In 1970, young Navy officer John Gannon came back from Vietnam with greater maturity and a brand-new academic goal: He wanted to attend graduate school in history. But he faced two giant obstacles. First, as an undergraduate psychology major at Holy Cross, he had taken only three credit hours in history, not nearly enough for most doctoral history programs.

Further, campuses across the country were embroiled in tumultuous protests against the Vietnam War. Already, four students had died at Kent State, killed by the National Guard, and in response demonstrators had burned the small ROTC building at Washington University. How would a new veteran fare on campus?

To explain his newfound interest in history, Gannon made his case in a detailed letter to Washington University, where eminent historian J.G.A. Pocock and his admissions committee read it and were convinced. With Pocock’s support, the admissions committee not only admitted Gannon but also awarded him a generous fellowship. Gannon was thrilled, and when he arrived on campus, he made another happy discovery.

“All the time I was at Washington University, I never received anything but respect and encouragement from the students and professors, which was in contradiction to the revulsion you saw on campus for the war,” says Gannon today. “They did not take it out on an individual.”

By the end of his stay in St. Louis, he had received a PhD (1976) in Latin American studies and welcomed two sons into the world. He also happened to attend a lecture on Cuba given by a senior analyst at the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). This led to a visit to CIA headquarters in Langley, Va. — and from there to an event-filled CIA career, culminating in a two-year stint as its deputy director for intelligence and his final four years as chairman of the National Intelligence Council.

During his tenure, Gannon traveled to several continents, met foreign leaders, and witnessed, from very close-up, some world-changing events. President George W. Bush awarded him the National Security Medal, the nation’s highest intelligence award. Today, he has left government service and serves as president of the intelligence and security arm of BAE Systems, a global aerospace, defense and security company.

“The experience of working in the intelligence community is a great one,” Gannon says. “It exposed me to the best information and very smart people, and I am very grateful that I had those opportunities.”

Forging a career

Gannon grew up in Worcester, Mass., the sixth of nine children. His father, a public school teacher, had served in World War II; his two brothers were Marines. At Holy Cross, Gannon was not a strong student at first, but by the time he graduated, he had earned first honors. Next, he spent a year in Jamaica as part of the Jesuit Volunteer Corps, which gave him a taste of life abroad.

A second taste came in Vietnam, where he was an engineering officer on an amphibious landing ship. “Coming back, I fully understood that we had lost some 56,000 members of the military, and I was aware that the political tide in the country had turned. So the opposition to the war did not surprise me,” Gannon says.

While at Washington University, he savored campus intellectual life. His adviser was Rick Walter, a Latin American expert; he was a student assistant for Henry Berger on U.S. labor history and studied with Rodney Berthoff on American social history. The vibrant discussions stimulated him and gave him, he says, “a more sober view of a complex world, past and present.”

German operations

At the CIA, he started out as a Latin American analyst, traveling abroad, and then he became part of the presidential briefing staff on security issues. From there, he did a tour in Europe for the State Department, and when he returned to the CIA, he eventually worked his way up to directing European analysis during the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe.

In 1989, he was the deputy CIA director for European analysis under John McLaughlin just as the pace of political change in that region suddenly began to accelerate. Poland had elected a non-Communist upper house of its parliament; communism in Hungary had collapsed. But few believed that East Germany would founder, since the Soviets regarded it as the linchpin of their security.

“Suddenly, the Germans were on top of the wall, shouting and coming over it,” Gannon says. “And the guards, in a complete breakdown of discipline, essentially let them come through checkpoints.”

Then on the evening of Nov. 9, Gannon and McLaughlin watched on their office television, incredulous, as events unfolded at the Berlin Wall. With John Chancellor anchoring the coverage, NBC News was running live footage of the scene: Eager crowds approached the wall, and the guards, who were confused by the eddying political currents, did not have the stomach to shoot them.

“Suddenly, the Germans were on top of the wall, shouting and coming over it,” Gannon says. “And the guards, in a complete breakdown of discipline, essentially let them come through checkpoints. Only two days before, a senior German diplomat had told me that he didn’t think this would happen in his lifetime. So for us, this was a really emotional moment.”

The Balkans

Later, as director of European analysis and deputy director for intelligence, Gannon saw Yugoslavia disintegrate. First, the Yugoslav Republics of Slovenia and Croatia broke away, and then Bosnia declared its independence. Fighting broke out between Bosnian Muslims on the one side and Serbs from Bosnia and Serbia on the other. Gannon briefed officials in the region, including the president of Albania, and he spent a great deal of time on the growing crisis there.

For one meeting with Bosnian Serbs, his colleagues had hired a female Serb translator who had lived in Sarajevo when it was a thriving, diverse city but had now been forced to relocate to Pale, a Serbian stronghold, where she felt like an embittered exile. Gannon, the translator and the Serbs all met in a crowded Pale restaurant. When a waiter approached to pour water into their glasses, someone bumped him, his pitcher tipped, and water streamed over the translator’s head.

“She looked at me and said: ‘Who says the Serbs aren’t the aggressors?’” Gannon says. “I thought that was a great line of humor in what was a really tragic situation.”

Moving up at the CIA

As deputy director for intelligence from 1995 to 1997, Gannon supervised all the CIA’s analysts and launched a major reorganization of the agency. From 1997 to 2001, he chaired the National Intelligence Council, a group of senior experts that developed assessments about national security, bringing all the U.S. intelligence agencies to the table.

By the time the aircraft hit the Pentagon and the World Trade Center in 2001, Gannon had retired from the CIA and was working at a global analysis company in Georgetown. He was chairing a staff meeting when the first tower was hit — and he thought it was an accident. Then the second tower was struck, and he knew that it was a terrorist attack.

“I remember well that I viewed the events of that day as a major tactical success for Al Qaeda, but also as a strategic failure because Osama bin Laden apparently believed that attacking symbols of U.S. commercial, military and political power could actually deal a mortal blow to the strong institutions that undergird them,” Gannon says.

For a time, he regretted that “our government seemed to let fear trump resolve in dealing with the terrorist threat.” When Osama bin Laden was finally killed in spring 2011, Gannon says, “I felt that justice had been rendered and that the tireless, decade-long efforts of our intelligence, diplomatic and military personnel had been vindicated.”

New threats from within and without

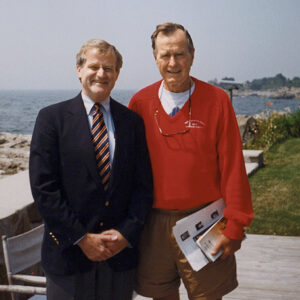

As part of his extraordinary career, Gannon has met senior foreign and U.S. officials, including Richard Nixon (“a man with tremendous intellectual capability and a unique mastery of foreign policy issues, but, as we know, greatly flawed in his personal qualities”); George H.W. Bush (“particularly gracious and ‘analyst-friendly’; he loved to get a ‘gaggle’ of analysts around him and be briefed by them”); and Bill Clinton (“a rapid reader and absorber of intelligence, who didn’t have much patience for sitting down and talking to analysts about it”). For three years, he worked for former CIA head William H. Webster, JD ’49, a man whom he greatly admires — and today serves with him on a committee to create scholarships for Washington University students.

“The extension of U.S. power abroad will always depend on our strength at home,” Gannon says.

Along with his work at BAE Systems, Gannon also teaches as an adjunct professor in Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service. Once staff director for the House Select Committee on Homeland Security, he still testifies before Congress on U.S. security issues, which include strengthening our economy, our energy policy and the quality of primary and secondary education, particularly in math and the sciences.

“In all these areas, the United States is increasingly vulnerable,” he says. “This should concern us more than the continued buildup of intelligence services, which are clearly improving in their capabilities to assess external threats. The extension of U.S. power abroad will always depend on our strength at home.”

Candace O’Connor is an award-winning freelance writer and editor based in St. Louis.

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.