Editor's Note: On February 13, 2019, after a final attempt to reestablish contact, NASA officials announced the formal end of the Opportunity rover’s 15-year mission to Mars.

Mired in dust on the afternoon of June 10, 2018, NASA’s Opportunity rover received a final command from Earth. Take a photo of the sun, the Deep Space Network sang in code. Send telemetry.

The rover’s cameras could barely see through all the swirling dust, which had been blown aloft by a planet-spanning storm. The sky was darkening, and Opportunity’s batteries, powered by sunlight, were draining. The reply was grim. The last transmitted image showed solar radiation was one fortieth its pre-storm level. Power was low: just 22 watt-hours, down from a normal 300 watt-hours on the solar panels. That’s enough to run a typical food processor for about five minutes.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Minders on Earth prepared to let Opportunity hunker down for the dust storm, the worst such event ever witnessed in the more than four decades robots have been occupying Mars. On June 10 the rover woke up briefly, but its energy was too low to send a message home, and it fell silent. In the following weeks Opportunity would grow cold. Everyone hoped that once the winds died down and the Martian skies cleared, the solar panels could charge enough to rouse the rover and prompt it to call home.

.jpg?w=900)

This series of images shows simulated views of the darkening sky above Opportunity during a global dust storm in summer 2018. At left, the sun is so bright its glare fills the frame; at right, the light is so obscured by dust the sun can scarcely be seen. Credit: NASA, JPL-Caltech and TAMU

So Opportunity waited, and everyone who cares about it also waited while Mars calmed down. Finally in September came good news from the other side of the planet; orbiters and the Curiosity rover saw the atmosphere clearing. Yet Opportunity lay silent.

People at NASA began trying to wake it up. By January 22, they had sent 600 recovery commands. These lines of code cannot, by design, be plaintive. But humans can, and many of them started sending messages of their own. The messages were as much to one another as to the rover, and they were largely the same: Wake up, Oppy. Come back.

Oppy did not. Last weekNASA officials announced a new set of commands were being beamed to the still-silent rover instructing it—pleading with it, really—to reset its clock and cycle through its radio antennas. But even optimists admit this last-ditch effort has a low probability of success.

Very soon, it seems, the agency will be forced to declare the rover’s mission complete—and the storied Mars Exploration Rover program officially over. Opportunity has endured for 15 years on the Red Planet, 61 times longer than its 90-day warranty. In NASA’s family of interplanetary explorers Opportunity will be survived by its rover descendant, Curiosity, as well as its cousin the InSight lander. It has been preceded in death by its closest kin—its twin, Spirit.

As they grappled with the growing certainty the rover had met its end, several of the mission’s scientists and engineers were philosophical, even celebratory in their measured optimism. But their sadness is palpable. “You can always look back and say, ‘This is a rover that way outlived her expectations and accomplished a lot.’ But that doesn’t make the grief go away,” says Mark Lemmon, an atmospheric scientist at the Space Science Institute. “It’s odd to think about grief being associated with a machine. But it’s a part of our lives. We worry about it; we think about its power, its usage of energy, like a care-and-feeding kind of thing. It’s not just a piece of machinery. It obviously is that, but also something that’s connected to everybody. We’ve gone through 15 years of living our lives, with operating the rover on Mars being the one constant thing in that,” he notes.

COMING OF AGE

Spirit and Opportunity, also known by their formal title as Mars Exploration Rovers A and B, are well equipped robot geologists. They each are outfitted with a five-foot-tall, camera-topped neck called a mast, along with rock-grinding tools, scoops and multiple spectrometers to suss out minerals and rock compositions. They were designed to last three months—and NASA sent two partly because the agency wanted to hedge its bets in case one didn’t make it. “No one, on the engineering team or the science team, had the foggiest idea that Opportunity would still be operating after 15 years. It’s just a well-made American vehicle,” says Ray Arvidson, the mission’s deputy principal investigator and a planetary scientist at Washington University in Saint Louis. Together, they totally changed everything we know about the planet most like Earth.

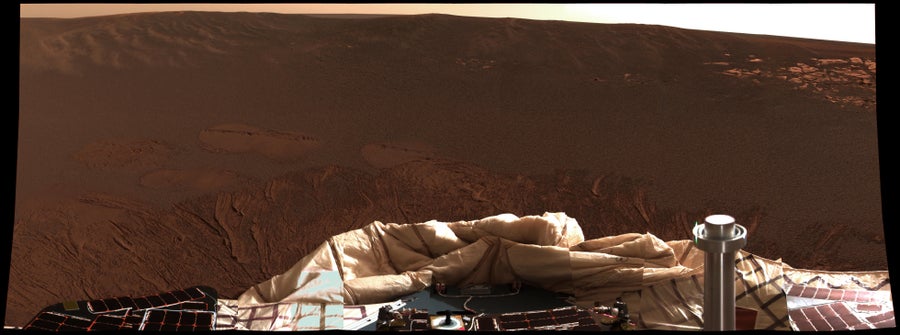

Opportunity landed on Mars January 25, 2004, in a small depression called Eagle Crater, just 20 days after Spirit landed on the other side of the planet. Abigail Fraeman was 15, obsessed with astronomy and Star Trek, and was at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory that night after winning a contest sponsored by the Planetary Society.

The first panoramic color image beamed back by Opportunity, shortly after its landing in Eagle Crater. Credit: NASA, JPL and Cornell University

“It was awesome. When it sent back pictures from Eagle Crater, it was totally different from any pictures of Mars we had seen. There were these smooth, dark sands that were just totally alien,” she says. “The scientists started saying, ‘Oh my gosh, there’s bedrock, I see cross-bedding,’ and they were so excited. I was like, ‘wait a minute, you can do this as a job? You can see that, and look at those pictures and understand the significance of what it means?’”

Today Fraeman is the rover’s deputy project scientist, and until June she spent her days working with engineers and scientists to design the rover’s activities. After her night at JPL she went on to study planetary geology in college and attended graduate school at Washington University, where she studied with Arvidson. Many Mars geologists earned their doctorates under his tutelage; his office in the Earth and Planetary Sciences Department serves as an Opportunity hub as well as the home of the Planetary Data System, which archives and distributes every piece of information U.S. robots have gathered from other rocky worlds. Washington University is Opportunity’s spiritual home, in a sense, along with mission control at JPL and the rover research office at Cornell University.

When Fraeman took the job at JPL, the former lab director, Charles Elachi, encouraged her to draw a chart comparing her life with Opportunity’s. She marked milestones like “high school graduation” or “earn PhD” along rover milestones like “rover finds gypsum” and “rover reaches marathon distance.” She still has the chart. “You just see this rover there all along, and it really gives a sense of just how long this thing has been going,” she says. “The rover set the course of my life, literally.”

DUST DEVILS, BLUEBERRIES AND WORLD-FAMOUS ROCKS

Opportunity and Spirit were tasked with finding evidence of ancient water on Mars—and they did, in torrents. They found weird rock formations shaped by flowing water. They found clay formations that could have been hospitable for microbes long ago. Opportunity studied more than 100 individual craters, and drove more than a marathon’s distance across the surface of the fourth planet. Together, the twin rovers brought Mars to life in a way no other explorers had before.

A year into the mission, the rovers’ solar panels had slowly accumulated dust—Martian regolith is powdery, fine stuff like flour—and their sun-collecting capacity had slowly diminished. One day, Spirit’s were suddenly clean. Engineers were perplexed, and scrutinized selfies from the rover to figure out what happened, Lemmon recalls.

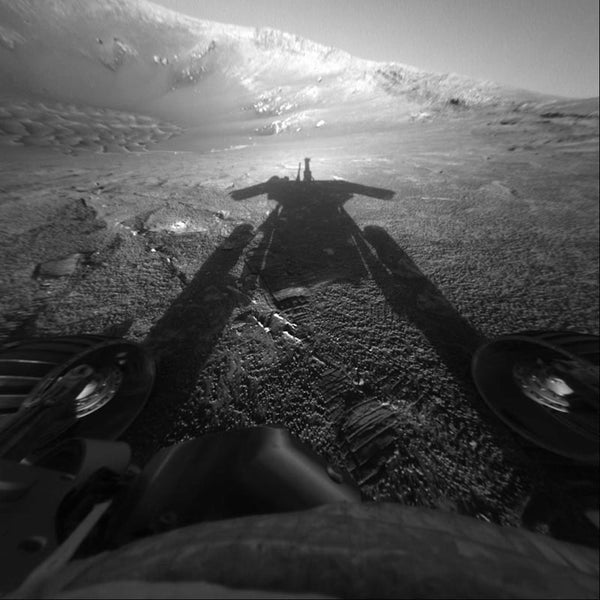

Looking downslope from its perch high on a ridge, Opportunity caught this view of a Martian dust devil twisting through the valley below in March 2016. Similar dust devils had given Opportunity’s sister rover, Spirit, a new lease on life when they cleared its solar panels of accumulated debris. Credit: NASA and JPL-Caltech

“It happened overnight. You could see the trails behind the mast, a wind tail behind it where the dust had blown. Then we started seeing dust devils in the images,” he says. “We put together a series of still pictures with the navigation cameras, and produced dozens and dozens of these dust devil movies. Those were so cool, because they made Mars dynamic. All of a sudden, we can look at Mars and see things happening. It wasn’t just a planet with rocks on it.”

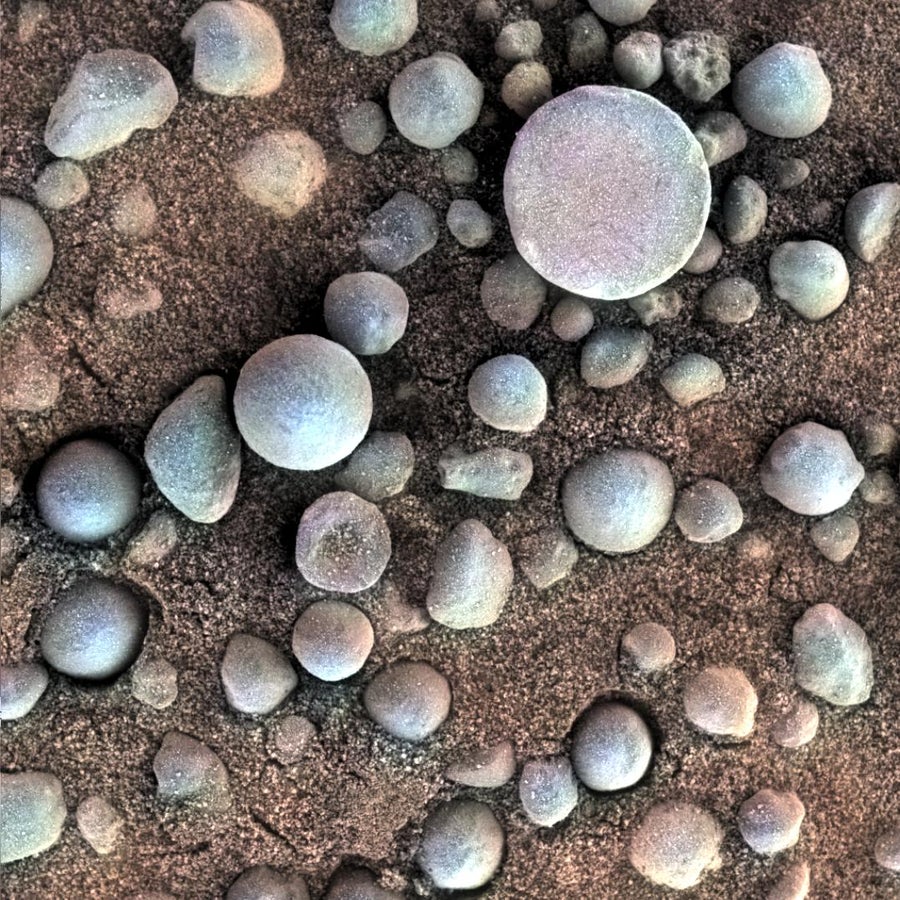

Through Opportunity, even the rocks took on lives of their own. Opportunity found odd wind-carved “aeolian” rocks, iron-rich spheres nicknamed “blueberries,” even meteorites. Lead rover driver Heather Justice, whose 16th birthday was the day Opportunity landed, found one of the most famous rocks of all.

After training for many months, Justice was cleared for her first solo drive January 4, 2014. Her job was to tell Opportunity to turn around, move a little to one side and situate its arm over some bedrock the team wanted to drill. A couple days later Opportunity sent some images so the engineers could verify it was on the right spot. “We’re looking at the picture, there’s the bedrock, and then one of the scientists says, ‘Hey, there’s something that wasn’t there before.’ They were like, ‘Hey, did something break off the rover?’” Justice recalls. “I’m starting to panic. Don’t tell me I broke something on my first drive!”

A plump, rounded white object had appeared in the image. It resembled a jelly doughnut. The team frantically directed Opportunity to take selfies so they could determine whether any hardware was missing, but all was fine. The internet was not fine, however. Headlines around the world speculated the object was a message, an alien life-form, a message from an alien life-form, and other unlikely scenarios. Actor William Shatner of Star Trek fame joked on Twitter NASA should address “Martian rock throwers.” A private citizen filed a lawsuit alleging the rock was a fungal spore, and tried to compel the space agency to investigate.

A view of Martian “blueberries” recorded in April 2004 using the microscopic imager on Opportunity’s robotic arm. Thought to have formed in liquid water, these small, spherical mineral deposits are further evidence for Mars’ warmer, wetter past. Credit: NASA, JPL-Caltech, Cornell University and the U.S. Geological Survey

Ultimately, the team determined Opportunity had driven over a rock, flipping it and scraping some dirt from its surface to expose white beneath. “It’s a really interesting balancing act for all of us to figure out how we can get the most interesting science, without doing too much or endangering the rover,” Justice says. “There is no one there to watch it and stop it if something goes wrong.”

Justice notes most team members are fond of the rover, but they are fonder of one another, and the human bonds their thinking metal box represents. “It’s really exciting for us to come together, with all our expertise, and go explore another planet. The thought of losing that…” she trailed off. “It’s not just losing hardware, but the thought of losing our connection to Mars.”

THE LONG GOOD-BYE

On September 14, 2018, or Opportunity sol 5,204—that’s 5,204 Martian days, which are slightly longer than Earth days—I sat with Arvidson in his office as he worked on a scientific paper rounding up some of the rover’s findings at its final resting place, near the rim of Endeavour Crater. Arvidson and other scientists were debating the nature of a deltalike feature they nicknamed Perseverance Valley, “because we never thought we’d get there.” It might be wind-carved or it might be the work of water. The robot geologist had been trying to find out.

Arvidson says he is focused on the rover’s legacy, and described his feelings as philosophical. He is soft-spoken and deliberate, a consummate scientist. But even he talked about Opportunity in anthropomorphic terms, explaining how without enough power, “she goes back to sleep,” and comparing its exploits with the travels of a favorite adventurous cousin. Weekly phone meetings between the scientists and engineering team at JPL kept everyone updated, but were also an excuse to stay connected to one another, like extended family hovering over a sick loved one.

Arvidson had been here before. He has worked on every Mars mission since Viking 1, the first lander to send a photo from the surface of another planet, and watched many a robot come and go, most recently Spirit, Opportunity’s twin.

Spirit lasted until March 2010, when it got stuck in a soft sand bed due in part to two broken wheels. It could not turn its solar panels toward the sun, which was slowly sinking on the winter horizon, and NASA declared the mission over in May 2011. During that 14-month wait, Mike Siebert, a former mission manager, would occasionally drive to JPL in the middle of the night, sometimes between 2 A.M. and 6 A.M., hoping to hear a signal. “My thought was, every time you did it, this could be the shift. You get one tone back from that spacecraft, and suddenly you are in full high gear,” he recalls.

He continued working on Opportunity until June 2017, when he left JPL for a new job in Boulder, Colo. Seibert and his wife were married five days after his final shift. They wanted to hold the wedding on a summer Saturday, so they picked June 10: Spirit’s launch date. “It will hurt to lose Opportunity, no matter what. But it’s the most successful surface mission ever—period,” he says. “When contact was lost, it was killing me to not be there trying to figure out, how do we restore contact? The most I can do, if I happen to be in Pasadena, is to buy some beer for my friends.”

In September 2018, after the skies over Opportunity had cleared, NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter snapped this image of the rover sitting silently on the surface far below. The rover is visible as a small, light-colored object at the center of the white box. Credit: NASA

Steve Squyres of Cornell University, the principal investigator and godfather of the mission, says Spirit’s demise was noble, and believes the same is true for Opportunity. “I have always felt there were only two honorable ways for this mission to end. Either we wear the thing out or Mars just reaches out and kills it—and there’s nothing we can do,” he says. He could not say how he would feel at Opportunity’s wake but predicted the mood would be both celebratory and somber. “We’ll see. I mean, I’ve got 30 years of my life invested in this,” he says. “At every step, the emotions have surprised me.This sounds really weird but at the launch it was kind of hard to say good-bye. You pour your heart and soul into these things, and strap it to a rocket and fling it out into space—then it’s as gone as it is ever going to get. So it was hard to let go. I wasn’t expecting that.”

When I leave for lunch on sol 5,204, Arvidson walks me down the hall and we stop at a scale model of the rover, parked near the entrance of Washington University’s Rudolph Hall. I’ve seen it before, but each time I visit it seems bigger than I remember. Its solar panels, spread lotus-like toward the sun, are as wide as a couch. Its mast reaches eye level. Its arm, with its three flexible joints, is longer than my own.

I stare at the mast’s eyelike cameras, one of the features that gives the rovers an open, petlike countenance. I imagine it parked on another rocky world 200 million kilometers from here. Its solar panels are caked in rust-colored flour. Its joints have grown creaky, its tools degraded, its protruding antenna scoured by flying sand. It is looking down a slope, en route to a channel where water maybe flowed eons ago, in a place people nicknamed Perseverance Valley. The orange sky is tinged with dust, but it is clearing. The view is sublime.