Why do black athletes have a particular kind of social, political and cultural significance in the United States? How did this importance evolve, and how is it tied to a larger context — and to American history?

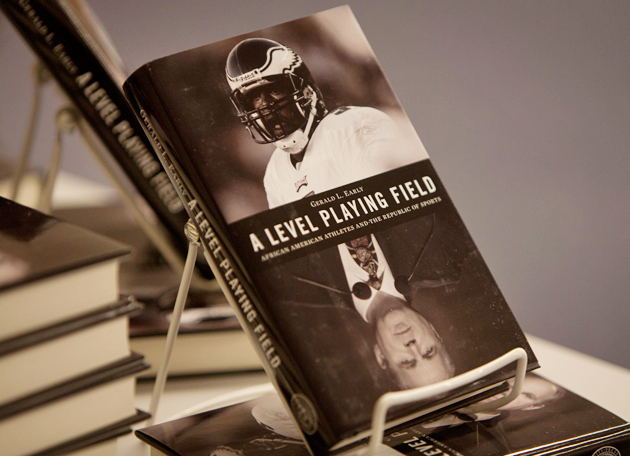

Questions, not answers, knock the messages out of the park in A Level Playing Field: African American Athletes and the Republic of Sports by Gerald Early, PhD, the Merle Kling Professor of Modern Letters in Arts & Sciences and director of Washington University’s Center for the Humanities.

Part one of the 263-page hardcover, published in April 2011 by Harvard University Press, consists of three lectures Early gave in 2004 at Harvard University’s W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research. Part two consists of three previously published essays from Chronicle of Higher Education, The Nation and Time magazine. Together, they form “an excellent template from which to work when we want to look beyond the platitudes that mark the dialogue about race and sport,” according to a review in The Wall Street Journal.

Washington Magazine asked Early to consider the following questions related to his exploration of the intersection of sports and race.

Washington: Why investigate the impact of black ballplayers on American culture?

Early: What athletes do means something beyond just what’s happening on the field because what’s going on in the field, by some measure, is irrelevant. It doesn’t really matter very much how fast somebody can run or how many home runs somebody can hit — it doesn’t change the quality of life for people. Yet these contests speak to people in some profound way because of what sports represent.

Sports actually wind up having incredible significance to people because athletes are highly symbolic figures in our culture. Athletes represent a set of values, an ideology, a set of myths, an affirmation of what we would like to believe about ourselves.

Washington: Why do you call sports a true meritocracy and how does that relate to the rise of blacks in the field?

Early: If a quarterback throws 35 touchdowns in a season, that’s 35 touchdowns. And it means whatever it means within that context, which in that case would mean that the quarterback is very good.

Sports are, for the most part, quantitative and, seemingly, objective. Sports are the ultimate triumph of a sort of social science view of the world: Sports are measurable and even, on some level, predictive, if not precisely predictable. An athlete is chosen on the basis of how well he or she can do the job, purely on measurable skill. That is why sports are admired as a true, an ideal, meritocracy.

Washington: You write that former Negro Leaguer and the first black Major League Baseball player Jackie Robinson is an example of affirmative action that appeals to both liberals and conservatives. How so?

Early: It appeals to conservatives because Jackie Robinson got where he did because there was no question he was qualified to be a ballplayer. So as far as merit goes, he deserved to be there because he was better than any other player who was going to be playing the position he was playing. It’s a triumph of color-blindness.

It satisfies liberals because he was a black guy who came up and was recognized, adding diversity to the Dodgers and to baseball. So while liberals are concerned about merit, too, they’re more concerned with the idea of diversity and the fact that he made the game more democratic, transformed what the sport represented.

Washington: Parts of the book focus on Rush Limbaugh’s 2003 statement about Donovan McNabb, then with the Philadelphia Eagles, that, “The media has [sic] been very desirous that a black quarterback do well.” You say that was not untrue. Yet Limbaugh lost his ESPN gig over it. Can you explain?

Early: I think it’s true that the press is, by and large, invested in seeing black people — or any minority people — succeed in positions that white people normally have had.

I think people felt they had to be on the right side of the question, so they had to condemn what Limbaugh was saying. But they kind of missed the point, because he was indicting the media; he wasn’t saying anything about black athletes, except that the press might be so invested in the politics of racial injustice that it will overlook black mediocrity. But the accusation of black mediocrity itself is another charged political issue, which, ultimately, entangled Limbaugh.

Washington: But was the comment racist?

Early: While Limbaugh’s comment was true, it was, by itself, not racist. But the intention may have been racist. His statement was in no way meant to try to understand the dilemma or the complexity of the position of the black athlete.

The comment was meant to be another potshot at affirmative action and at the general liberal trend to overlook black mediocrity. If you listen to Limbaugh’s show, you know he hates affirmative action. He was accusing the press of promoting black quarterbacks even when they weren’t that good.

The other side of the coin is a longstanding issue for African Americans, that the pursuit of sports is a controversial topic in among blacks. If Limbaugh had brought that out in addition to what he was saying about white liberals enabling black mediocrity, then I would say that he really was trying to be serious about this whole issue.

Washington: What kinds of stigmas are associated with black athletes?

Early: Many black people feel that black athletes get criticized and denigrated when they do something wrong — much more so than white athletes do if they do the same thing.

When Carolina Panthers quarterback Cam Newton — who was a huge college star — was going to be drafted, there was a lot of commentary by white sportswriters that he didn’t work hard enough, and that he was going to find it really hard to understand how to read defenses and run offense when he got into the NFL.

Retired Hall of Fame black NFL quarterback Warren Moon was very upset about these kinds of remarks. Moon thought what they were really saying was, “He’s not bright enough to do it — because the quarterback is a thinking position — or he’s not motivated enough,” which is another way of saying that he’s lazy.

Of course, white quarterbacks, such as Tim Tebow and Eli Manning, have been criticized as well, but clearly, in this case with Moon and Newton, blacks feel strongly that criticism that borders on racial stereotype is unfair.

Blacks also are stigmatized because the general public tends to think sports are something that blacks seem almost genetically disposed to do well, better than whites, although only a fraction of professional sports is dominated by black performers. In this way, though, blacks have been seen as all brawn and no brains, and as natural entertainers.

Washington: A theme that comes up several times in your book is the “black athlete as a slave” analogy popularized by some African-American commentators. What fault do you find with this analogy?

Early: I think it’s a poor analogy. I don’t think people should make analogies about something they find unfavorable or that they don’t like to something like slavery or the Holocaust, because those are really horrific human tragedies. I know why people do it: because they feel black athletes are exploited and exist in a powerless relationship with those who pay them. This is not actually true, but sports can be an ugly, deceptive business. There may be troubling aspects to black people being athletes, but they’re not slaves. They’re paid — and successful ones are paid a lot of money. Not even college athletes are slaves. They chose to be athletes, and people don’t choose to be slaves.

Washington: How do you think the slave analogy figured into the challenge of St. Louis Cardinal Curt Flood to baseball’s reserve clause, which allowed teams to trade players?

Early: That Curt Flood used the slave analogy was not surprising, given that period in history. The 1960s was a time of great social and political upheaval in the United States. You had the civil rights movement, the black power movement, the anti-war movement, and you had the clenched fist salute at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City.

Flood felt he was standing up against something that was oppressing him. The issue of the reserve clause and baseball players being oppressed got conflated with the idea of his being a black man and being, as he put it, a slave, and being victimized. So it kind of became a racial issue although it’s not a racial issue. If he were white, he would have still been traded.

Washington: Are you considering a second book on African-American athletes?

Early: I might. It’s just a matter of having enough time. I haven’t, by any means, exhausted my thinking on this topic.

Nancy Fowler is a freelance writer based in St. Louis.

Click here to read The New York Times Book Review.

For a recent university news story, visit http://news.wustl.edu/news/Pages/23078.aspx.

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.