ACT I

THE SCENE: The office of Gaylyn Studlar, PhD, the David May Distinguished University Professor in the Humanities and director of the program in Film and Media Studies in Arts & Sciences.

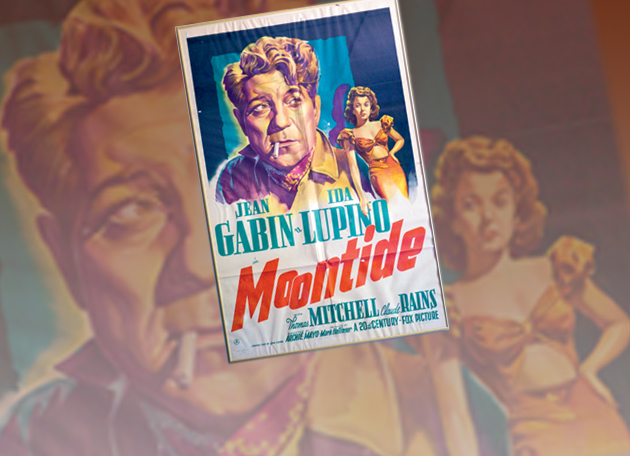

FADE IN TO CLOSE-UP: Behind her desk hangs a poster for the 1942 film noir melodrama, Moontide (see above). In the foreground is the craggy French actor Jean Gabin, who is leering over his shoulder at a distant but voluptuous Ida Lupino. She is dressed as skimpily as the censors of the day would allow.

STUDLAR: “My interest in film studies came originally from film theory. I was very much focused on gender issues in film. For example, look at this poster. One interpretation would be the camera reproduces male viewing — and women are coded for erotic impact. But Gabin, with a sidelong glance and cigarette dangling from his mouth, also is quite sexy and is certainly a star who appealed to women.”

“My interest in film studies came originally from film theory. I was very much focused on gender issues in film,” Studlar says.

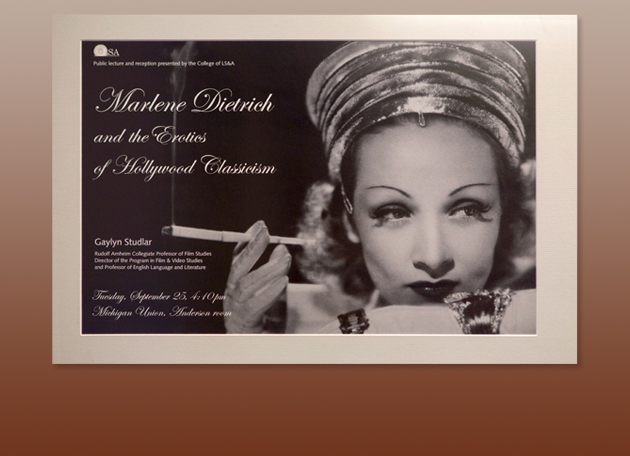

FADE IN TO SECOND CLOSE-UP: On another wall of her office is a picture of glamorous German star Marlene Dietrich (see above). Her early 1930s films, directed by Josef von Sternberg, represent gender roles very differently. In The Devil Is a Woman, an older man warns a younger acquaintance to stay away from “Concha,” who has ruined his life. But the young man doesn’t listen: He falls desperately in love — and, in the end, she breaks his heart, even while the older man pursues her yet again.

While earlier theorists perceived these films as examples of men attempting to control women, Studlar advanced a different theory in a 1988 book, In the Realm of Pleasure: Von Sternberg, Dietrich, and the Masochistic Aesthetic. She decided that the films actually showcase male masochism, as the male star falls self-destructively under the domination of the woman.

STUDLAR: “So, in the von Sternberg films, contrary to many Hollywood films, where the woman is presented as submissive or merely ‘eye candy,’ she is more than sexy and anything but submissive. She is ‘guilty’ of dominating men — and she doesn’t care. She’s insolent as well as maddeningly elusive.”

Studlar finds Hollywood and filmmaking so fascinating because of the multiplicity of viewpoints. It is not monolithic. For her, Hollywood provided a rich source of research topics, among them film noir, masculinity in film, cross-media stardom in the 1930s and Orientalism in film. And it led to an exciting career at various institutions with six books to date, plus dozens of scholarly articles.

Since arriving at Washington University in January 2009, Studlar has already worked to expand offerings in the program in Film and Media Studies to include a graduate certificate. In the future, she would like to further globalize the course offerings and include more classes that explore the intersection of film and other media.

GARY WIHL, PHD, DEAN OF THE FACULTY OF ARTS & SCIENCES AND THE HORTENSE AND TOBIAS LEWIN DISTINGUISHED PROFESSOR IN THE HUMANITIES: “Gaylyn Studlar brings a wealth of knowledge to the study of film, the newest art form of the 20th century. In a series of major studies, she opened new ways to understand film as an industry, a force of popular culture and a powerful influence on our perceptions of romance and heroism. We are fortunate to have her at Washington University, where I’m confident she and her colleagues will continue to build an exciting program.”

ACT II

THE SCENE: It is 1958. Focus on a small movie theater in Lubbock, Texas, where Donley, babysitting his younger sister, has dragged her to see the science-fiction thriller The Fly, with Vincent Price. At home, they watch old Warner Brothers movies, such as the 1931 movie Public Enemy starring James Cagney, on their black-and-white television.

STUDLAR: “That is how I got interested in films of the ’30s. But I didn’t go to college with film studies in mind. How could anybody make a living watching movies? That was just impossible!”

In fifth grade, Studlar began playing the violin and then shifted to the cello, winning a scholarship for private lessons. She pursued music performance at Texas Tech University and afterward as a master’s student at the University of Southern California. But something wasn’t quite right.

STUDLAR: “I just didn’t feel I was getting all the intellectual stimulation that I wanted. Since I was at USC, with its strong cinema school, I started taking a few film classes. And I thought: ‘Eureka!’”

In those pre-video days, she had to drive all over town to find revival houses that were showing older films. On opening night, veteran stars would appear, like MGM soprano Kathryn Grayson or Esther Williams. To finance graduate school, Studlar took a full-time job in the cinema library, which held an annual dinner to honor a Hollywood great. At these events, she met Debbie Reynolds, Mae West, George Cukor, Charlton Heston, among others.

After earning her PhD, she spent three years teaching at the University of North Texas, eight years at Emory and then 14 years at the University of Michigan, where she was named the Rudolph Arnheim Collegiate Professor of Film Studies. There, she led the initiative to turn the film studies program into a department, which grew to 17 faculty and 250 majors.

ACT III

THE SCENE: A classroom at Washington University. Students are eagerly discussing sexual politics in film noir and hard-boiled detective fiction, using such ’40s and ’50s movies as The Maltese Falcon or Kiss Me Deadly.

NICHOLAS TAMARKIN, GRADUATE STUDENT IN COMPARATIVE LITERATURE:“Professor Studlar is that rare scholar who appears, sadly and yet somehow appropriately, only to exist in the movies. She is not simply an extraordinary mentor, but one who demands of her students the same focus and care that she gives to her own projects. I can think of no higher praise than this.”

Last year, the program in Film and Media Studies had three tenure-track faculty and three full-time lecturers, along with some 50 undergraduate majors. This size, says Studlar, allows for smaller classes and close contact between teachers and students. So far, she has taught “Film Historiography,” “Film Theory,” “Women and Film,” and “Stardom”; soon she hopes to add “John Ford Made Westerns,” as well as “British Cinema,” “Hollywood on Hollywood” and “Orientalism in Film.”

Yes, students enjoy watching movies, she says, but the film courses give them much more. They are learning how to think critically and analytically about what they see on screen, and then to write persuasively. What’s more, these are transferable skills.

For a forthcoming book, Precocious Charms: Juvenated Femininity in Classical Hollywood Stardom, Studlar has been doing her own analysis of films featuring women who play young girls or adolescents — a phenomenon called “juvenation.” Early film star Mary Pickford, known as “America’s Sweetheart,” used child roles to build her career. The teenaged singer Deanna Durbin became Hollywood’s highest paid actress. Studlar analyzes how Durbin’s stardom relates to cultural expectation attached to classical music, as well as to age and gender in the late ’30s.

STUDLAR: In a sense, the waif-like Audrey Hepburn also fits this description. “I have a chapter on Hepburn — flat-chested, girlish, virginal, but clothed in Givenchy haute couture — and how she formed a contrast to voluptuous ’50s femininity represented by stars like Marilyn Monroe or Jane Russell.”

The next act in Studlar’s academic career is a book about the role of Catholic organizations, such as the Legion of Decency, in pressuring Hollywood to censor films. Film directors lived by a 1930 Production Code for motion pictures, drafted by St. Louis priest, Daniel Lord, S.J. Further constraining them were local and British censors, the latter who enforced the “twin beds” rule on screen, even for married couples.

Outside of work, Studlar likes to bicycle, kayak, garden and sew. She shares a William Bernoudy-designed home with her husband, Thomas Haslett, who teaches elementary education. She says she is enjoying St. Louis and the warm, collegial atmosphere at Washington University.

ELIZABETH CHILDS, PHD, CHAIR AND ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ART HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY IN ARTS & SCIENCES: “Gaylyn Studlar combines experience as an academic leader with the kind of energy, directness and open personal manner that make it a pleasure to work with her on new ideas for the curriculum. She is a terrific asset to the humanities!”

Candace O’Connor is a freelance writer living in St. Louis.

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.