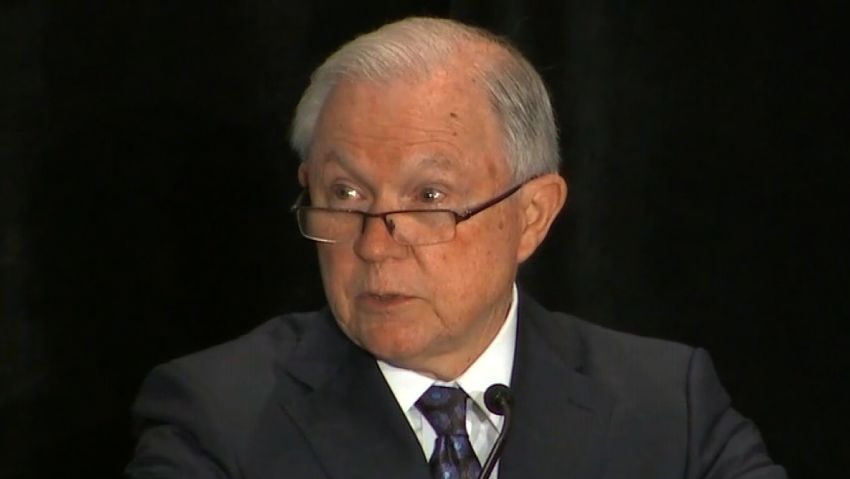

When Attorney General Jeff Sessions ruled that domestic violence and gang victims are not likely to qualify for asylum in the US, he undercut potentially tens of thousands of claims each year for people seeking protection.

But in a footnote of his ruling, Sessions also telegraphed a desire for more sweeping, immediate reinterpretations of US asylum law that could result in turning people away at the border before they ever see a judge.

Sessions wrote that since “generally” asylum claims on the basis of domestic or gang violence “will not qualify for asylum,” few claims will meet the “credible fear” standard in an initial screening as to whether an immigrant can pursue their claim before a judge. That means asylum seekers may end up being turned back at the border, a major change from current practice.

“When you put it all together, this is his grand scheme to just close any possibility for people seeking protection – legally – to claim that protection that they can under the law,” said Ur Jaddou, a former chief counsel at US Citizenship and Immigration Services now at immigration advocacy group America’s Voice. “He’s looking at every possible way to end it. And he’s done it one after the other.”

The Trump administration has focused on asylum claims – a legal way to stay in the US under domestic and international law – characterizing them as a “loophole” in the system. The problem, they say, is many claims are unsuccessful, but in the meantime as immigrants wait out a lengthy court process, they are allowed to live and work in the US and build lives there, leading some to go into hiding.

Experts estimate that most of the migrants from Central America who claim asylum at the southern border are fleeing violence committed by someone other than the government, like gangs or abusive individuals – exactly the type of claim that will be rejected after Sessions’ Monday ruling.

For the impact at the credible fear stage to take effect, it will have to be carried out by USCIS, which handles the initial asylum claim processing.

USCIS spokesman Michael Bars said Sessions’ decision “will be implemented as soon as possible.”

“Asylum and credible fear claims have skyrocketed across the board in recent years largely because individuals know they can exploit a broken system to enter the US, avoid removal, and remain in the country. This exacerbates delays and undermines those with legitimate claims,” Bars said.

“USCIS is carefully reviewing proposed changes to asylum and credible fear processing whereby every legal means is being considered to protect the integrity of our immigration system from fraudulent claims,” he added.

The Trump administration has pointed to the numbers of ultimately unsuccessful claims as evidence of bad faith in the asylum system, and Sessions repeatedly has discussed clearing the way for “legitimate” claims to succeed, though he has not explained how a claim could be known as illegitimate before it is heard.

The credible fear threshold is set to consider that many of the immigrants may speak little English, have little to no legal understanding or education, may fear governmental authorities based on their home countries and may be traumatized from their journey. Roughly 80% of asylum seekers pass that screening, though a smaller share of them eventually achieve asylum.

With tens of thousands of immigrants apprehended crossing the border illegally or showing up at a port of entry without authorization each month, officers applying a new test could immediately start turning back thousands of immigrants, who would likely not know they could pursue their cases before a judge if they asked to, and likely would not have access to legal representation to defend them.

Such an impact would be challenging for immigrant advocates to address quickly. Litigation would almost certainly follow, but it would be difficult to assess at first how many thousands of migrants would be rejected and sent back to the violence they were fleeing.

“The present leadership of USCIS would probably be politically inclined to do that,” said Stephen Legomsky, a law professor at Washington University School of Law and a former chief counsel of USCIS and senior counselor at DHS. “(It) will probably kill off a very large number of asylum claims, and that means a very large number of people will be sent back to conditions where their lives threatened by violence.”

Broader changes

In other footnotes, Sessions also hints at broader changes to asylum he sees within the law.

In one, Sessions suggests that families may not qualify as groups under asylum law – though he notes he can’t rule on that on this particular case.

The last footnote would have implications for every kind of asylum claim. Sessions argues that asylum is itself “discretionary” – meaning that even if an applicant meets the eligibility requirements, they should have to prove on top of that why they deserve asylum.

Sessions suggests that if an asylum seeker passed through another country and didn’t seek asylum there, or came into the US illegally, those could be factors that a judge could use to reject asylum.

Legomsky argued that placing such a burden on an asylum seeker – especially as many of them don’t have access to a lawyer and are not given one by the government – could be prohibitive for many.

Those changes would likely work their way through the courts for years before they could finally be implemented.