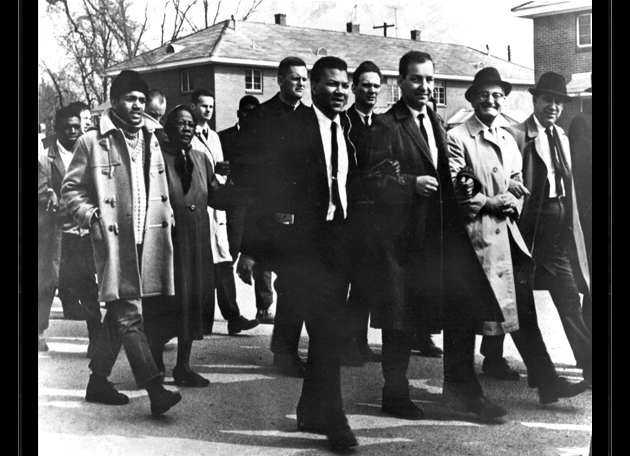

During a 1965 broadcast of Judgment at Nuremberg, a film about Nazi war crimes, ABC interrupted the program to show images of African Americans being brutally beaten in Selma, Ala. Marching for their voting rights, as activists crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge, they encountered state and local police wielding nightsticks and tear gas. This shocking violence was taking place not in Nazi Germany, but in 1960s America.

Filmmaker Henry Hampton, AB ’61, catalogued this event, which became known as “Bloody Sunday,” and other pivotal moments in the fight for civil rights in an epic documentary, Eyes on the Prize. Comprising two parts and 14 episodes, the renowned Eyes on the Prize details the events that shaped the civil rights movement. The series spans decades, and it includes rare firsthand accounts and archival footage, making the documentary a crucial source of U.S. history.

Washington University Libraries houses the complete archives of Hampton’s production company, Blackside, Inc., including all the materials originally created and gathered for Eyes on the Prize. Further, as the sole guardian of the Henry Hampton Collection, University Libraries recently received a $550,000 grant, one of the largest in its history, from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The grant’s purpose is to preserve Part I of the series, Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Years, 1954–1965, as well as its accompanying interview outtakes.

“It is the major document of one of the most important periods of American history,” says Shirley K. Baker, vice chancellor for scholarly resources and dean of University Libraries.

Part I includes six episodes, which debuted on PBS stations in 1987, while Part II, America at the Racial Crossroads, 1965–1985, and its eight episodes, debuted in 1990. Collectively, the series attracted more than 20 million viewers and won more than 20 major awards, including a Peabody Award for excellence in television broadcasting.

The documentary features interviews with well-known activists, such as Coretta Scott King, Harry Belafonte and Jesse Jackson, as well as unrecognized supporters and various opponents of the movement. Former chairman of the NAACP Julian Bond narrates the series.

“It is the major document of one of the most important periods of American history,” says Shirley K. Baker, vice chancellor for scholarly resources and dean of University Libraries. “It is fair, even-handed, gripping. The series includes the full range of opinions presented fairly, with no agenda except to testify what happened. Because watching it is so gripping, it really changed how people think, and it was very important.”

An important collection finds permanent home

In 2000, two years after Hampton’s death, Blackside’s nonprofit affiliate, Civil Rights Project, Inc. (CRPI), began looking for a permanent home for Hampton’s archive. At the time, James E. McLeod, dean of the College of Arts & Sciences and vice chancellor for students, served on the board of CRPI. McLeod subsequently informed Baker of the opportunity.

Baker and her team at University Libraries drew up a proposal for the archive, highlighting Hampton’s historical connection to St. Louis and the university. The proposal also indicated deep faculty interest and the university’s ability to create a film and media archive division with designated staff, as well as space at West Campus. Support would come from library film and technology endowments.

CRPI selected Washington University over contenders — WGBH (Boston public broadcasting), the Library of Congress, Indiana University and the University of Georgia — as the official recipient of the collection. Then, in 2002, the Henry Hampton Collection came to Washington University. Arriving in four tractor-trailers, the materials for every Blackside production, including original interviews, stock footage, audio, scripts, research and photographs, are now stored in the Film & Media Archive’s climate-controlled vault, located at the West Campus Library.

Henry Hampton: the man behind the masterpiece

The late Henry Hampton was no ordinary filmmaker. His legacy continues today with the filmmakers he trained, who strive to emulate his meticulous organization and even-handed style.

Considering his acumen, Hampton was not always a filmmaker, or even someone who intended to be one. Born in St. Louis, he attended Washington University and graduated with a major in English literature. He began medical school at McGill but dropped out before heading to Boston.

Once there, Hampton became fascinated with the city and wanted to learn more about the area and its people. To satisfy his curiosity, he became a cab driver, where he was exposed to all kinds of individuals.

While driving the cab, Hampton met Royal Cloyd, who hired Hampton to be the editor for the Annual Year Book of the Unitarian Universalist Association.

Throughout his life, Hampton was interested in the fight for civil rights. Consequently, he marched in Selma, protesting the unfair voter registration laws and death of civil rights protester Jimmie Lee Jackson. This experience left him a changed man. Leaving his job at the UUA, he formed Blackside, Inc. His mission: to document these stories for future generations.

His filmmaking was truly innovative: He scoured news stations for relevant film footage and conducted unprecedented research, ensuring that every line in a script was supported by at least two sources.

He kept all original footage, including uncut interviews, and hired an archivist to manage the material. He also brought in experts to educate production staff.

Interview with the cousin of a catalyst

When Hampton was 15, he was greatly affected by the death of 14-year-old Emmett Till.

While in Mississippi visiting relatives, Till was killed by white men for whistling at a white woman who was working in a store.

Hampton opens the first episode of Eyes on the Prize with an interview with Curtis Jones, Till’s cousin who had traveled with him from Chicago to Mississippi.

According to Jones, the boys felt the difference between their hometown and the Deep South. Although both boys had been warned about being careful around whites in Mississippi, Till was naïve, and the significance of his mother’s warnings didn’t fully register.

Jones’ interview paints Till not only as someone who made national headlines (and hence became a symbol of a movement), but also as a fun-loving prankster.

“Emmett Till was the type of guy who loved fun and jokes; he loved to play a joke on people for some laughs. He laughed all the time, you know,” Jones says in the uncut interview.

“Emmett Till was the type of guy who loved fun and jokes; he loved to play a joke on people for some laughs. He laughed all the time, you know,” Jones says in the uncut interview. “The day he got killed, we went fishing in a little mudhole down there. And, I’m fishing, and all of a sudden I hear some water splash. And he’d throwed a log in the water and said, ‘That was a big fish just jump up over there,’ you know. And he’d break out and laugh, you know. That’s the type of guy he was.”

A few days after the whistling incident, Till’s body was found in the Tallahatchie River with a 70-lb cotton gin around his neck. White men had come to his grandfather’s house, beaten and killed him before throwing him in the river.

Till’s open-casket service garnered national attention. The entire public saw the incomprehensible brutality inflicted upon a child as a result of racism. This incident helped awaken the country to civil rights abuses.

“During the filming of Eyes on the Prize, Julian Bond went to Mississippi to stand on the banks of the Tallahatchie River where Till’s body was found,” Baker says. “He then stood in front of the store where Till had sealed his doom. Bond says that the hairs on the back of his neck stood up. People were standing there, watching him. They drove by in pickup trucks with gun racks on them, and it was truly frightening because people didn’t want the coverage of that controversial event.”

A timeless project

When University Libraries applied for the Hampton Collection, it pledged to preserve and promote the resource “for educational and scholarly use by students, faculty and filmmakers, as well as by institutions and individuals in the surrounding community and beyond.”

The Film & Media Archive lives up to its promise and tries to answer every request, be it from a Washington University student or a researcher from across the globe.

“We make sure that scholars who are interested can have access to the materials,” Baker says. “We don’t just own this for us. We own this for everybody.”

“Hampton was very adamant about Eyes on the Prize having a place in the classroom,” says Nadia Ghasedi, film and media archivist. “He wanted to tell these stories to students and inspire a new generation of activists.”

With support from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, the Film & Media Archive collaborated with WGBH to create lesson plans incorporating collection materials for K–12 teachers all over the country. The plans, which include interviews and discussion questions, meet social studies curriculum requirements. They are web-accessible and free.

“Hampton was very adamant about Eyes on the Prize having a place in the classroom,” says Nadia Ghasedi, film and media archivist. “He wanted to tell these stories to students and inspire a new generation of activists.”

But the requests are not only from academics. For example, the Film & Media Archive assisted a journalist working with the Civil Rights Cold Case Project, an initiative that investigates and seeks justice for unsolved civil rights murders. The journalist requested Blackside’s FBI file regarding the murder of Jimmie Lee Jackson, an unarmed black activist who was shot and killed by a state trooper. The trooper had never been indicted. The journalist had learned of the Blackside files, which had less redacted material than current versions, from a Blackside producer. The additional evidence these files provided assisted the journalist in writing his article, and, ultimately, the state trooper was sentenced.

More than looking to the past, however, Hampton hoped his work would help people contextualize history in a way that could better the future.

“By telling the story of America’s civil rights movement, he wanted to raise awareness of the civil rights injustices currently happening,” Ghasedi says. “Preserving this iconic work will continue to do just that.”

Michelle Merlin, Arts & Sciences Class of ’12, is a summer writing intern in University Marketing & Design.

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.