“They are plucky fellows and are thoroughly American,” declared the missionary William Whipple from Tabriz, Persia, in August 1891. He was referring to two houseguests, William L. Sachtleben and Thomas G. Allen Jr., who were attempting a historic “round-the-world” journey by bicycle.

While seniors at Washington University, some 15 months prior, the pair had discovered the increasingly popular “safety” pattern. The silent steed boasted two small wheels, the rear one driven by chain and sprocket. With its invitingly low profile, it was rapidly displacing the fleet but precarious “high wheeler,” whose ridership was confined almost entirely to athletic young men.

Truth be told, their brash scheme was not entirely original. A few years earlier, riding an old-fashioned Ordinary, an Anglo-American named Thomas Stevens had covered some 13,500 miles on three continents in the course of three years. Stevens, however, had done little cycling in the foreboding continent of Asia, where few denizens had ever seen a Westerner, let alone a bicycle.

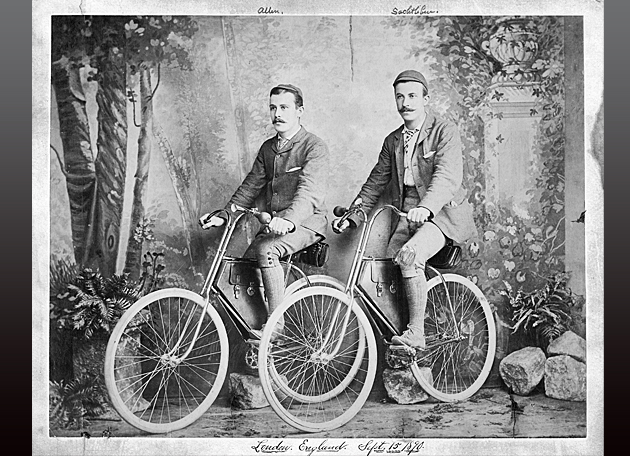

The day after graduation, in June 1890, the men boarded a train to New York City, and thence a steamer to Liverpool, England, where they promptly purchased a pair of Singer safeties, with hard tires. They intended merely to spend the summer tooling around the British Isles. But they enjoyed that experience so much that they resolved to continue pedaling eastward, taking ships only when necessary, until they had completed a global circuit.

Truth be told, their brash scheme was not entirely original. A few years earlier, riding an old-fashioned Ordinary, an Anglo-American named Thomas Stevens had covered some 13,500 miles on three continents in the course of three years. Stevens, however, had done little cycling in the foreboding continent of Asia, where few denizens had ever seen a Westerner, let alone a bicycle.

In London, Allen and Sachtleben declared their intentions to the British press. They acquired new, lighter bicycles, with cushion tires (essentially circular hoses, with greater give). They also purchased the newly introduced Kodak film camera to record their adventures, which they agreed to write up for a popular weekly, the Penny Illustrated Paper.

After crossing France and Italy in the fall of 1890, they settled in Athens to wait out the winter. There, they met an Armenian radical named Serope Gurdjian, a graduate of Bowdoin College. So enrapt were they by his riveting tales of his people’s struggles against the oppressive Ottoman Empire, that they decided, come spring, to pedal 1,000 miles across the heart of Turkey, along the ancient caravan road inhabited largely by nomadic Kurds.

To prepare for the arduous journey — which would limit their recourse to railroads while exposing them to thoroughly foreign languages, cultures and diets — they secured their third set of wheels, British-made Humber bicycles (both still exist, see sidebar). Having clashed with the editor of the Penny Paper, they ceased their correspondence. No matter. They were sufficiently well off that they could resume their journey without sponsorship, and they resolved to write a book about their adventures upon their return (Across Asia on a Bicycle: The Journey of Two American Students from Constantinople to Peking, paperback 2003).

In spring 1891, the two rode across the desolate plains of Anatolia to Ankara, spending their nights at grimy inns. Heading toward the Persian border, at every town along the way, they found themselves besieged by excited locals who demanded an opportunity to interview them and examine their bicycles. At times, they had to evade rocks thrown in their direction, not to mention barking dogs snapping at their heels. On numerous occasions, the local authorities forced them to hire armed guards on horseback, to escort them by day.

Unwilling to confine their exertions to cycling, the two paused to climb Mount Ararat, with the help of hired guides. Reaching its summit on July 4, 1891, they planted an American flag as they jubilantly fired their pistols into the air.

“We have had them as our guests for three weeks … It seems marvelous how they can travel through Turkey and Persia without the languages or guides. They have had to ford rivers, carrying their wheels, and climbing high mountain passes, etc., and live native-like in every place they stop.”

— Reverand William Whipple from Tabriz, Persia

At Tabriz, they lingered long enough for Sachtleben to recover from cholera. “We have had them as our guests for three weeks,” the Reverend Whipple continued, “and have enjoyed talking to them concerning their route from Liverpool [to] here … It seems marvelous how they can travel through Turkey and Persia without the languages or guides. They have had to ford rivers, carrying their wheels, and climbing high mountain passes, etc., and live native-like in every place they stop.”

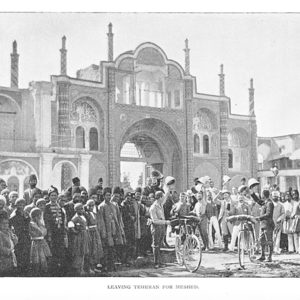

Arriving in Tehran in late August, with temperatures soaring to 120 degrees, they once again suspended their trans-Asiatic journey, to await Russian passports. For the sake of originality, they had ruled out Stevens’ southern route through India, though it was undoubtedly the easiest option. Instead, they decided to head northeast to Turkistan, then across Siberia to Vladivostok.

Six weeks went by, and still they had no papers. Finally, the Russian consulate persuaded the men to continue east across a desert to the holy city of Meshed, where, he assured them, his colleague would fulfill their request. Indeed he did, much to the elation of Allen and Sachtleben. Dashing off again, with the help of a 600-mile lift from the new trans-Caspian railway, the cyclists got as far as Tashkent, before another winter set in.

In spring 1892, they resumed their ride. Nearing Siberia, they changed their plans once again. There was yet another other way to cross Asia, via northern China. Indeed, they had already secured a Chinese passport while in London, with help of a reluctant Robert Todd Lincoln, the American ambassador and the eldest son of the slain president. After receiving assurances from local missionaries that a trek across the Gobi Desert was not necessarily suicidal, they decided that this was indeed the most challenging and appealing route.

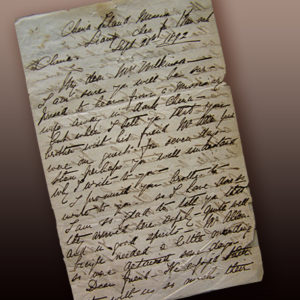

“I am sure you will be surprised to hear from a missionary’s wife away in dark China, but when I tell you that your brother with his friend Mr. Allen [junior] were our guests for seven days — then perhaps you will understand… I am so glad to tell you that they arrived here safely, quite well and in good spirits.”

— Agnes Laughton wrote from Lanzhou, China, to Sachtleben’s sister in Texas, under the dateline of Sept. 20, 1892

Shedding all unnecessary weight, the two emerged from the desert two weeks later, weary but unscathed. After visiting the Great Wall, they reached the city of Lanzhou, where a Scottish missionary family gave them refuge. Mr. Laughton helped to secure telegraph wire to mend Allen’s broken top tube. His wife Agnes, for her part, wrote a reassuring letter to Emma Wilkinson, Sachtleben’s sister in Texas.

“I am sure you will be surprised to hear from a missionary’s wife away in dark China,” Agnes wrote under the dateline of Sept. 20, 1892, “but when I tell you that your brother with his friend Mr. Allen [junior] were our guests for seven days — then perhaps you will understand… I am so glad to tell you that they arrived here safely, quite well and in good spirits. Dear friend — we enjoyed their stay with us so much. Their company was so bright and pleasant. When they left us we missed them so much. Our photos have been taken by your dear brother in various ways. It was so kind of them both. It was a great pleasure for me to attend to some little darning[,] sewing[,] etc. for them. I only wish they could have taken more provisions with them. We tried to make them feel as much at home as possible. We do trust that they may reach home safely.”

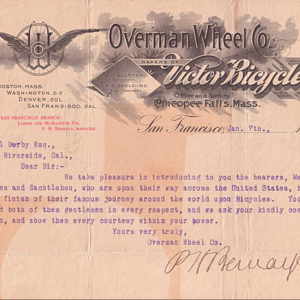

Visiting San Francisco at the close of 1892, the two adventurers became instant celebrities. The great bicycle boom was about to explode, and they had just completed what one journalist pronounced “the greatest journey since Marco Polo.” An agent of the Overman Wheel Company presented them with a pair of brand new Victor pneumatic bicycles, for their final leg across North America.

In June 1893, three years to the day after they had left Washington University, they made their triumphant entry into New York City. A writer for The Wheel, a popular cycling magazine, found them in a content but sober mood. “They say they have wasted three valuable years,” he reported, “but that it will repay them eventually, as they have a stock of health and vitality.”

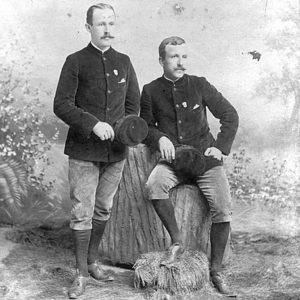

William Sachtelben (1866–1953), of Alton, Ill., would eventually settle in Houston, where he managed the Majestic Theater for many years. Thomas G. Allen Jr. (1868–1954), of Kirkwood, Mo., became a noted engineer.

The two would reunite briefly in 1936, when Allen, who had become a British subject, made a return visit to the United States. In a letter to the Alumni Bulletin, Sachtelben gushed: “I cannot express how deeply my reunion with Tom Allen affected me. It was as if I were given a new lease on life after forty-two years again to be permitted to grasp the hand of the man who so patiently and fearlessly shared all the hardships and dangers of our ride across Asia on bicycles.”

David V. Herlihy is the author of The Lost Cyclist: The Epic Tale of an American Adventurer and His Mysterious Disappearance (Houghton Mifflin, 2010).

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.