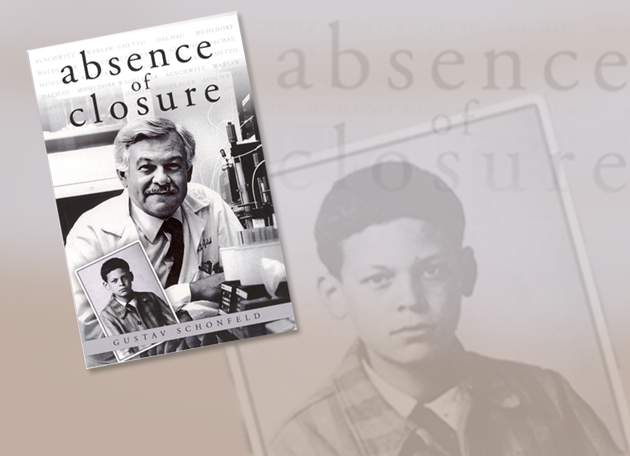

In his haunting 2008 memoir, Absence of Closure, Schonfeld recounts his long journey from Munkacs (now Mukachevo), then part of Czechoslovakia, through the Nazi camps at Auschwitz-Birkenau and Dachau, to a new life in St. Louis where he attended Washington University for his undergraduate and medical studies and established a distinguished career in academic medicine.

From idyllic to horrific

Born in May 1934 into a prosperous Jewish family, Schonfeld describes a happy childhood in Munkacs. His father was a physician — a general practitioner who saw patients in an office suite in their large, modern home.

However, he writes: “Our peaceful, pleasant life in Munkacs was abruptly disrupted one morning in late 1939, by a loud noise. Dust rapidly filled the house. We ran upstairs and found that a large part of the guest bedroom had collapsed into the playroom. Our parents told us that a cannonball had been fired by the Czech army, angry at having to vacate Munkacs in favor of the hated Hungarians, and that it had inadvertently hit the house. …

“The turnover of Carpatho-Ukraine and Transylvania to the Hungarians resulted from the land-for-peace deal Britain’s appeasing prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, had arranged with Hitler during their meeting in Munich in 1938, resulting in the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia.”

A Hungarian officer appeared at the Schonfelds’ house for a while in 1943. “He ordered us to provide him with our living/dining room as living quarters. Suddenly, Hungarian officers were in and out of the house, and we lost the use of most of our downstairs rooms. … After about three months, the orderly suddenly packed [the officer’s] bags, and they left — abruptly, with hardly a ‘thank you.’”

In 1944 the Germans invaded Hungary, appearing in Munkacs in March. “Long columns of heavily armed infantry marched past our house, accompanied by loaded personnel carriers, tanks and artillery,” he writes. “It took them more than forty minutes to pass our house. … Suddenly, uniformed German soldiers seemed to be everywhere in the city. …

“Within a few days of the invasion, the Jews of Munkacs were forced to wear yellow armbands and stars of David on our chests, curfews were imposed, and any remaining Jewish stores were closed and confiscated. After two to three weeks, Hungarian gendarmes herded the Jews from all over town into our neighborhood, which became the ghetto.”

This beginning of his family’s dehumanizing experience occurred just before Gustav’s 10th birthday. Shortly after, the Schonfelds were told they were being taken to a work camp in Hungary and were loaded into the cattle car of a train, jammed with 50 people.

“The horror had happened more than a half century ago. Yet I was still angry. Why had I not reached that … state described as ‘closure’?” writes Gustav Schonfeld, MD, in Absence of Closure.

“We spent three days in that crowded cattle car. The toilet facility consisted of one bucket. It was almost always overflowing onto the floor, so we were standing, walking and sitting in each other’s excrement. … People could not sit or lie down unless someone else stood up. …

“From the time the Germans invaded Hungary in March 1944 until the train stopped for the final time on about May 26, we had gradually been converted from civilized prosperous individuals … to a stinking, cowering mass.”

They had arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

The camp officers ordered Gustav, his mother and father to go to the left, his grandmother and baby brother, Solomon, to the right. “That was the last time we saw Grandma and Solomon. She was fifty-six years old. He was seven months old.” Other family members were sent to their death as well. Then the men were separated from the women, “and my mother went off with the cousins. For the next year we did not know whether she was alive or dead.”

After two weeks, Schonfeld and his father were loaded into another cattle car and taken to the Warsaw ghetto. When the Russian army began approaching Warsaw in August 1944, the Schonfelds and some 2,000 other prisoners were taken on a forced, three-day march, then loaded into more cattle cars and taken to Dachau in Germany. “My father told me that of the two thousand people setting off from the Warsaw ghetto, half died or were killed on the march.”

Having reached Dachau, “I felt a sense of accomplishment at having survived an ordeal, sort of what a soldier might have felt after surviving the Battle of the Bulge, except we did not have the satisfaction of shooting back at our enemies. … At that point it did not matter much to me what the end point of the walk would be. I had already proved my mettle to myself.”

A few weeks later they were shipped “again by ‘cattle-class’ train to the Waldlager Muhldorf a few hours away. The Waldlager (forest camp), although very primitive, was a spa in comparison to the concentration camps in which we had subsisted, and I was frankly glad to be there. … It was relatively small, set in a deep green quiet forest, surrounded by a single barbed wire fence. However, SS guards with dogs, guard towers with machine guns, and kapos with hoses were still very much present.”

On May 2, 1945, American soldiers liberated the camp. “It was six days shy of my eleventh birthday,” Schonfeld writes.

Coming to St. Louis

After liberation, Gustav and his father were taken to Czechoslovakia, where they reunited with his mother. When the political situation there became unstable as the Communist Party grew in power, they made the difficult decision to leave Europe and emigrate to the United States.

They came to St. Louis where relatives had settled earlier. Schonfeld’s heading for the section of his memoir that begins their St. Louis experience says it all: “Starting Over Again from the Beginning.” In particular, it meant that his physician father had to undertake an internship, which was required to take state medical board licensing examinations.

He writes: “My father became an intern at the Jewish Hospital of St. Louis in the summer of 1946, at the age of forty-three. He struggled to learn English and concomitantly to pick up the American ways of practicing medicine. … He found some of his colleagues to be sympathetic and helpful. Others were arrogant. … One of the ‘nice ones’ was Sam Schechter, who was kind and helpful. When [Dr. Schechter] was well into his eighties, he approached me and told me he was establishing a professorial chair in internal medicine at Washington University School of Medicine, and he wished me to be its first occupant. Thus, Sam was good to the father and also to the son.”

Eventually his father established a practice in East St. Louis, Ill., where “my father maintained his office until his retirement in 1978. When he retired he was charging ten dollars per visit, and East St. Louis had become an impoverished, almost completely African-American city.”

The Washington University years

Gustav Schonfeld’s long relationship with Washington University began when he entered the undergraduate program as a sophomore in 1953.

He studied with some of the eminent figures in university history, including Liselotte Dieckmann, Viktor Hamburger and Thomas H. Eliot (later the 12th chancellor). He earned his bachelor’s degree in 1956, then “entered medical school somewhat apprehensively, having heard stories of how difficult it was. But soon I came to love it, so much so that I never really left it.” He studied with notable physicians, such as Mildred Trotter, David M. Kipnis and Carl Cori, earning his medical degree in 1960.

Schonfeld’s career at Washington University School of Medicine began as an assistant professor of medicine in 1968. Over the years, he has served the university in many roles, including associate professor, professor, acting head of the Department of Preventive Medicine and chair of the Faculty Senate Council.

In 1996, William A. Peck, MD, then dean of the School of Medicine, approached Schonfeld and asked him to serve as head of the Department of Internal Medicine.

“The offer came as a genuine shock,” Schonfeld writes, “as the chair of medicine was not a position I had ever aspired to nor expected to achieve, certainly not at Washington University. I believed that the distance between Munkacs, Auschwitz, and a chairmanship at a place like Washington University was a distance simply too great for me to traverse.”

Absence of closure

But underlying his successful career, his happy marriage and raising a family were the memories of what he and his family had suffered. The genesis for his book dates back to 2000 when he was visiting a maternal aunt in Budapest and realized that he was very, very angry.

“The longer we stayed [in Budapest],” he writes in the memoir’s preface, “the angrier I became, as I realized that the Shoah (Holocaust) in which the Hungarians had played an -important part was ‘old news’ to the current generation. … Completely catching me off guard was the magnitude of the anger I felt. The horror had happened more than a half century ago. Yet I was still angry. Why had I not reached that happy state described as ‘closure’?

“The provocation was too severe, I thought. Perhaps closure for some hurts is impossible.”

Excerpted by Mary Ellen Benson, assistant vice chancellor/executive director of University Marketing & Design, from Absence of Closure, copyright © 2008, Gustav Schonfeld. Reprinted with permission. Absence of Closure is available at amazon.com.

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.