Neanderthals Had Strong Social Support Structures, Cared For Injured And Weak: Study

The common understanding and colloquial usage of the word “Neanderthal” evokes a brute that is far removed from us humans who stand above other animals in part due to our social nature and our intelligence. But Neanderthals, or Homo neanderthalensis, were humans too, and increasing evidence is emerging of their smartness and strong social nature as well.

About 50,000 years ago, during the Pleistocene epoch, at a time when carnivores roamed the land, being physically strong and having all your senses working in perfect condition were almost certainly among the important factors that kept you alive. And yet, the remains of a Neanderthal man from the time who lived into his 40s (considered old by longevity standards at the time) show he not only suffered from a number of injuries but also had his right forearm amputated and was deaf too.

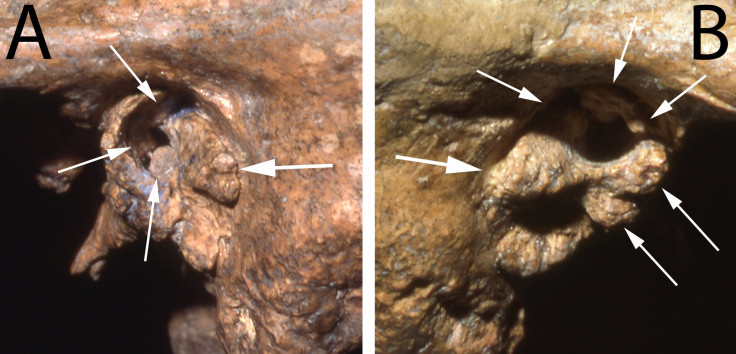

The remains of this Neanderthal are called Shanidar 1 and were excavated in 1957 during excavations at Shanidar Cave in Iraqi Kurdistan. Erik Trinkaus from Washington University in St. Louis and Sébastien Villotte of the French National Centre for Scientific Research analyzed the remains once again and confirmed “that bony growths in Shanidar 1’s ear canals would have produced a profound hearing loss,” according to a WUSTL statement Monday.

It would seem that the right side of Shanidar 1’s body fared much worse than the left, deafness notwithstanding. “He sustained a serious blow to the side of the face, fractures, and the eventual amputation of the right arm at the elbow and injuries to the right leg as well as a systematic degenerative condition,” the statement said.

But the deafness takes on a significant role when looking at personal safety in an environment full of predators and that brings into play the social support factor.

“More than his loss of a forearm, bad limp and other injuries, his deafness would have made him easy prey for the ubiquitous carnivores in his environment and dependent on other members of his social group for survival. … The debilities of Shanidar 1, and especially his hearing loss, thereby reinforce the basic humanity of these much-maligned archaic humans, the Neanderthals” Trinkaus, who co-authored a paper on the subject with Villotte, said in the statement.

Some other Neanderthal remains that have been found previously also show injuries and limited use of limbs that would have made the individuals who once inhabited those remains dependent on their social support systems to survive. The case of Shanidar 1 is unusual because it also involves the impairment of one of the five basic senses.

In their paper, the researchers conclude: “Survival of these sensorily impaired archaic humans despite the rigors and dangers of a Middle-to-Late Pleistocene foraging existence… [indicate]… a substantial degree of social support, especially given Shanidar 1’s plethora of other impairments.”

The open-access paper, titled “External auditory exostoses and hearing loss in the Shanidar 1 Neandertal,” appeared online Friday in the journal PLOS ONE.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.