Teaching the Bible in Public Schools Is a Bad Idea—For Christians

If many evangelicals don’t trust public schools to teach their children about sex or science, why would they want those schools teaching scripture?

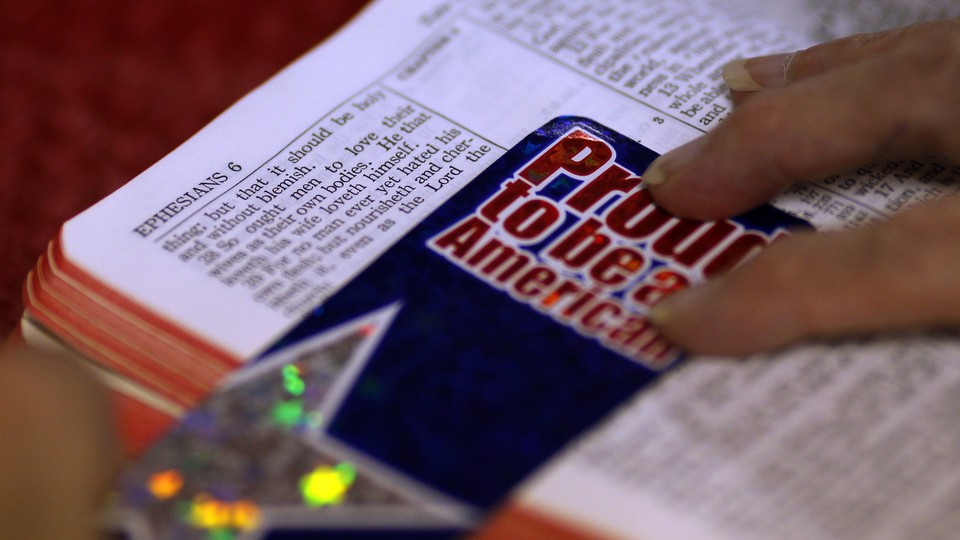

Shortly after Fox & Friends aired a segment about proposed legislation to incorporate Bible classes into public schools on Monday morning, President Donald Trump cheered these efforts on Twitter. “Numerous states introducing Bible Literacy classes, giving students the option of studying the Bible. Starting to make a turn back? Great!” Trump wrote.

The segment followed a USA Today report on January 23 that conservative Christian lawmakers in at least six states have proposed legislation that would “require or encourage public schools to offer elective classes on the Bible’s literary and historical significance.” These kinds of proposals are supported by some prominent evangelicals, including Family Research Council president Tony Perkins, the Texas mega-church pastor John Hagee, and even the actor Chuck Norris. They argue that such laws are justified by the Bible’s undeniable influence on U.S. history and Western civilization.

If conservative Christians don’t trust public schools to teach their children about sex or science, though, why would they want to outsource instruction about sacred scripture to government employees? The type of public-school Bible class that could pass constitutional muster would make heartland evangelicals squirm. Backing “Bible literacy bills” might be an effective way to appeal to some voters, but if they were put into practice, they’re likely to defeat the very objectives they were meant to advance.

Debates over whether religion has a place in public schools are as old as public education itself. Some of America’s earliest grade schools were private and church-run, and they almost always included religious education. In colonial New England, which had early public schools, religious texts, including the Bible, were generally assigned a central role. In the 19th century, however, as a greater array of local governments started public schools to provide nonsectarian education for all children regardless of religion or social status, that began to change.

As the historian Steven K. Green writes in The Bible, the School, and the Constitution: The Clash That Shaped Modern Church-State Doctrine, many of these common schools still included Bible reading and were influenced to some degree by Protestantism. But they largely avoided providing devotional content and eschewed proselytizing students. After all, as Green says, “a chief hallmark of nonsectarian education was its purported appeal to children of all religious faiths.” The ostensibly secular nature and mission of these common schools miffed many Protestants at the time, much as they do today.

These early schools were controlled by the states, but the federal government began to assert a greater role in the 20th century, as the Supreme Court started to constrict the presence of religion in public schools. This included the landmark 1948 case of McCollum v. Board of Education, in which the Court ruled that “a state cannot consistently with the First [Amendment] utilize its public school system to aid any or all religious faiths or sects in the dissemination of their doctrines,” as well as the highly controversial 1962 case of Engel v. Vitale, in which the justices declared that compulsory prayer in public schools was unconstitutional because it violated the First Amendment’s establishment clause. These decisions helped spark the modern culture wars and the rise of the religious right, a movement that sought to fight the “secularization of public schools,” which included the reincorporation of prayer and Bible reading.

Donald Trump is an unlikely choice to play the role of champion for this cause. The thrice-married real-estate mogul who claims to have never asked God for forgiveness has said that he attended Manhattan’s Marble Collegiate Church, but the congregation responded that he is not “an active member.” Trump claimed on the campaign trail that the Bible was his favorite book, but he couldn’t cite his favorite verse when asked. (He finally named his favorite verse eight months later, but seemingly didn’t understand how to interpret or apply it.)

But while Trump might not care much about the Bible personally, he knows it is politically important to many of the conservative Christians who support him. According to a recent study conducted by the Barna Group, a staggering 97 percent of churchgoing Protestants and 88 percent of churchgoing Catholics said they believed that teaching the Bible’s values in public school was important. Trump’s odd tweet is likely an effort to shore up his base, rather than a passionate plea for a new educational initiative.

Following Trump’s tweet on Monday, some legal scholars argued that teaching the Bible in any form in a public school would violate the First Amendment. But others, such as John Inazu, a law and religion professor at Washington University in St. Louis and the author of Confident Pluralism: Surviving and Thriving Through Deep Difference, believe that this would depend on the nature of the classes.

“The Court’s approach to the establishment clause is convoluted and unclear, so it is difficult to say whether a Bible literacy class is unconstitutional,” Inazu told me. “It’s a historical fact that the Bible has influenced Western civilization and U.S. history, so it’s plausible that you could teach a class like this if it is done in a way that promotes cultural literacy.”

Inazu added that the courts would also consider the motive behind instituting such classes. If they determine that the motivation behind Bible-literacy bills is to privilege Christianity, the classes could be ruled unconstitutional. That’s bad news for those pushing these bills because, as USA Today reported, they are the product of “an initiative called Project Blitz coordinated by conservative Christian political groups” who seek to “advocate for preserving the country’s Judeo-Christian heritage.” (It’s telling that they aren’t also advocating teaching the Koran or the Bhagavad Gita as part of world-history education.) So even if these bills pass, the classes they’ll spawn will likely not last long.

But assume for a moment that no ulterior motive is behind these bills, and that the conservative Christian activists and lawmakers are merely deeply concerned that America’s schoolchildren receive a better cultural-historical education. And also assume that teaching a Bible class in a public school is not a violation of the establishment clause, as many legal scholars claim. As Inazu pointed out, for a Bible class in public school to have any hope of passing constitutional muster, it would need to be academic rather than devotional. Which is to say, it couldn’t actually impart biblical values to students, and it would need to draw from scholarly consensus. And this is where the whole enterprise would backfire.

Start at the beginning. Many conservative Christians believe that the opening of the book of Genesis teaches a literal seven-day creation of the world by God around 6,000 years ago. But most academic Bible scholars believe that this text should be read poetically, and not as history or science. They interpret these passages as making theological points from the perspective of its ancient writers, rather than commenting on the truthfulness of Darwinian evolution or any other modern debate. Additionally, most conservative Christians believe that when Genesis tells about Adam and Eve, it is referencing two historical figures who were the first humans who ever lived. But geneticists assert that modern humans descend from a population of people, not a single pair of individuals.

The potential problems don’t stop with the Bible’s creation narrative. Conservative Christian parents across America teach their children a Bible story about a man name Noah who built a giant boat to house all of Earth’s animals during a cosmic flood. But scientists say that such a flood is impossible; there isn’t enough water in the oceans and atmosphere to submerge the entire Earth. Historians point out that strikingly similar stories are told in sources other than the Bible, some which pre-date the biblical tale. This story, many scholars conclude, was not meant to be literal. And what of the Bible’s story of Jonah being swallowed by a great fish and surviving in its belly for three days? A marine biologist will tell you it’s anatomically implausible, and many biblical scholars say the story is intended to be understood allegorically, anyway.

That evangelical understandings of the Bible differ from scholarly consensus doesn’t make them incorrect, but it does mean that the material taught to public-school students would likely diverge from what they are learning in church and at home. Can you imagine young Christian students coming home from school and informing their parents that they’ve just learned that all these cherished Bible stories are in fact not historically correct? How would evangelical parents react when their fifth grader explains that their teacher said the Apostle Paul said misogynist things and advocated for slavery? And what if the teacher decides to assign the Catholic version of the Bible, which has seven books that Protestants reject as apocryphal?

And this only addresses issues of historicity and interpretation. The social teachings of the Bible could also create issues in a public-school setting. A recent thesis project in sociology at Baylor University suggested that increased Bible reading can actually have a liberalizing effect, increasing one’s “interest in social and economic justice, acceptance of the compatibility of religion and science, and support for the humane treatment of criminals.” Every community that reads the Bible places unequal stress on certain books or passages. While evangelicals are generally more politically conservative, teachers in public schools might choose to emphasize the Bible’s many teachings on caring for the poor, welcoming the immigrant, and the problems of material wealth.

Bible-literacy bills are unlikely to pass in most states, and even if they do, they might be soon ruled unconstitutional. But conservative Christian advocates would do well to think through the shape these classes will likely take if their efforts are successful. They might end up getting what they want, only to realize that they don’t want what they’ve got.