A few weeks ago, Sylvester Stallone called Donald Trump with a suggestion: why not grant a posthumous pardon to Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight champion? Given the left-field nature of the idea, there’s a good chance the president may actually go through with it.

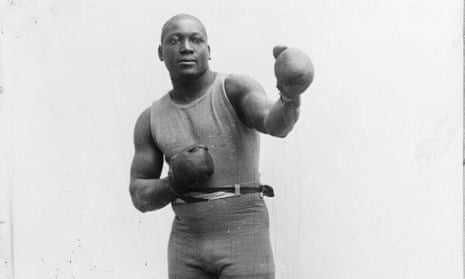

Johnson reigned from 1908-1915, though in the opinion of many boxing experts, he was the best heavyweight in the world for a much longer period. And as documentarian Ken Burns says in his 2004 film, Unforgivable Blackness: “For more than 13 years, Jack Johnson was the most famous and the most notorious African American on Earth.”

Johnson was born in 1878 – or some time around then, there are no surviving records – and grew up in Galveston, Texas, a town, for the time and place at least, relaxed on racial matters. He played with white kids, unaware of the restrictions he would face in the outside world as he grew older. It’s a testament to his strength of will that when he was confronted by those boundaries in later life, he simply ignored them.

When Johnson became rich enough to afford automobiles, he raced them down public streets, and when stopped by white policemen, whipped out some bills from his wallet and told them to “keep the change.” According to a story which has never been verified, Henry Ford gave Johnson a new car every year, assuming that when he was pulled over for speeding, a photo of a grinning Johnson beside his shiny new Ford would appear in newspapers across the country.

It was the same story in the ring. He mocked and taunted his white opponents, derided his black competitors, made his own deals without white managers, flaunted his success in public, and, most shocking of all to both blacks and whites, romanced and married white women, abusing at least one of them.

Though Johnson was undeniably brilliant in the ring, he was far from the Colin Kaepernick or Muhammad Ali of his day. When he stood up to white America – something that took huge personal courage – it was to help himself rather than African Americans as a whole. He expressed no solidarity with other black Americans and even took pains to distance himself from their spokesmen. As Paul Beston writes in his superb history of the American heavyweight division, The Boxing Kings, “[WEB] DuBois and [Booker T] Washington agreed that a black man in the public eye had broader responsibilities to the race. Johnson didn’t think so. ‘I have found no better way of avoiding racial prejudice,’ he wrote, ‘than to act in my relations with people of other races as if prejudice did not exist.’ Individualism was his creed.” Simply put, Johnson lived a philosophy as free from identity politics as a Fox News commentator.

His victories brought pride to millions of African Americans but the victories over white fighters also sparked race riots in which perhaps hundreds of men and women were injured and more than a few died (at least 20 reported killed after his 1910 fight with the beloved former champ Jim Jefferies). But Johnson took no pains to calm the troubled waters he had stirred.

In the 2004 biography, Unforgivable Blackness (a companion piece to the Ken Burns documentary), Geoffrey Ward attacked the narrative of Johnson as a role model for black activists. “He never seems to have been interested in collective action of any kind. How could he be when he saw himself always as a unique individual apart from everyone else?’’

Despite his suffering at the hands of a prejudiced boxing establishment, Johnson did little to help other black fighters. He ignored challenges from the other great black heavyweights of his era, particularly the man who many regarded as the uncrowned champion, Sam Langford (the pair had fought before Johnson won the heavyweight title, with the much larger Johnson said to have won easily). Instead, he fought well-known white boxers. Johnson was a far superior fighter than the vast majority of white boxers he routinely beat, even when umpires and crowds were against him. That infuriated white America, which was determined to take him down. In 1913, the bigots succeeded. After relentless investigations into his relationships with white women, Johnson was convicted (by an all-white jury) of violating the Mann Act, transporting a prostitute across state lines in a decidedly shaky case.

As Jesse Washington wrote on The Undefeated: “The first black heavyweight champion was wrongfully imprisoned a century ago by racist authorities who were outraged by his destruction of white boxers and his relationships with white women.” Johnson promptly fled to Europe where, he said, he would be treated “like a human being”. He returned to the US in 1920 and served 10 months of his one-year sentence.

In 1927 Johnson published a memoir, In The Ring and Out, which was surprisingly well received. With the book, Johnson, in effect, printed his own legend. In 1946 he was driving to New York to watch a Joe Louis fight – Johnson, jealous of the second black man to win the heavyweight title, derided Louis’s abilities and enjoyed baiting him from ringside. Johnson crashed his Ford into a light pole near Raleigh, North Carolina – after apparently leaving a diner that refused to serve him because of his race – and was pronounced dead at 68.

That was the end of an amazing life, but not of the Johnson legend. Twenty years after his death, in an era of burgeoning black consciousness, Johnson was elevated as the kind of hero he never aspired to in life. In 1967, Howard Sackler’s play, The Great White Hope, made its debut. It starred a perfectly cast James Earl Jones as Jack Jefferson, a barely disguised sketch of Johnson, and in 1970 the play was adapted into a much admired film. A year later, the coolest man on the planet, Miles Davis, released Jack Johnson (later reissued as A Tribute to Jack Johnson) as the soundtrack for a documentary.

Unless, that is, the coolest man on the planet was Muhammad Ali. Ali sometimes sounded as if he thought he was the reincarnation of the first black champ: “I am Jack Johnson!” he was fond of saying. But Ali was far more than that. He was persecuted for his association with the Nation of Islam – then known as the Black Muslims – and for his political views, especially his refusal to be inducted into the armed forces during the Vietnam War on moral grounds. Johnson wouldn’t have come within a mile of the Black Muslims. And if the US government had tried to draft him during a war, he’d have left the country rather than face the consequences.

Over the years many politicians have floated the idea of posthumously pardoning Johnson, most recently Senator John McCain. Johnson did get a bum rap on the Mann Act, but the Jack Johnson whose brand Republicans want to “save” is the Johnson character of The Great White Hope, the man anointed by Davis and Ali.

And why a pardon for Johnson now? Perhaps wisely, Barack Obama took a second pass in 2015 (the first was in 2009) when Congress approved a bill which included a resolution to pardon Johnson. As Jesse Washington noted, “Exonerating Johnson would have opened Obama up to racial repercussions unique to the first black president … Obama was focused on clemency for living victims of mass incarceration policies, which disproportionately affect the black community.” If Obama had pardoned Johnson, you can bet Fox News would have revived the real Johnson and screamed bloody murder.

So why has Trump decided to be Johnson’s savior? There is perhaps a feeling that Trump would use a pardon to score points over Obama. Washington feels that “a pardon would provide Trump with an opportunity to do something, albeit symbolic, about racial injustice. Trump’s Justice Department is reviving the ‘tough on crime’ policies that created the racially biased disaster of mass incarceration – the exact catastrophe that Obama tried to mitigate with both policy and his huge number of commuted sentences.”

So should Johnson be pardoned? After all, the Mann Act rap on Johnson never had much credence. Gerald Early, chairman of Black American Studies at Washington University in St Louis and editor of, among other books, The Muhammad Ali Reader, says: “I think it is fine to pardon Johnson. It was obviously a racially motivated prosecution that was done under a very poorly conceived piece of legislation. But there were other questionable or debatable prosecutions under the act that should be looked into as well, Chuck Berry’s for instance. In as much the law is an example of federal overreach and has clearly not done well what it was purported to be trying to do – namely, protect women from being prostituted – probably many who were imprisoned under the act should be pardoned.”

When Louis lost his first fight with Schmeling in 1936 in New York, African American men openly wept on the streets of Harlem; some suffered heart attacks listening to the fight on the radio. The African American singer Lena Horne, performing at a club that night, broke down when she heard the news. Her mother reproached her, “You don’t even know the man.” Horne replied that she didn’t have to know him: “He belongs to all of us.”

And so Louis does, then and now. Much more so than Johnson, who never really belonged to anyone but himself. Maybe, in Johnson, Donald Trump sees a kindred spirit.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion