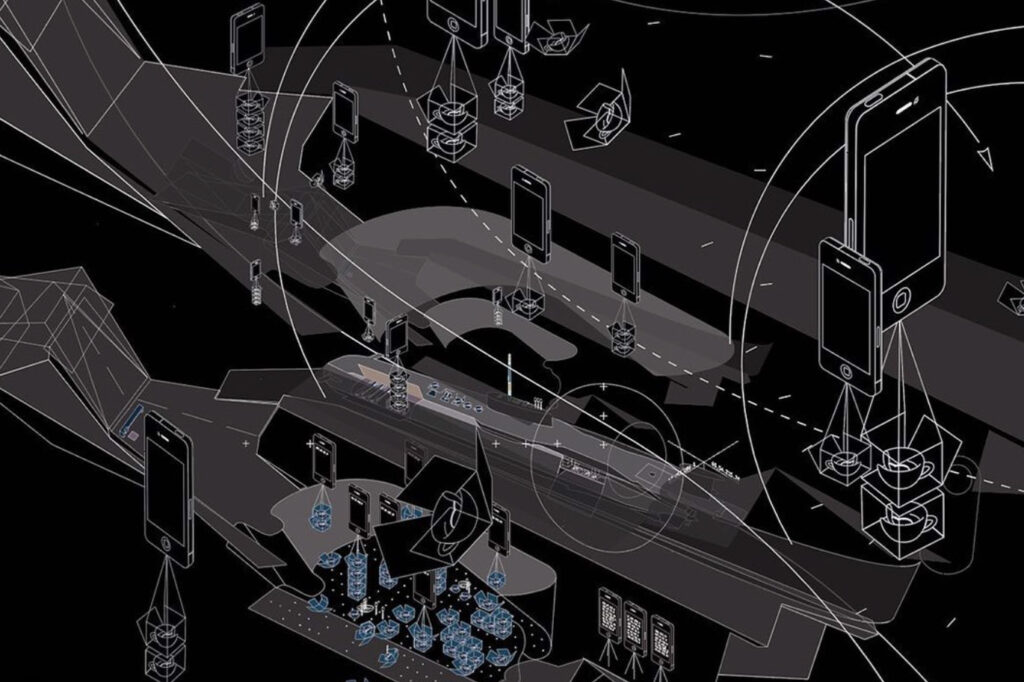

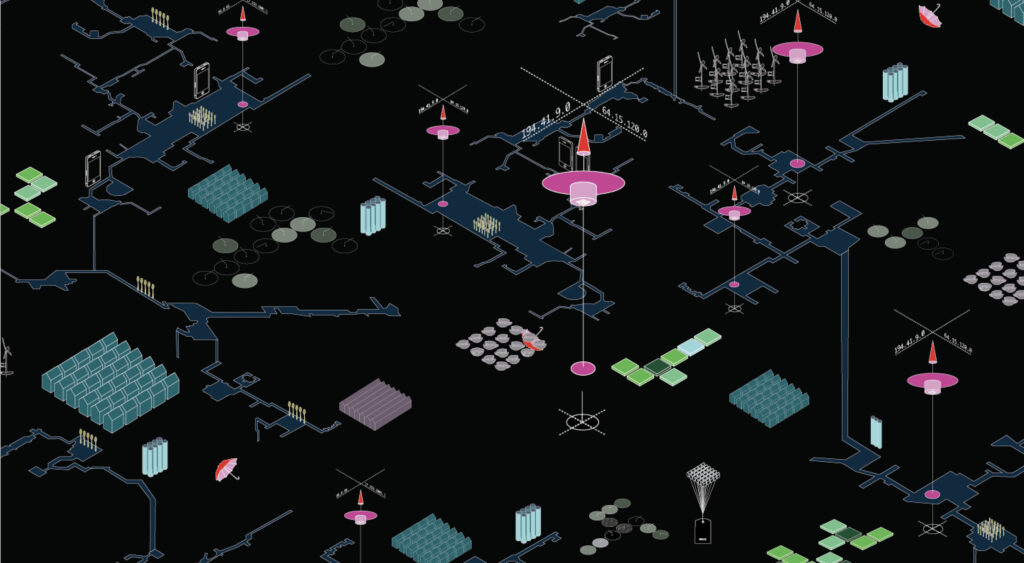

Pink umbrellas tumble on hidden winds. IP addresses cross like city streets. Bright islands of community float like balloons, tethered to gray infrastructural networks.

In her wall-sized drawing “Confronting Urbanization: The Interactive Tissue of Urban Life Pro[log]ue,” Petra Kempf, assistant professor of architecture and urban design in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis, combines copious data and mischievous symbolism to explore how smartphones, online commerce and global connectivity are reshaping the urban terrain.

Some two years in the making, “Confronting Urbanization” recently was featured in the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale, one of the world’s premiere architectural showcases, as part of the exhibition “Time Space Existence,” organized by the European Cultural Center. In this Q&A, Kempf discusses her work, the nature of place and the importance of play.

You draw a fundamental distinction between space and place. How do you define those terms?

Space can be measured. Place is something that people construct through collective interaction. It’s not physical — it’s a creation. Place is something that is always unfolding but that doesn’t actually exist.

In medieval times, maps reflected a sense of place that was very tied to local knowledge. There was an aura or atmosphere that reflected local existence and common understandings of the world. During the Enlightenment, the idea of space became more important, and today, if you look at Google maps, everything is precisely measured. But how do you measure an atmosphere?

So place may coincide with location, but the key components are cultural and interpersonal?

Yes. I’d say that place unfolds when people are interacting with one another.

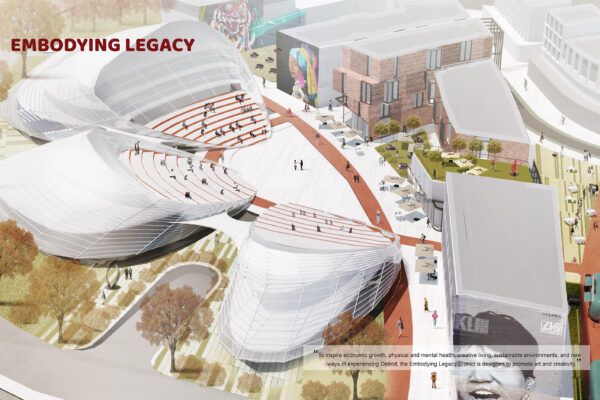

In Venice, I moderated a panel on “Architecture for the People.” One architect talked about infiltrating an inner urban block with a new school, because the school would become a platform for creating interaction — between kids but also with people living on the block. I thought that was a beautiful example of making place.

Another person, who works with the U.N., talked about how migrant camps are often defined in technical terms, but don’t really consider the cultures and identities that people bring with them.

One sometimes hears the phrase “placemaking” in the context of commercial development. But it sounds like you’re after something more ambitious.

Personally, when architects talk about placemaking, I’m always suspicious.

Bernard Tschumi, who was dean of architecture when I was at Columbia, used to say that you can build a kitchen, but people will decide if they’re going to cook there or not. For me that was very revealing. As an architect, you can create a building and hope for a program, but in the end, it’s the people who’ll decide.

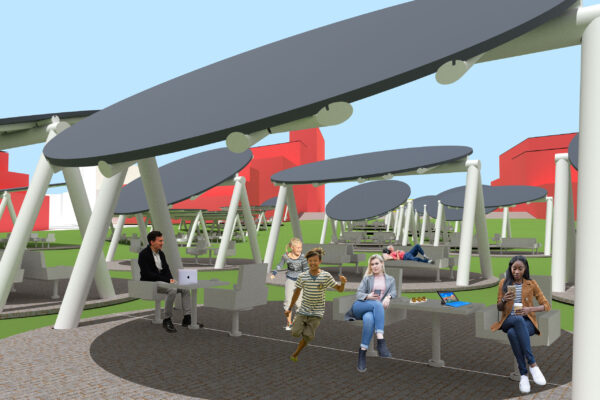

That’s a humbling observation. For practicing architects, what are the implications of prioritizing place over space?

In my studios and seminars, I’m constantly talking about reuse and adaption. I tell my students, you cannot build a project that cannot be changed, because your project is always changing, and your project will never be done. You have to allow for this change to happen. You cannot build a building that is only for this one use.

I never give students a program. I say, ‘Here’s your site and here are the issues you’re confronting.’ [The point] is to look at a neighborhood, and the larger configuration of the city, and the people who are living there. What does it mean to bring something into that neighborhood? How would you go about it? Where would you actually start?

Right now, one of my students is looking into how an empty shopping mall might be adapted for refugees. Could it become the anchor for a new community? I don’t know, but he’s willing to take the risk, which I really applaud.

How does your conception of place relate to the virtual world?

They’re no longer distinguishable. One can’t say, ‘There’s a virtual life and then there’s a physical life.’ It’s all one. Right now, we’re in different buildings but talking [on Zoom] as if we were sitting together at a table. We don’t think twice about it. And while I’m talking to you, there are other messages coming in. There’s no separation anymore.

In “You Are The City” (2009), you argued that we all interpret the city through our own experience of it. Two people living in the same town, or even on the same block, might inhabit very different personal maps. Is there a danger, as place becomes more virtual, that our paths further diverge?

I use the word urbanite, rather than citizen, because I think we’ve forgotten how to be citizens. We’re so entrenched in our own little worlds, revolving around our own needs, our own social media and shopping carts, that we’ve forgotten how to think about the other. We need to figure out how to live together again.

Hannah Arendt described the public realm as a table that both separates and brings people together. I think we all need to get back to that table. That’s why, in my studios, we don’t just pin up boards. Whether you’re a student or a professor, we all sit together.

The umbrella is a recurring motif in your work. What does the umbrella symbolize?

The umbrella is the new urban citizen. It’s about making society more open, because right now, society is too closed. It’s also a symbol of protection. During the Hong Kong democracy protests, demonstrators used umbrellas to shield themselves from tear gas.

And yet your rendering of the umbrella feels almost whimsical. Why is that?

The work that I’m doing can be pretty heavy. I’m very troubled by the world we’re in. There are stressors everywhere: migration, education, health care, housing, energy production, food production… It’s all unsustainable. We need new configurations and new ways of living.

But I also need to draw viewers in, right? These drawings may look light, or cute, or funny. But they’re really not funny at all.

“Time Space Existence” was on view May 22 through Nov. 21 at the Palazzo Mora, the Palazzo Bembo and the Giardini della Marinaressa in Venice, Italy. The exhibition also featured work by Patterhn Ives, the St. Louis-based architecture firm founded by Anna Ives and alumni Eric Hoffman and Tony Patterson, all of whom have taught at the Sam Fox School.

For more information about the exhibition, visit timespaceexistence.com. For more information about Kempf’s work, visit confronting-urbanization.net.

.

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.