Tahiti, a land conjuring ideas of the exotic and “primitive,” helped shape the work of fin de siècle painters Paul Gauguin and John La Farge (which in turn helped shape Western perceptions of the islands). Further, these perceptions help explain more than just how art and artists work. They tell us volumes about the colonial experience, why we travel and what we perceive when we get there, says art historian Elizabeth Childs, PhD.

“As it was in the late 19th century, a condition of modernity is that one is often frustrated with, or alienated by, the complexities and pressures of urban life. One of the most recurring fantasies of modernity is of temporary escape through travel, displacement and even emigration to an allegedly simpler place, such as a Pacific island,” says Childs, associate professor and chair of the Department of Art History & Archaeology in Arts & Sciences (http://arthistory.artsci.wustl.edu/people/childs_elizabeth-c). “The story of these artists highlights how, in travel, we are generally not what we might believe ourselves to be — we’re never purely blank slates, capable of experiencing the new in an unbiased and fresh way.”

Childs’ forthcoming book, Vanishing Paradise: Art and Exoticism in Colonial Tahiti, 1880–1901 (University of California Press, fall 2012), synthesizes her ongoing work on French Polynesia and works by Gauguin, the American La Farge and his famed traveling companion historian Henry Adams, as well as lesser-known colonial photographers.

“This study shows how any quest is usually framed by long-standing expectations of places, of other societies and, indeed, of ourselves,” Childs says.

The myth of primitivism and “imperialist nostalgia”

The book, which gathers together for the first time more than 135 illustrations of pertinent works from museums and private collections worldwide, is already stirring interest in the scholarly art world.

“For the last decades, as we art historians have been rethinking the concepts of modernism, Elizabeth Childs’ work on Gauguin and on primitivism has been essential to that effort,” says Patricia Mainardi, professor of art history at the Graduate Center of The City University of New York. “All of us in the scholarly community are eagerly awaiting the publication of her study on Tahiti and the myth of primitivism.”

Travel to faraway places in the late 19th century (and perhaps even today) was animated in part by an “imperialist nostalgia,” according to Childs.

“Back then, there was already a sense that the West had lost something that might possibly be regained through exposure to these worlds,” Childs says. “Yet, once these artists arrived and experienced the inevitable disappointments of a colonial society, they feared they had gotten there a moment too late. They experienced a sense of nostalgia and the impossibility of recuperation of an essence of natural or cultural purity, believing it was just beyond the grasp of the European or American visitor.”

Although Gauguin and La Farge never met (the Frenchman arrived June 9, 1891, five days after the American had left for good), both used their Tahitian experiences to advance their artistic careers, albeit with differing artistic approaches and personal predilections.

“Managed adventures” Vs. “the cocoanut and bread-fruit life”

La Farge and the well-connected Adams (a wealthy direct descendant of two American presidents) were treated as official American ambassadors and mingled with the French and Tahitian ruling classes during an apparently chaste four-month stay. They sought what Childs terms “managed adventures” in an age before packaged luxury travel, even bringing La Farge’s valet to Tahiti and hiring local cooks.

Gauguin, conversely, found a Polynesian mistress, worked a menial job for the French government, and stayed for years — living what a perhaps envious La Farge termed “the cocoanut and bread-fruit life.” La Farge went so far as to call the Frenchman “wild and stupid” in a letter to Adams.

Gauguin exhibited a modernist primitivist perspective, while La Farge often composed his landscapes as pastoral scenes, representing the exotic with a stylish classicism.

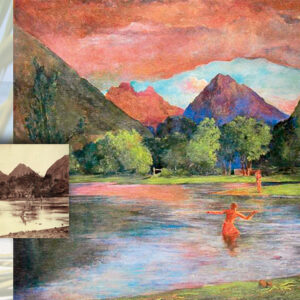

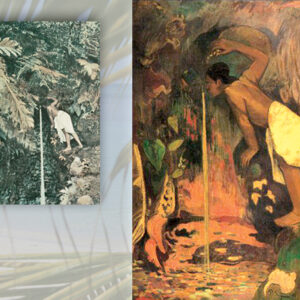

Yet both La Farge and Gauguin influenced following generations of artists, sometimes even painting similar idyllic scenes taken from the same colonial photographs.

Gauguin exhibited a modernist primitivist perspective, while La Farge often composed his landscapes as pastoral scenes, representing the exotic with a stylish classicism.

“Gauguin engages in a sexual voyeurism and in a kind of sensualizing of what he imagines tribal peoples are supposed to be,” Childs says. “Gauguin is interested in poetry, in effect, in the drama of it all. He’s not interested in being precise but wants to take elements from this culture that can help him weave a good story, a good myth.”

La Farge, however, sought to portray Tahiti with more precision of natural detail.

Both largely avoided depicting the presence of Euro-American culture on the islands, Childs says. And both were conscious of the potential of their Tahitian experience to advance their careers.

“For both La Farge and Gauguin, this was absolutely a careerist move,” Childs says. “La Farge, who had failed in his decorative arts company, was looking for a sort of regeneration but also for a new set of motifs. He ended up using watercolors to do it.

“Gauguin was conscious of his relationship to the Paris art market, choosing his subjects — especially in the last two years — to suit the Paris art dealer Ambroise Vollard. Those last years of his life in the Marquesas were funded by Vollard, so Gauguin could leave his miserable office job in Tahiti and just paint.”

Also, like most travelers, both Gauguin and La Farge went to Tahiti with prior notions of what island life might be like.

“Of islands that have a mythic presence in the modern imagination, Tahiti is probably the most famous and least visited, in spite of major incursions into modern tourism in the last few decades. The name conjures idylls of relaxation, bounty, freedom and beauty,” Childs says.

“This is still largely due to the works of art by Gauguin and La Farge, and to earlier reports of Tahiti widely circulated in Europe by 18th-century European explorers — Cook, Bougainville, Wallis and Bligh. Their writings left what I call the ‘foundational myths of Tahiti’ as a particular kind of place.”

Tahiti’s foundational myths

In her new book, Childs traces five key themes from the late 18th century — themes still deeply influential in the late 19th century of La Farge and Gauguin, and ones that often remain operative today:

• A geographical stereotype of Tahiti as nature’s garden, an island of plenty.

• A cultural stereotype of Tahitian people as athletic, indolent and sensuous — and its corollary of Tahitian women being generous with sexual favors.

• A perception of Tahiti as a land of supernatural powers, populated by ghosts, spirits and gods.

• A belief that Tahiti was a land of warfare and violent ritual — an 18th-century perception the French sought to neutralize and one that does not appear in Gauguin’s work.

• The view that Tahiti after its contact with Europe was now a vanishing paradise. As early as 1802, only 35 years after the French first arrived, the “real” Tahiti was perceived by Europe to be dying.

“My book looks at how Euro-American artists and writers negotiate in their art their belief in the loss of this ‘authentic’ paradise after Tahiti became a French colony,” Childs says.

“These were seen by the traveling artists” — La Farge, Gauguin and Adams, as well as other artists and writers — “as key characteristics of an authentic Tahiti,” Childs says. “After its establishment as a French colony in 1880, this ‘real’ Tahiti was perceived by visiting artists and writers as fading and disappearing.

“My book looks at how Euro-American artists and writers negotiate in their art their belief in the loss of this ‘authentic’ paradise after Tahiti became a French colony,” Childs says. “They regarded themselves as privileged last witnesses to this precious domain that would not survive encounters with modernity.”

But all those artists and writers were wrong, Childs says.

“Tahiti adapts and continues to thrive in a unique cultural idiom not defined by or replaced by any imperial power, in spite of its political and economic dependence, first as a colony and now as a modern territory of France.”

Rick Skwiot is an award-winning freelance writer based in Key West, Fla. Visitrickskwiot.com.

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.