The telegram arrived in the nick of time.

It was April 1942. Months earlier, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had signed Executive Order #9066. Approximately 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry — two-thirds of them American born — were forced from their homes and into internment camps.

Gyo Obata’s family was ordered to the Tanofran detention center in San Bruno, California. But as they prepared to leave, Gyo received word that he’d been admitted to the architecture program at Washington University in St. Louis. He boarded a train that evening.

“If you got an acceptance from a university away from the West Coast, then you could leave California,” Obata says. “I was able to leave the night before my family … was moved into camp.”

Rebecca Copeland, chair of the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures in Arts & Sciences, explains that “many university chancellors, presidents and registrars were deeply disturbed by internment. They were concerned about how it would affect all these bright young minds.”

Working under the auspices of the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council, administrators established guidelines to assist students in transferring from the West Coast to schools outside the “forbidden zones.” Criteria included the following: U.S. citizenship, academic achievement, compatible personalities and funds to cover their studies.

At Washington University, Chancellor George R. Throop welcomed about 30 evacuees. Among them were celebrated architects Richard Henmi and George Matsumoto, and sociologist Setsuko Matsunaga Nishi.

“The attitude of the University is that these students, if American citizens, have exactly the same rights as other students who desire to register in the University,” Throop wrote at the time. He later added that the university would be “glad to receive them on exactly the same basis as other students, and to do all we can for them after their arrival.”

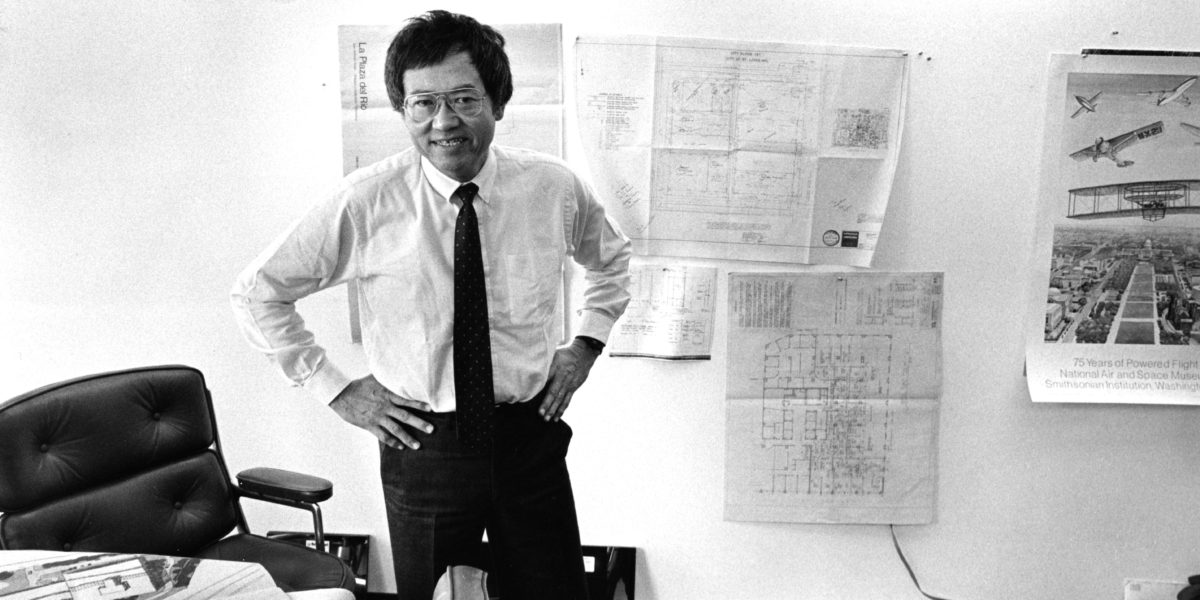

Obata, who graduated in 1945, would emerge as one of the most influential architects of his generation. In 1955, after stints with SOM in Chicago and with World Trade Center designer Minoru Yamasaki, he teamed up with fellow Washington University alumni George Hellmuth and George Kassabaum to found St. Louis–based HOK.

“It was tiny,” Obata says of the firm’s early days, “the three of us and half a dozen other draftsmen. But we wanted to work on many different types of projects. We wanted a practice that was very broad.”

Today, HOK employs more than 1,700 people in 23 offices worldwide, placing it among the world’s largest firms. Obata’s design credits range from the Saint Louis Science Center’s James S. McDonnell Planetarium to the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.

“One lesson is how quickly principles can be overtaken by fear,” says John Inazu, the Sally D. Danforth Distinguished Professor of Law & Religion, whose father was born in Camp Manzanar. “We saw this during World War II, we saw this after 9/11, and in some ways we’re seeing it again today.

“All our talk about civil liberties, the constitution and democracy is only as good as we live it out to be.”

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.