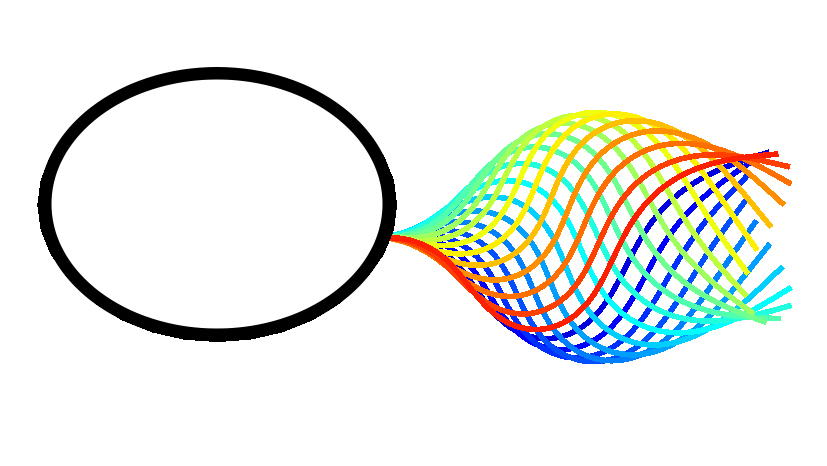

They are the tiny motors present in many of the human body’s most complex systems. Cilia are hair-like structures that oscillate in waves, and are present in the brain, kidneys, lungs and reproductive system. They move liquids such as cerebrospinal fluid and mucus past the cell surface, and throughout the body. Flagella are whip-like structures that steer cells along. Both are of vital importance to human health.

The wavelike motions of flagella have been known since van Leeuwenhoek observed swimming sperm cells and protozoa in the 1600s; how they do it remains much less clear.

“They spontaneously beat,” said Philip Bayly, the Lilyan and E. Lisle Hughes Professor of Mechanical Engineering and chair of the Department of Mechanical Engineering & Materials Science at the School of Engineering & Applied Science at Washington University in St. Louis. “But how they beat is really a mystery.”

A team from Washington University, comprised of engineering faculty and faculty from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, has been awarded a 5-year, $1.25 million grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to study how these tiny organelles actually work. Unlike the oscillations of a heartbeat, which are well-documented and explained, the cyclical behavior cilia and flagella remains an active research area.

“We understand the basics,” Bayly said. “There are motor-proteins that must be responsible for the movement, but why things move back and forth as opposed to just moving in one direction is a mystery. It’s a problem that intrinsically needs an interdisciplinary team to work on it.”

Bayly will be joined in the research by colleagues Mark Meacham, assistant professor of mechanical engineering and material science, and Jin-Yu Shao, associate professor of biomedical engineering, both in the School of Engineering & Applied Science; along with Susan Dutcher, professor of genetics and of cell biology and physiology, and James Fitzpatrick, associate professor of cell biology and physiology and of neuroscience, both at the School of Medicine. Dutcher is acting director of the McDonnell Genome Institute. Fitzpatrick is also director of the Washington University Center for Cellular Imaging.

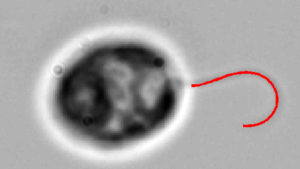

The entire team will examine the movement and mechanics of flagella in a green alga called Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, or Chlamy, an unlikely but nearly perfect research substitute for human cells.

“The flagella of this alga is almost identical to the cilia in the human body,” Bayly said. “It’s like a biological miracle that the same structure that propels these swimming algae lines our airways.” It is also relatively easy to tweak the genetic makeup of Chlamy to affect flagella structure.

The researchers will use a variety of techniques to test and study the algae flagella. High-frequency sound waves will help immobilize the organisms, so the team can alter each cell’s environment and observe individual responses. The researchers believe the observations made during the course of the experiments will also be applicable to cilia in humans, and could lead to a whole host of new discoveries: mechanical and medical.

“As an engineer, I’m fascinated by the idea that if we knew how these cilia worked, you could engineer something that works like them,” Bayly said. “These are tiny (organisms) and they swim autonomously. There’s no nervous system telling them what to do, there’s no computer; they swim automatically. If you can figure out how they do that, I think it would open the door for new types of microscopic machines.

From a disease standpoint, it opens to door to understanding diseases — and maybe treating diseases — where cilia don’t work correctly. That would include some genetic disorders and even COPD.”

Bayly is available for interviews and may be reached at pvb@wustl.edu.

The School of Engineering & Applied Science focuses intellectual efforts through a new convergence paradigm and builds on strengths, particularly as applied to medicine and health, energy and environment, entrepreneurship and security. With 90 tenured/tenure-track and 40 additional full-time faculty, 1,300 undergraduate students, more than 900 graduate students and more than 23,000 alumni, we are working to leverage our partnerships with academic and industry partners — across disciplines and across the world — to contribute to solving the greatest global challenges of the 21st century.

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.