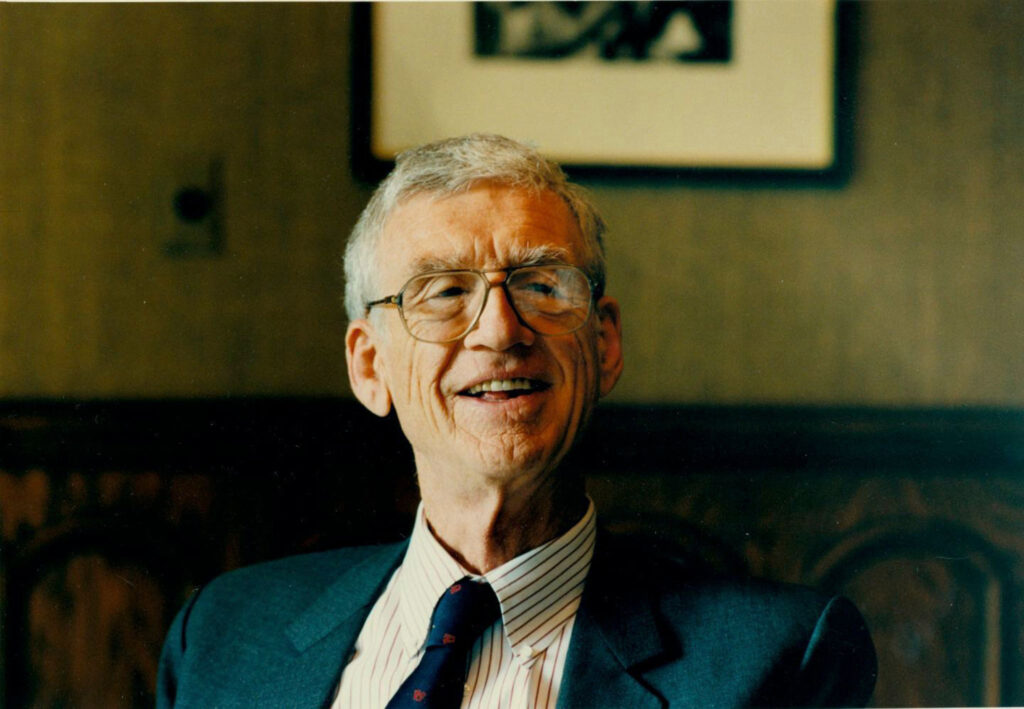

William H. Danforth, who died Sept. 16 at 94 years old, was a physician and educator; a man free of pretensions and constitutionally humble yet dignified and patrician in bearing; a family man, a philanthropist, and an heir to great wealth that over time was spent not in the pursuit of luxury and escape but invested in projects meant to improve the lot of us all.

As a mutual friend once said, there are lots of kindly encomiums for persons of distinction: brilliant, wonderful, generous and so on. But it is a rare person who can be described as great.

Dr. Danforth was such a person. He was great, truly great.

Taking scissors to impossible

Born April 10, 1926, Dr. Danforth — called Bill — was the oldest of Dorothy Claggett Danforth and Donald Danforth Sr.’s four children. He was two years older than his brother, Donald Jr., called Donnie; six years older than his sister, Dorothy Miller, called Dotty; and ten years older than John C. Danforth, called Jack.

Bill was the namesake of his grandfather, the entrepreneur and industrialist William Henry Danforth, who in 1894 established the Purina Mills animal feed business in St. Louis. In the mid-20th century, under Donald’s stewardship, Purina would grow into a commercial powerhouse, a civic institution and a major economic engine.

In 1927, with wealth derived from Ralston Purina, the elder William H. Danforth established the Danforth Foundation. By the time it liquidated holdings in 2011, the foundation had given more than $1 billion to various worthy programs. Just as importantly, the foundation provided progressive leadership and exerted a steadying, mature and disciplined influence on regional growth and development.

William Danforth loomed large in his grandson’s life. When Bill was 12, his grandfather took scissors in hand and snipped the word impossible from his grandchildren’s dictionary. This remarkable vandalism made a vivid impression but also underlined a code of behavior built on hard work, lofty values and optimistic self-assurance.

It was a happy and accomplished family. “When I got older, I liked to talk to Jack and argue politics,” Dr. Danforth once told me, adding that he and Dotty also were close. “Jack and Donnie were close; both Jack and I thought Don was great. Of all of us, Don was the funniest.”

Donnie — who died in 2001 – would become executive vice president at Ralston Purina. He also founded and served as president of Danforth Agri Resources Inc., and Kennelwood, the pet resort. Dotty would become an accomplished horsewoman, though she generally kept out of the public eye, except for the year she reigned as the Veiled Prophet’s queen of love and beauty. She died in 2016.

Jack would become a lawyer, a diplomat and ambassador, an Episcopal priest, and a Republican politician, serving both as Attorney General of the State of Missouri and for three terms as U.S. Senator from Missouri. He is a partner in the Dowd Bennett law firm in Clayton.

Real science

Dr. Danforth said that, growing up, his parents placed on their children neither particular demands nor the burdens of some grand legacy. There were, however, his grandfather’s high expectations to be considered. Dr. Danforth embraced them.

Wars and rumors of wars were facts of life when young Bill Danforth graduated from St. Louis Country Day School, now MICDS. He proceeded to 16 months of Navy training at Westminster College in Fulton, Mo, followed by Princeton, from which he received his bachelor’s degree. Next came Harvard Medical School, though academics were interrupted by Navy service during the Korean War.

Finishing his tour, Danforth returned to St. Louis and specialized in cardiology at Washington University School of Medicine. While a resident, he also worked at the Veterans Administration’s John Cochran Hospital on North Grand Boulevard.

But life took another turn when Danforth was introduced to Carl Cori, chair of biological chemistry, and his wife, professor Gerty Cori. In 1947, Gerty had become just the third woman to win the Nobel Prize in Science and the first to win, together with her husband, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Dr. Danforth continued practicing medicine while working with the Coris but the research he conducted in their lab would have enormous impact on his professional and intellectual development.

“That’s where I learned about real science,” he told me.

A similar humility and openness to experience characterized Dr. Danforth’s approach to education. “I was sort of a typical college student,” he would later observe in an interview with Sondra Schlesinger, professor emeritus of molecular microbiology.

“I was absolutely bowled over by new ideas, things I’d never thought of, learning things,” Dr. Danforth told Schlesinger. “I remember exactly where I was when a fellow student told me that in history things were related, music and the way people were thinking and literature and politics and all these things were related. I never thought of that before.

“It was the most astounding thing I’d ever heard … and I was just bowled over.”

Calm rationality

In the 1960s, officials at Barnes Hospital and WashU School of Medicine grew concerned that operating separately might diminish the strengths of both. The idea of merging was raised. But which institution should take the lead? Discussions grew contentious.

Dr. Danforth emerged as a key facilitator, steady negotiator and source of calm rationality. Outside consultants recommended unification of hospital and school and the establishment of a new position, vice chancellor for medical affairs, who would report to both. Agreement was reached.

Venerated physician Carl Moore agreed to take the job, but for one year only. When he stepped down, in 1965, Dr. Danforth stepped in from the wings, and held the position for six productive years.

During Danforth’s tenure, some officials began arguing that the medical center should relocate, citing fears about safety and middle-class migration. Dr. Danforth opposed the move, both for its gigantic costs and for the negative effects it would have on the city and its diverse patient population.

When it came to a vote, Danforth’s position carried the day. The medical center remained on Kingshighway, a major civic and urban asset and one of the spark plugs for activating, stabilizing and rebuilding the Central West End.

Go west young man

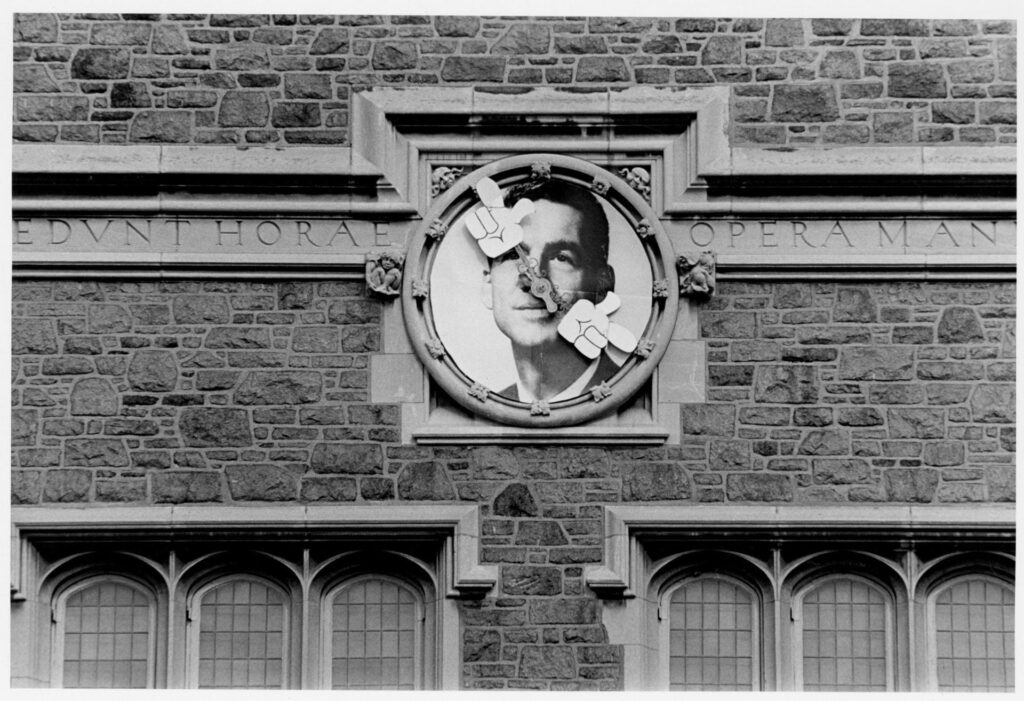

In 1971, Dr. Danforth left Euclid Avenue and headed west to WashU’s Hilltop Campus (now called the Danforth Campus) as the university’s 13th chancellor. Ascending to his office in Brookings Hall, trouble met him practically at the door.

Money was — and is — always a problem for private educational institutions. But under Danforth, the need for assiduous fundraising was a fact faced head on. And when necessary, Danforth money played an enormous role in keeping the going steady.

Nevertheless, when Danforth arrived, it was clear the university was in serious, perilous financial trouble. A $15 million Ford Foundation grant ($3 million a year for five years) had been spent. Wary donors had ceased or pulled back giving. Thankfully, the Danforth Foundation stepped in once again, putting the university, at least temporarily, on an even financial keel. The development office instituted new fund-raising efforts, descendants of which continue today.

But money was only one difficulty. Another was growing pains.

A century after its founding — in 1853 by the Reverend William Greenleaf Eliot, a progressive Unitarian minister, and Wayman Crow, a wealthy St. Louis merchant — WashU was rolling from streetcar college to international status. With prestige came ambitious, outspoken students and faculty. Civil rights and opposition to the Vietnam War had increasingly captured campus attention. A frisson of change and growth was in the air.

In 1970, when a student had torched the ROTC building at the western end of the campus, WashU had felt extremes of blistering scorn and adulation. Yelling and heckling had accompanied a 1967 lecture by Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey. When President Richard Nixon staffer Patrick Buchanan, who once wrote editorials for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, returned to town to talk to students, many regarded him as a monster.

Danforth named this time “the radical period.” For some young men and women, campus life was pretty much as it had always been; hippies and protestors were merely distractions. But for the politically engaged and enraged, protest was why they came to school.

Leadership shoals

By 1976, the commotion had calmed. Nixon’s inauguration in 1973 had been a watershed moment, but Nixon was soon on his way home. Rage was tempered, fires were extinguished, tempers began to cool.

Through it all, Dr. Danforth remained a thoughtful man of rectitude, modesty and generosity, with a deep and visceral understanding of the Ethic of Reciprocity: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

In one of our last conversations, Dr. Danforth told me that he had no idea of the source of his leadership abilities. Certainly some ideas were inculcated early on, at 17 Brentmoor Park in Clayton, where he and his siblings were reared. He also picked up a quirky sense of what works while serving in the Navy.

“I was a medical officer in succession on five destroyers,” he said. “I learned a lot about management on those ships.” Though they looked identical, each had a way of taking on the character of her captain. “One was very nice, read Thomas Aquinas … The crew and officers loved him. The ship was not well run.

“Then there was a drunk ship. The captain was a drunk. There were more cases of drunkenness than sailors. That ship ran well.”

In other words, appearances and perceived behaviors can indeed be deceiving.

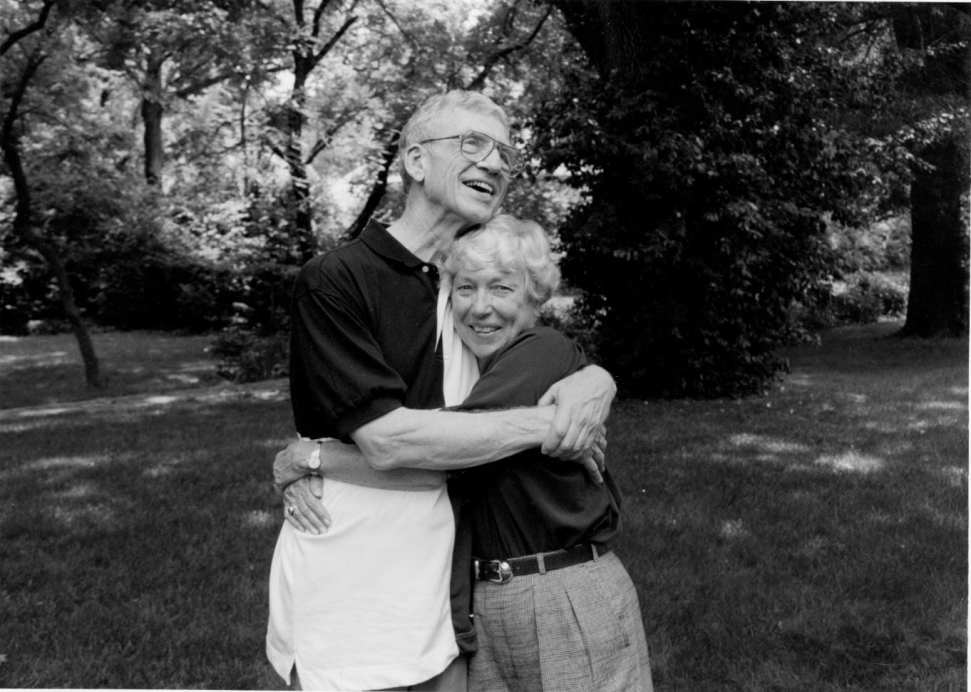

There was another source for his ability to navigate leadership shoals, and that was the support of his wife, the late Elizabeth “Ibby” Danforth. The couple was married in 1950 in St. John’s Methodist Church in Holy Corners on Washington Avenue and Kingshighway. Ibby, too, became an active participant in the life of the university and the community.

“It was a very lucky marriage,” Dr. Danforth said. Luck perhaps, but more likely it was love. Whatever it was, it was sweet, and backed with generosity. “She got up when I came home from the hospital and we had dinner together, no matter what time it was.”

Story time

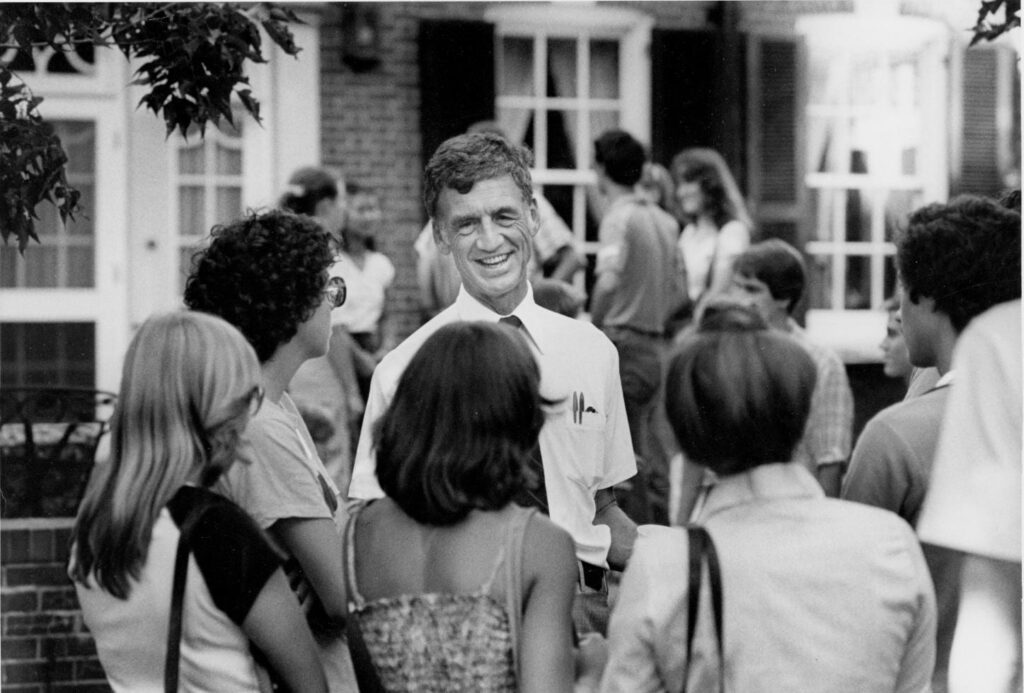

For Dr. Danforth, leadership included understanding the psyches of undergraduates. And so was born story time, his tradition of reading to students in the dormitories.

To understand story time, you have to travel back to 17 Brentmoor Park. When the Danforth children were very young, their grandmother, Adda Bush Danforth, engaged them with bedtime stories. This cemented an influential bond, one that Dr. Danforth sought to establish with other young men and women fresh and far from home.

The literary fare was not “Goodnight Moon” or “Green Eggs and Ham”; rather it leaned to the hilarious and playfully sophisticated stories of the great American humorist James Thurber. Students loved it. The gesture was pure Dr. Danforth: a mix of service, energy and warmth.

Where did the energy come from? Dr. Danforth was not a grind nor some frazzled workaholic. He was driven, however, to succeed in the way his family had succeeded over the generations: with hard, honest work. Work was the generator of educational innovation, of expanding equality, and of sweeping social change.

Moving forward

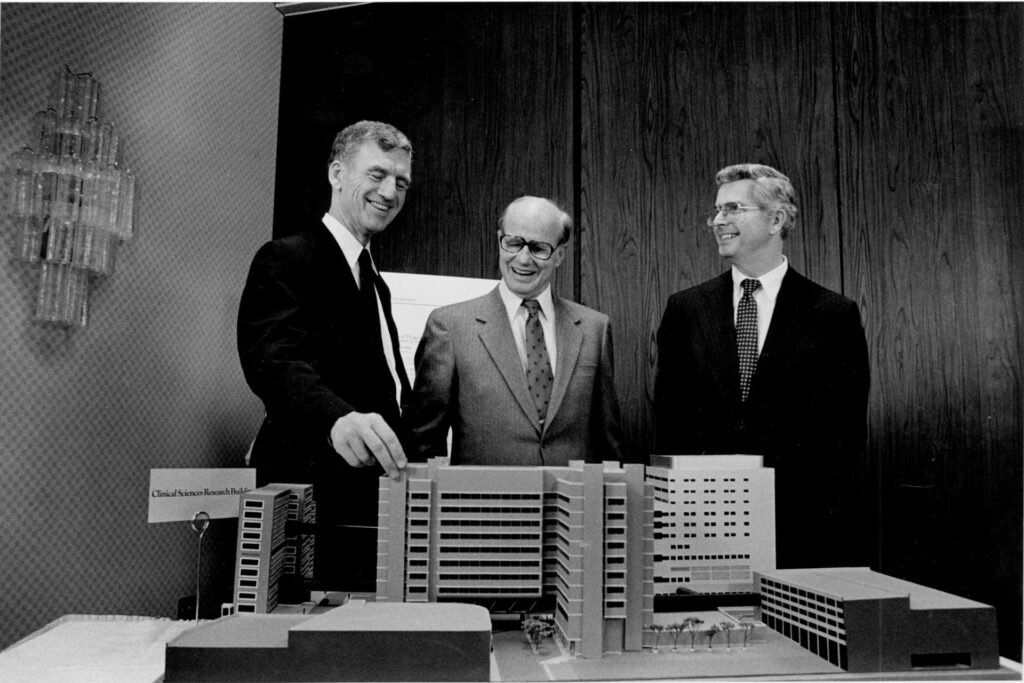

Dr. Danforth retired as chancellor in 1995. Three years later, he joined forces with several colleagues and a large corporation to plan and develop a major new scientific facility. Its purpose would be nothing less than leveraging St. Louis’ strength in biotech and agriculture to eliminate world hunger by developing nutritious, disease- and pest-resistant crops.

The Donald Danforth Plant Science Center, named for Bill’s father, opened in 2001. Now one of the nation’s most technically advanced bioscience facilities, it sits at the heart of a growing Bio Research & Development Growth Park.

In recent years, Dr. Danforth found getting around more difficult, but get around he did, especially for weddings, birthdays and state occasions such as commencements. The university remained a constant part of his life.

At Washington University, Dr. Danforth found not only a challenging environment that would define his career, but also emotional nourishment, constant intellectual stimulation and a profound sense of accomplishment.

In turn, the institution was rewarded by having this exceptional man— this great man — in its midst, a man who stood tall because he was tall, not because he set out to be tall or proclaimed his stature as tall, but because he was tall, and exceptional.

Modesty would have prevented Dr. William Henry Danforth from proclaiming the words that follow. It is not far-fetched, however, to imagine that in contemplative moments he may have said or thought something similar to this, ideas expressed by the 18th century Quaker missionary Etienne de Grellet:

“I shall pass through this world but once.

If therefore, there be any kindness I can show,

or any good thing I can do, let me do it now:

let me not defer or neglect it, for I shall not pass this way again.”

Robert W. Duffy is a Washington University alumnus and longtime adjunct lecturer who has taught in the College of Arts & Sciences and the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts. For more than three decades, he served as a writer, critic and editor at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, then helped to found the St. Louis Beacon, which later merged with St. Louis Public Radio.