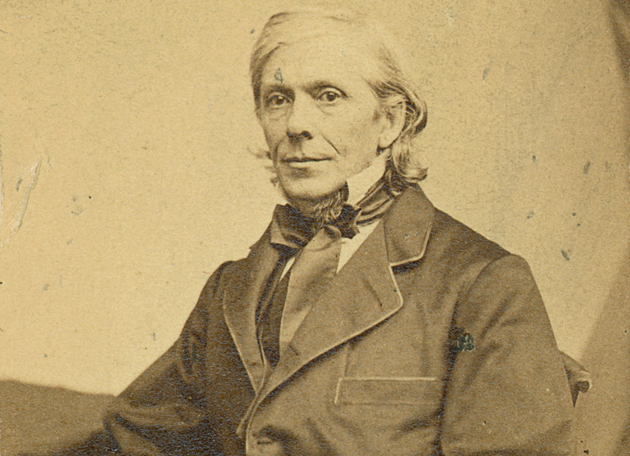

In November 1834, a young Unitarian minister — Rev. William Greenleaf Eliot — arrived in the rowdy frontier town of St. Louis, ready to found a church and help civilize the West. During his remarkable career, which ended with his death in 1887, he built one of the largest congregations in St. Louis; co-founded Washington University, serving as its board president and third chancellor; and played a major role in many civic causes. During the Civil War, he worked tirelessly to save Missouri for the Union and established an important relief organization, the Western Sanitary Commission.

“Why wasn’t this man better known, especially in St. Louis?”

—the Rev. Dr. Earl K. Holt

Fast forward to 1974, when another young Unitarian minister, the Rev. Dr. Earl K. Holt, arrived in St. Louis to become pastor of First Unitarian Church, a successor congregation to the one led by Eliot. In 1975, Holt preached a sermon about Eliot’s life and wondered, as he wrote later, “Why wasn’t this man better known, especially in St. Louis?” In 1983, Holt delivered six lectures, supported by the Minns Committee of Boston, on Eliot’s life and work. Afterward, he turned them into a slender volume — William Greenleaf Eliot: Conservative Radical— published by First Unitarian in 1985. In 2001, Holt left to become pastor of King’s Chapel in Boston and later retired to Phoenix, Ariz., where he is currently interim pastor of Valley Unitarian Universalist Church.

In 2010, two former congregants from St. Louis, Terry Yokota and Dan Franklin, wrote to ask whether he would consider republishing his book through their firm, Village Publishers of Belleville, Ill. The revised edition — with added photos, interesting appendices and an index — came out late in 2011, in time to mark the 200th anniversary of Eliot’s 1811 birth. Recently, Holt sat down for a conversation about the new book and his long-standing interest in William Greenleaf Eliot:

Q: Most people know little about Eliot except that he was the grandfather of poet T.S. Eliot.

A: Even though William Greenleaf Eliot died before T.S. Eliot was born, the younger Eliot talked about how his grandfather was a great influence on him and other family members. I think that is true. One senses that the writings and lives of so many in the family echo him in one way or another. Obviously, Eliot must have been very charismatic. He didn’t look it; he was slight of stature and frail. But he had a great personal impact on the people of his church and others.

Q: What was he like as a person?

A: One thing that surprised me in reading the correspondence he had with his children was how openly affectionate he was. We think of a 19th-century man as very buttoned up, yet so much of him seems very warm and even tender-hearted. At the same time, he was unafraid, courageous — he knew who he was and what he believed in — and was forthright in his human relationships as well as his preaching. I have read a lot of sermons from that era, and his seem notably direct and to the point, not flowery. He had high ideals but was practical in their implementation. He knew what needed to be done.

Q: What were his major accomplishments in St. Louis and nationally?

A: Obviously, he is most remembered for Washington University. By giving this small school the name “Washington” — George Washington was a national hero as well as a personal hero of his — he was seeing it as a national school in its fulfillment. While that wasn’t accomplished in his lifetime, over time the university grew into the school he had envisioned.

He was also involved in building many other institutions in St. Louis. Eliot’s first public role was becoming president of the school board, and he took great pride in passing the first one-tenth of one percent school tax. One day, a scholar and I were at First Unitarian looking at the pictures of its earlier buildings, including the original church on Fourth Street; he pointed to the window of the parish hall and said: “You know, most of the educational and other civic institutions in St. Louis were created in that room.”

Q: What exactly was Eliot’s role in keeping Missouri on the Union side in the Civil War?

A: Well, the major evidence we have are his sermons, which were printed and circulated. Clearly, he was active but most of what he was doing was behind the scenes, and I’m not sure the documentation is there for discovering more. In my own mind, I’m completely convinced that at least once and maybe twice he met with Lincoln, but there’s no record of those meetings that I’ve been able to turn up.

Q: In the title of your book, you call Eliot a “conservative radical.” How was he seen in his time, and how would Unitarians today regard his theology?

A: One interesting thing I learned in writing this book was how heretical Unitarians were considered to be in Eliot’s day. But as time goes by, Eliot talks a lot about feeling more and more on the theologically conservative side of the movement. Today, especially since Unitarianism merged with Universalism in 1961, it has really become a hodgepodge theologically, so that we even have people who call themselves Unitarian Universalist Buddhists or pagans. It’s not recognizable as a tradition rooted in Scripture and the Bible, though a minority of us still thinks that is the root of our movement.

In many respects, I’d like to keep this book in print just for the appendix with the sermon Eliot gave in 1870 called “Christ and Liberty,” in which he lays out the platform of Unitarian Christianity and says he has no fear that the denomination will ever depart from the fundamentals of Christ. We know he is doing that because there had been a controversy in the national conference for some years with the so-called Unity men wanting to reduce the emphasis on Christ as the leader.

Q: On his grave in Bellefontaine Cemetery, Eliot’s epitaph reads: “Looking Unto Jesus.”

A: Exactly. In fact, there’s a touching note in a letter to his friend, the Rev. James Freeman Clarke, in which he says he feels like repeating the name of Christ, over and over. That becomes his whole focus: He really believed he was a servant of Christ, doing his duty as a faithful Christian. I think that this, combined with an authentic personal modesty, led to his instructions that no biography should be written and no eulogy given. His funeral is also fascinating to me because all the pallbearers were men, not of his family, who were named for him. I see that as a symbol of his personal influence.

Q: How do you think he could get through the death of so many children? Of the 14 born to him and his wife, Abby, nine died before reaching adulthood; Mary Institute [now MICDS] is named for his beloved daughter, Mary, who died as a teenager.

A: It’s very touching to read things that he wrote, especially when Mary died. In that time and place, this was not an unusual circumstance; many hymnals in the 19th century have a special section just for funerals of children. But it is still clear that his sense of loss was very, very strong.

Q: What resources did you use in doing your research for this book?

A: The main things were his journals in the Washington University Archives, but I looked in many places. In Missouri and Illinois, I visited the Missouri Historical Society, the State Historical Society and Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville; in Boston, I went to the Athenæum, the Unitarian Archives and the Harvard Divinity School library. I also traveled to theological schools in Berkeley (Calif.) and Chicago.

Q: What do you admire most about Eliot?

A: I’m tempted to say “everything.” He didn’t create it, but he confirmed me in my more traditional Unitarian Christian faith. After I got to know him, I used to go out at least a couple of times a year to his grave at Bellefontaine and talk, even out loud sometimes, about what was going on in the church. That’s a very special place in the world to me. A family at First Unitarian donated a tapestry with his picture incorporated into it, which used to hang on the back wall of the church. I always felt as though he was watching over us.

Candace O’Connor is a freelance writer based in St. Louis.

For more information, visit Village Publishers.

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.