In the gritty St. Louis neighborhood where Clark Porter grew up, life was all about survival. Nobody dreamed of going to college, much less to Washington University. “To say that you were going to get a job? That was like hitting it out of the park, just that alone,” says Porter today.

Many of his friends — poor, unharnessed by education or family — wound up in prison. And that was where Porter spent 15 years of his young adult life after robbing a downtown post office. Then, for reasons that are still hard for him to articulate, he broke the mold. He got out and got serious, working his way through Washington University to a job with the federal probation office downtown — the very same people who had incarcerated him.

“He [Clark] can shatter walls of denial faster than any professional I’ve ever seen.”

— Douglas Burris, chief U.S. probation officer

Today, he is a program support specialist, the only one in the federal system nationwide, fighting to keep some of the toughest repeat offenders out of trouble and on a path to a new life. Excuses? He has used them. Problems? He has faced them. “He can shatter walls of denial faster than any professional I’ve ever seen,” says his boss Douglas Burris, chief U.S. probation officer.

Most days he is too busy to catch his breath, but once in a while it hits him. He might be driving to work when suddenly the majestic Thomas F. Eagleton U.S. Courthouse looms ahead, and he realizes that he — convicted felon Clark Porter — actually works there.

“Sometimes I get these ‘wow’ moments right out of the blue. The whole thing is still hard to imagine,” Porter says. “And I don’t think that will ever stop, because it’s just inconceivable.”

Scrambling up

The sixth of seven children by various fathers, Porter was 4 years old when his mother sent him to live with his grandmother, who had no idea how to quell his anger. When he was 8, she relinquished him to the foster care system, where he tumbled from one home to another. Then at 15, he walked away from it all, living on the streets and doing whatever he had to — shoplifting, petty theft — to get by.

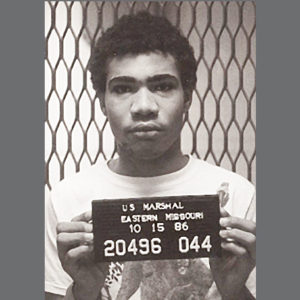

By 17, he was ready for a bigger score, so he and a 30-year-old friend decided to stick up the U.S. Post Office on Fourth Street. Brandishing a sawed-off shotgun, Porter and his friend herded employees into the back, grabbed money from the till, and robbed customers as they came in. Their haul was $632 plus some stamps. Detectives tracked Porter down through the cap he was wearing, and he was sentenced to 35 years in prison.

Inside, he continued to lash out, chiseling knives for violent assaults and ending up in two different “SuperMax” facilities, where he was locked down 22 hours a day. Then, all at once, he was tired of crime. A Greek Orthodox priest befriended him, and he found religion. A correctional officer pestered him to finish his GED. “Once I did that, I said to myself, ‘Man, I can do something,” he recalls.

College and beyond

Released to U.S. Probation in 2001, Porter quickly jumped into recovery: seeking out a therapist to deal with his painful childhood, attending N.A. meetings to keep a minor drug habit in check, working closely with a sympathetic parole officer, scraping up part-time work, and taking classes at Forest Park Community College. An English teacher there, Lori Hirst — wife of Washington University history Professor Derek Hirst — was so impressed by his papers that she brought some to Robert Wiltenburg, dean of University College.

“We were struck by the force and vigor of his writing, as well as his interesting self-perceptions, and we offered him a scholarship.”

— Dean Robert Wiltenburg, PhD

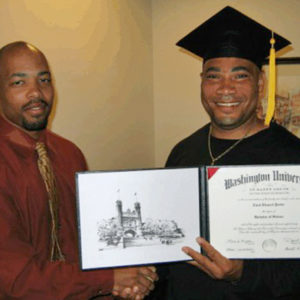

“We were struck by the force and vigor of his writing, as well as his interesting self-perceptions, and we offered him a scholarship,” Wiltenburg says. “We’re happy to have played a role in his education, and we’re proud to have him as our graduate.”

Another “wow” moment happened soon after Porter’s graduation, when an aunt came to pick Porter up. “She is not a person who cusses,” Porter says. “But here we were in her car, and she just turned around and looked at me and said: ‘Why, you son-of-a-xxxx, you just graduated Washington University.”

He found part-time work as a tutor and research assistant, went on to earn a master’s degree in social work from the University of Missouri–St. Louis, and began looking for a career. He dropped off his résumé with Burris, who was intrigued. With the support of colleagues in the U.S. District Court, Eastern District of Missouri — particularly then Chief Judge Carol Jackson — Burris hired Porter. “I have to admit that originally I thought it was crazy to hire an ex-offender who had robbed a post office that we supervised,” Burris says. “But it turned out to be brilliant.”

The federal program today

In the federal probation system, every client is scored with a Risk Prediction Instrument that tabulates such problems as lack of education or family support, mental illness and drug addiction. Of the 94 districts in the country, Porter’s office has the highest-risk caseload, with the most violent repeat offenders. St. Louis has more people under supervision for federal gun crimes than Los Angeles, Chicago or New York City.

Porter and U.S. Probation Officer Lisa White, AB ’95, MSW ’03, a colleague and fellow WUSTL alum, developed an intensive program, Project Re-Direct, targeting a few of the folks with “one foot back in prison,” he says. He helps them with basic needs — a bed, baby stroller, a refrigerator, assistance with a heating bill — so they don’t lose heart and resort to crime. His probation office is the only one in the country with a rented truck to handle the donated items.

“We also get them to take ownership of their problems,” he says. “They will say, ‘You guys put me in this program; you guys charged me.’ I say, ‘No, if you hadn’t been selling drugs, you wouldn’t be here.’ And it’s a little harder for them to say: ‘You don’t understand’ when they’re talking to another ex-con.”

Of the 61 people who have gone through the program to date, fully 40 have made it through school or to a job — a two-thirds success rate in a population that normally has the identical failure rate. And Porter is involved in other programs, too, such as Project EARN, in which he and a team of probation officers, counselors, lawyers and judges help drug-addicted clients lead more productive lives.

Today, people who hear Porter’s story are astonished; this summer, for example, he presented at the Federal Judicial Center’s Chief U.S. Probation and Pretrial Services Officers National Conference. And his story will soon be part of a documentary, which is currently in production. His example has also inspired his own colleagues, who deal with ex-offender clients every day.

“The ‘us’ and ‘them’ mentality has largely disappeared with Clark here,” Burris says. “Now people here see that we’re all part of the community. Now it’s different: It’s ‘us’ and ‘us.’”

Candace O’Connor is an Emmy Award-winning freelance writer based in St. Louis.

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.