While Washington University was founded in St. Louis — and has made the city its home for 167 years — its faculty, students and staff routinely travel around the world to conduct research, study and strengthen relationships with partner institutions. When they’re on the road, the university stands at the ready to assist should difficulties arise. The COVID-19 pandemic was a difficulty of epic proportion, and it presented an enormous challenge.

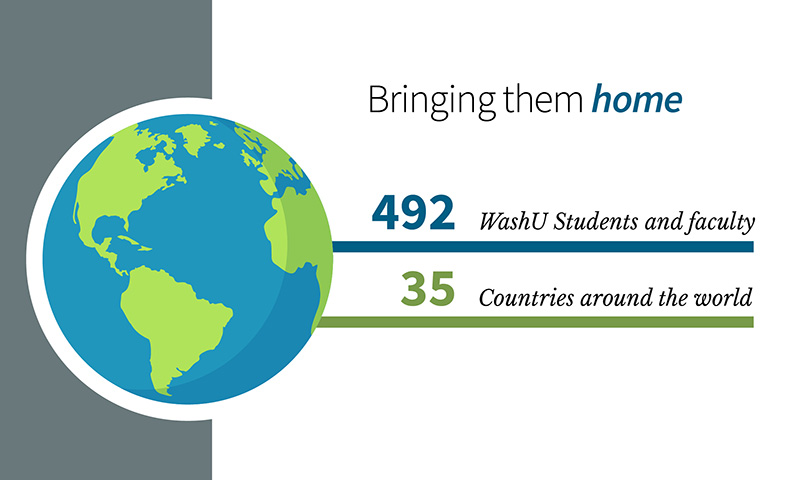

From late February and for the next several weeks, a team from Washington University worked tirelessly to bring nearly 500 WashU community members home from 35 different countries as border lockdowns, travel restrictions and rising infection rates rocked the globe.

“It’s become clearer and clearer what a whirlwind it was,” said Catherine Dalton, global travel safety manager. “I think when you’re in it, you’re just trying to get things done and figure it out. Looking back, it’s just really incredible what we were able to accomplish.”

Monitoring the risk, making tough calls

The university’s International Travel Oversight Committee (ITOC) was established to keep WashU overseas travelers safe and secure when they are away from St. Louis. This group of university leaders from across units meets regularly, and routinely monitors situations around the world in an effort to assess every possible emergency or risk. ITOC keeps current university-related travel information and itineraries on hand from the MyTrips International Travel Registry, and, when necessary, communicates with and connects WashU travelers to International SOS, to provide them with the medical or travel assistance they might require.

The university recognized a very real public health emergency was percolating in China on Jan. 22. That’s when the World Health Organization scheduled a meeting to discuss the outbreak and spread of a novel coronavirus in Wuhan. When the Centers for Disease Control and the Department of State upgraded their travel notices to China the following week, the university acted quickly. ITOC issued a travel suspension for mainland China on Jan. 29, canceling student programs there before they started for the spring semester.

“We recognized that we were very much at a tipping point in various parts of the world, and made sure that we were monitoring every possible source,” said Amy Suelzer, director of overseas programs. “We were working with guidance from infectious disease experts at the School of Medicine, the Department of State, and Centers for Disease Control, as well as accessing International SOS to pull vast amounts of information to inform our decision making. It was very, very much a collective effort.”

In the meantime, ITOC continued to monitor the situation and advise students and faculty who had questions about travel safety on an individual basis. The following month, on Feb. 25, as the coronavirus began to spread outside China and into southeastern Asia, ITOC issued a travel suspension for South Korea, again early enough to cancel study-abroad programs there.

Just three days later, it became clear just how dire the situation had become in Italy. On Feb. 28, the university decided to recall all students and faculty from the country. The cascade effect continued: March 11, recall notices went out to everyone in Europe, the United Kingdom and Ireland. On March 13, the third and final university recall went out: everyone abroad needed to come home, quickly. And the university began a Herculean logistical effort to do just that.

“This was unprecedented,” said Suelzer. “I’ve been working in study abroad since 1999, we’ve been through SARS, we’ve been through MERS, we’ve been through H1N1. I’ve never seen anything like this in terms of scope. While it was daunting, it was very clear we had strong support from the university and our close partnerships abroad. I don’t think at any point we thought the task was unmanageable because we had such strong support.”

Same page, same goal

While traveler recall decisions were guided by the ITOC, the committee had a wide range of university partners collaborating with it in partnership. Representatives from Insurance & Risk Management, the Office of General Counsel, Emergency Management, Overseas Programs, and the School of Medicine all serve on the ITOC’s executive board, and each provided invaluable insight as the university embarked on next steps. School deans and the Chancellor’s Office were also consulted and involved.

“The fact that we were all on the same page, with the same goal for the response was really key,” said Dalton. “There really was some nimble decision making by the group, trusting to work with each other in coordination, and recognizing that the ultimate objective was getting everyone home quickly and safely.”

The first step to achieve that objective began with the initial communication to travelers in the field. Travelers were notified via email and text about the recalls. Undergraduate parents received the same outreach as their children, to ensure families were on the same page with next steps and protocol. It was difficult news to break. The staffs of Overseas Programs office, Olin Global Programs, and the Sam Fox School were on the front lines of the effort, providing support for the communications to parents and students, fielding emails and calls, and sharing updates from programs for those who had been recalled.

“The thing that was hardest was the disappointment,” said Suelzer. “These students and families had been looking forward to this experience for nine or more months—the students had applied in May of the previous year for spring Study Abroad. In the end, there was definitely appreciation for what the university was able to do, and the timeline of the decisions made. We were fortunate that we did manage to make these decisions in such a way that it got most of our students out ahead of the worst.”

“Our message evolved from our first recall with the students who were in Italy,” said Liz Shabani, director of global programs at Olin Business School. “After working with them, we could anticipate what the big questions would be for the next rounds of recalls. We knew we could help by being concise and direct, and let them know they were not returning, as opposed to this being a temporary leave.”

From there, the university worked with International SOS to give students information about changing flights, and what they might expect when they got to the airport. Some students were put directly in touch with Washington University’s travel agency to for assistance in booking flights if they hadn’t already purchased tickets. And above all, it was made clear that the university would assist and support getting them home as soon and as safely as possible.

“We really wanted to try to eliminate any barriers to doing what we had asked them to do,” said Suelzer.

Further complicating the situation, all of the outreach and arrangements were being made at a time when things were equally uncertain back in St. Louis. The three recalls were issued just prior to the university deciding to keep students at home after spring break, and continue the remainder of the semester online. The campus — normally a haven and safety net — was now an unknown zone.

“We were working in a changing environment considering what was happening on campus,” said Shabani. “Something that normally might have been an easy answer—even that was evolving. It involved what was happening back here in St. Louis, and not just the abroad experience.”

And at times, the effort required even heavier lifting requiring collaborative ingenuity and a willingness to answer the call, no matter the time of day or night.

“We had one specific situation where we had a post-doc and an undergraduate student trapped in Peru because they closed the borders, and I needed to get into contact with someone who might be able to get our folks back on a repatriation flight,” said Dalton. “We got news of this at 10pm on a Saturday night. I emailed someone in Government Affairs, explaining the situation and asking for them to give me a call when they had the chance, thinking they wouldn’t see it until Sunday morning. Just minutes later, this team member called me and said ‘Let me start making some calls.’”

The university’s intervention ended up involving the U.S. and Peruvian governments, elected officials, and International SOS. The effort paid off; the WashU students made the first repatriation flight out of Cusco.

Upon return

The university support effort didn’t conclude once everyone eventually made it back to the United States. The students and faculty were returning to a drastically different place than the one they had left. Medical protocol—including self-isolation for those returning from hot zones—needed to be worked through, and a plethora of questions still needed answers. Many took innovation, creativity and case-by-case care to sort out.

“The Habif Health and Wellness Center and our infectious disease experts were helping us to guide recommendations for our students upon return,” said Shabani. “Once they got back, we had lots of students asking questions, including ‘What is it going to look like when I get back?’ ‘Do I need to get an apartment by myself?’ ‘How am I going to get food?’ or ‘My family is immune-compromised, what if I can’t return home?’ Those were the types of questions we were looking to answer quickly to be of assistance to our students.”

Much like the process required to secure their safe returns, getting international travelers truly settled and squared away once back in the U.S.—especially students—took a collaborative, whole-team approach to accomplish.

“We worked with Residential Life to make sure if they needed a place to stay in the interim they could, and for students who had questions about their health or risk of exposure, we got them connected to Habif,” said Dalton. “It was really taking the traveler all the way from ‘It’s time to come home, here’s what that means for you,’ to ‘Here’s how the university can support you in doing so, and afterwards.’”

More work to do, lessons learned

“I still can’t get over what people at Washington University are willing and able to do for each other without a second thought.”

Catherine Dalton

While the team’s initial mission—getting all members of the WashU abroad community home safe—was a success, it’s hardly the end of the effort for those who worked so hard to bring them back. The issues of academic credit and reimbursements are still being sorted out. This too has taken some creative engineering, with some students dropped into WashU online and mini-courses once they returned home as well as completing the work they started abroad through distance learning.

“It’s still ongoing in some ways,” said Suelzer. “This is in phases: first we got them home safely, then we need to figure out the academics, and the finances. It’s been an extended process and there’s still a lot of work happening to make sure that the students we recalled can successfully complete the semester, and that all the academic units are aware of everything these students have been through. That will be going on for a while.”

Meanwhile, the International Travel Oversight Committee plans extensive debriefs and workshopping to further analyze the university’s repatriation response and make suggested improvements, which will further inform traveler safety and security moving forward.

Dalton, who stepped into her role with ITOC and global travel safety from Emergency Management just six months ago, says the success of this mission was less about a formal plan, and much more about the team behind it.

“I still can’t get over what people at Washington University are willing and able to do for each other without a second thought,” said Dalton. “To me, the main takeaway isn’t about process, it’s that we’ve got really good people who care about our folks.”

WashU Response to COVID-19

Visit coronavirus.wustl.edu for the latest information about WashU updates and policies. See all stories related to COVID-19.

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.