For all the searching an archaeologist does for clues to past human societies, says anthropology and environmental studies Professor T.R. Kidder, PhD, “sometimes, sites find you.” Like the time in 1989, when a forester in Louisiana phoned Kidder, an authority on Mississippi basin geoarchaeology, to say he’d just climbed a lone hill in an alluvial lowland where no hills should be. This discussion contributed to Kidder’s research focus on mound societies for some 10 years.

Another site found him several years ago through an international call from Liu Haiwang, PhD, senior researcher at China’s Henan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, who invited Kidder to join his archaeological team on a vast river plain in central China. A river expert and self-described “mud guy,” Kidder and different graduate students have spent the past three summers (and, at press time, are there again) pursuing “an incredible opportunity at a phenomenal site. It is just spectacular!” says Kidder, chairman of the Department of Anthropology in Arts & Sciences.

A river expert and self-described “mud guy,” Kidder and different graduate students have spent the past three summers (and, at press time, are there again) pursuing “an incredible opportunity at a phenomenal site. It is just spectacular!” Kidder says.

Excavations at the China site have revealed an exquisitely preserved rural farming village, Sanyangzhuang, buried 2,000 years ago when an onslaught of silt-laden river water inundated the area. Tucked 15 feet under the earth’s surface in a protective blanket of fine-grained sediment, the settlement might never have been discovered at all, Kidder says, had a Chinese construction crew in 2003 not attempted repeatedly to dig an irrigation ditch in the area. The crew kept hitting roof tiles and even what seemed to be a wall. When they notified local authorities, the Henan Province archaeological institute sent Liu to investigate. He dated those remains to the Han Dynasty, which ruled from 206 B.C. to A.D. 220, following China’s unification. The period is often thought of as a golden age of peace and relative stability, rising prosperity and intellectual advances.

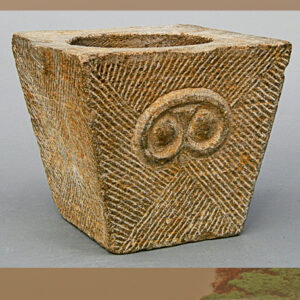

In time, Liu’s archaeological group concluded that the ancient farming settlement had been interconnected and remarkably well-off, despite its remote setting. Some of the tiles from collapsed roofs are imprinted with characters reading “long life,” an inscription popular with well-to-do Chinese of the day. Cart tracks and human footprints heading out of town suggest that the residents escaped with their lives, but they left all their possessions, which seem flash-frozen in time. Looms that were still in use and grinding stones stand silent; iron-tipped farming tools lay where they were dropped.

So far, four extended-family compounds, about 500 feet apart, have emerged. Each has a series of rooms and covered front and back courtyards inside an earthen wall. Toilets and deep, brick-lined wells are set in surrounding open areas. Because fossils of mulberry leaves, signaling silk production, appear at Sanyangzhuang along with copper coins, Kidder says the area may mark the beginning of China’s Silk Road trade.

Just beyond the compounds, fields appear with furrows so intact that they look newly plowed, and probably cover several square miles. “This is just the beginning,” Kidder says, explaining that buried within a few square miles of the excavated compounds are 11 more homesteads that they know of. The scientists also have discovered signs of a walled city a mile and a half away from the Sanyangzhuang site. “If it’s preserved in the same way that Sanyangzhuang is preserved, we will truly have a kind of Pompeii,” says Kidder, referring to the Roman city buried in ash a few decades after Sanyangzhuang disappeared.

“We also have a ‘thing,’” Kidder continues, “a massive area perhaps 10,000 meters square, that’s full of cultural remains. We don’t know what it is — it’s much too big to be a house, and there are no walls that we can see. So we’ll excavate that, as well.”

Because historical texts of the Han period focused chiefly on wealthy imperial cities, the archaeologists at Sanyangzhuang are developing the first record of life on China’s plains. Kidder anticipates that the potentially huge and complex site will require increasing numbers of experts as questions proliferate. He is already collaborating with a pollen expert from Hebei Normal University and a geologist from Peking University.

“The most beautiful excavation in the world”

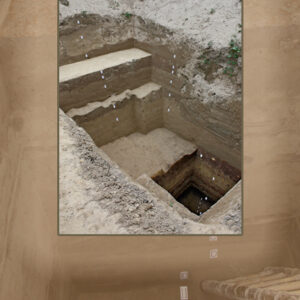

The site at Sanyangzhuang has surrendered even more. “In 2009,” Kidder says, laughing, “I naively asked my colleague Mr. Liu whether his crew could excavate a profile, a pit, that would cut through the Han period of occupation. I told him I needed to look at the geology, the stratigraphy of the time.” Liu’s plentiful workers dug several impressive holes, one of which was roughly 12 feet across and 43 feet deep. “It was staggering!” Kidder says. “It’s the most beautiful excavation in the world! It’s stunning!”

What the hole allowed Kidder to see is nothing less than the entire past 12,000 years of environmental history — work that will preoccupy scholars for untold decades to come. Cross-cut from the earth’s surface down are a series of cultural layers, each separated by differently colored silty strata from separate major flood events. “Now I can look at both cultural behavior and the environmental behavior that set the context for the cultural layers,” he says.

Extensive sampling around the area has convinced Kidder that he and his Chinese colleagues now have a complete and quite comprehensive understanding of the stratigraphy and the general chronology of events.

Beginning at the top and using approximate dates in each case going down, one layer dates from the Tang period of about A.D. 907 to 619; the layer beneath that is from the Han era of the site; three feet below that is a layer dating to the Warring States period of perhaps 300 to 400 B.C. About four feet beneath the Warring States layer is one dating to the late Neolithic or early Bronze Age, about 1600 B.C.; three feet under that is a layer dating to 4000 or 5000 B.C., and below that, “you’re into the early Holocene, about 8000 to 10,000 B.C. — the end of the last Ice Age,” Kidder says. “From a purely stratigraphic point of view, from an environmental-history point of view, it is a truly unprecedented record. Not only that,” he adds, “each of the dateable levels is sealed off from the next by silt. We expect the cultural remains to be very well preserved.”

“Sanyangzhuang has much to say to the modern world”

“Understanding what happened in A.D. 14 is one way of thinking about today — by considering how people did or did not respond to issues about their own effect on the environment and about what the environment could teach,” Kidder says.

Kidder went to China to develop the Sanyangzhuang research projects with his colleagues through the International Center for Advanced Renewable Energy and Sustainability (I-CARES) and the McDonnell Academy Global Energy and Environment Partnership (MAGEEP). As his work has developed and expanded, he and Michael Frachetti, assistant professor of archaeology and a specialist in prehistoric nomadic societies in central Eurasia, often discuss their work. “What is so impressive,” Frachetti says, “is that with T.R.’s compelling geoarchaeology and methodology pioneered in one of North America’s most important river valleys, he brings a new perspective that the Chinese are eager to further integrate into their work. He is a scholar of world proportions.”

Kidder emphasizes that the history of Sanyangzhuang has much to say to the modern world. The ways the village’s economically advanced people affected their environment and contributed to the depredation of certain of its resources may have contributed to the flooding, for example. Further, Han China and modern China have certain connections. “Understanding what happened in A.D. 14 is one way of thinking about today — by considering how people did or did not respond to issues about their own effect on the environment and about what the environment could teach. Archaeology isn’t [only] about the past. It’s about the present and future.”

Judy H. Watts is a freelance writer based in St. Louis and a former editor of this magazine.

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.