Thomas Jefferson fires the public imagination as powerfully today as he did in 1776, judging by the excitement generated when 74 volumes from his “Retirement Library” were discovered this year in Washington University Libraries’ Special Collections. The report appeared in 150 newspapers and television broadcasts around the world, in many languages. Enthusiastic emails and Facebook postings piled up for both university and Monticello scholars and staff.

“I expected it to be big,” says Endrina Tay, a Monticello librarian whose research helped uncover the Jefferson trove, “but I was surprised at the overwhelming, across-the-board excitement.”

“I expected it to be big,” says Endrina Tay, a Monticello librarian whose research helped uncover the Jefferson trove, “but I was surprised at the overwhelming, across-the-board excitement.”

The response testifies to the enduring power of Jefferson’s ideas, which, Tay argues, are as relevant today as they were when the American colonies broke away from their English overlords. “Ideas about democracy, about freedom, about education still resonate,” Tay observes. “What’s happening in the Middle East, for instance, all comes back to these ideas that Jefferson was very much involved with.”

The level of excitement reflects as well the books’ historical significance. Jefferson expert David Konig, PhD, Washington University professor of history in Arts & Sciences and of law, says these volumes are valuable for what they reveal about Jefferson’s last decade. “They tell us much about his last years and what he was thinking and doing in a particular time in his life that isn’t as studied,” Konig notes.

A central figure in American politics for decades, Jefferson looked forward to leaving politics when his second presidential term ended in 1809, Tay says. Though very much a senior statesman who entertained the powerful of America and Europe at Monticello, he turned his interests chiefly to his family and to founding and building the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

The turn is certainly reflected in the Retirement Library’s contents.

Jefferson had sold his substantial personal library — 6,700 volumes, one of the largest private libraries in the country — to Congress in 1815, to replace the congressional library destroyed when the British burned the capitol in 1814. His collection formed the core of what would become the Library of Congress.

With a voracious appetite for learning, Jefferson continued to acquire books and build up a new library, known now as his Retirement Library.

“When you look at the library,” Tay explains, “you will see that the composition is different. Prior to 1815, he had a lot of books on political subjects, on government, especially on law, but in his Retirement Library there are far fewer law books and books on political subjects. It was much more dominated by the classics, which he loved.”

It included history, philosophy, even some medical books. “They’re really for his personal enjoyment,” Konig says.

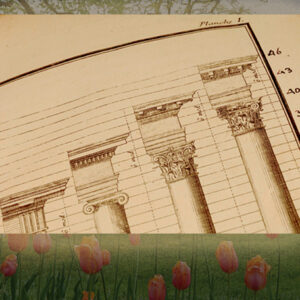

Architecture formed part of this collection, and indeed eight of Washington University’s volumes are architecture books. The University of Virginia was Jefferson’s passion late in life; he was deeply involved both in its design and in the development of its academic program. “He had enormous faith and hope about subsequent generations,” Konig says. “He really wanted each generation to improve upon the last. So his work on the university was quite consuming in his latter years.”

Thus, Monticello staff members were thrilled to find among Washington University’s holdings a volume in French, Parallele de l’architecture antique avec la moderne or A Parallel of the Ancient Architecture with the Modern by Fréart de Chambray. “When Jefferson was building, giving instructions to his workmen for the University of Virginia, he actually made specific references to this particular edition,” Tay says. “We know he used it in designing the pavilions on the Lawn” — the heart of the university grounds — “because he made references to it in his correspondence.” Five of the 10 pavilions were based on Chambray; the other five were based on designs by Andrea Palladio.

“These books are tied very much to his writings,” Tay says. “To be able to look at his correspondence, to look at the physical structures at the university, and to look at the actual pattern books that he used — to be able to tie all that together is significant.”

“This volume is what Jefferson used when he designed the University of Virginia, and we had not seen it until this find,” Tay says. “These books are tied very much to his writings. To be able to look at his correspondence, to look at the physical structures at the university, and to look at the actual pattern books that he used — to be able to tie all that together is significant.”

The architecture books and his notes in the margins also reveal Jefferson’s remarkable mind. “He was not a dilettante. His interests were very deep,” Konig says. “In the architecture books, for example, it’s quite clear that his marginalia were put in there really to understand and ponder the foundational principles of architecture, even though he knew that many of the things in his architecture books could not be built in Virginia.”

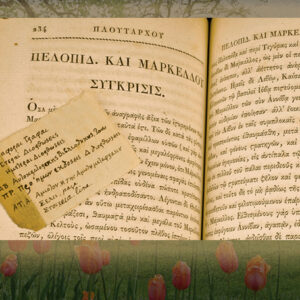

This quality of deep study set Jefferson apart as a true Renaissance man, with a command of many disciplines and many languages. The books themselves are in French, Italian, Latin, Greek; indeed, only one of the university’s 74 volumes is in English. In one of the Greek books, Jefferson actually corrected the Greek grammar in his distinctive hand. He corresponded with many of Europe’s key thinkers and often received manuscripts from them to review.

“Jefferson’s mind was a far-reaching and restlessly inquisitive one that, typical of the Enlightenment, tried to organize information into a coherent whole in which all fields of knowledge were related to each other. So he applied his thinking about nature to his thinking about politics, his thinking about politics to his thinking about philosophy,” Konig explains.

“For Jefferson, knowledge is not just skills. It’s not just reading books; it’s engaging the books, responding to them and challenging them.”

“For Jefferson, knowledge is not just skills. It’s not just reading books; it’s engaging the books, responding to them and challenging them.”

A remarkable bit of bibliographical sleuthing uncovered the books in Special Collections, where they had lain unidentified for more than 130 years.

Jefferson died deeply in debt. “Very few large farmers in Virginia were doing well,” Konig explains. Additionally, he lived lavishly, though not self-indulgently, Konig argues. “He was supporting so many members of his own family, and Monticello became a kind of magnet for people interested in keeping the Revolution alive. He was very much an older sage who felt obligated to entertain, so in the last years of his life, he was still buying hundreds of bottles of wine, for instance.”

But what really devastated him financially was the crushing debt of a relative for whom he had co-signed a note. In the 1819 financial crash, the borrower went bankrupt, and Jefferson was left the debtor. When he died, he owed more than $100,000.

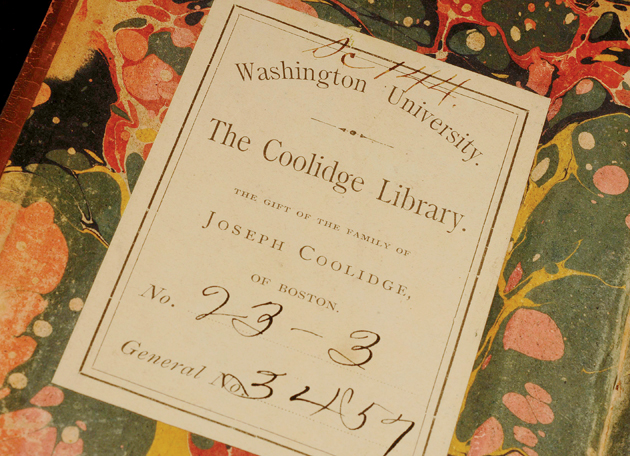

To settle the debts, his estate sold his slaves, books, even Monticello itself. But Jefferson’s grandson-in-law, Joseph Coolidge of Boston, arranged to purchase some of the books when they were auctioned in Washington, D.C., in 1829. These volumes joined Coolidge’s own library and subsequently disappeared from the historical record. That is until October 2010, when by a fluke Ann Lucas Birle, another Monticello scholar, discovered an 1880 Harvard Register item: Harvard alumnus Edmund Dwight, Joseph Coolidge’s son-in-law, gave the Coolidge collection (Coolidge was also a Harvard alumnus) to his cousin (another Harvard alum) Washington University co-founder William Greenleaf Eliot, for his fledgling university in St. Louis. (Dwight and Eliot’s great-grandfathers were brothers.)

In 1880, no one was aware that any Jefferson books were in the collection; Jefferson had used a very unobtrusive sign to mark his books. The collection doubled the size of the university library, and most of these books were on the open shelves until about 1970.

Birle passed the Register item on to Tay, who since 2004 has been creating a publicly available database of all of Jefferson’s books. Birle knew Tay was trying to track down extant Jefferson books from the 1829 auction. Tay drew up a list of the books Coolidge had acquired and contacted Washington University, where Erin Davis, curator of rare books, investigated and discovered the 74 volumes. The university and Monticello announced the discovery in February 2011.

As the third-largest repository of Jefferson’s books (after the Library of Congress and the joint holdings of the University of Virginia and Monticello), Washington University will draw increasing numbers of scholars.

“These books had been essentially lost for 130 years,” Tay observes.

The discovery has opened up a new relationship between Washington University, Monticello and the Jefferson scholarly community. As the third-largest repository of Jefferson’s books (after the Library of Congress and the joint holdings of the University of Virginia and Monticello), the university will draw increasing numbers of scholars. It has already loaned six volumes to Monticello for display through 2011. In addition, staff members from the university’s Special Collections and Monticello are collaborating to reconstruct the original Coolidge library — an endeavor they hope will uncover additional Jefferson books. “It could be that there are a few more that belonged to him,” notes Shirley K. Baker, vice chancellor for scholarly resources and dean of University Libraries.

Finding this Jefferson treasure trove, Baker observes, has been the biggest surprise of her university career — “one of the most thrilling things that can happen to a library staff.”

Tay agrees. “This,” she says, “is the find of a lifetime.”

Betsy Rogers is a freelance writer based in Belleville, Ill.

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.