Why American Moms Can’t Get Enough Expert Parenting Advice

Women are struggling to balance work and family, and they're hoping that the latest podcast, book, magazine article, or class is going to offer them an answer.

Studying up. Researching. Seeking advice from others. This is Kristine’s approach to any new challenge. “If I’m doing something,” she told me, “I read a book about it. If I was going to tile my kitchen, I’d get a book about how to tile a kitchen. It’s my personality.”

This was especially true for parenting. Before becoming a mother, Kristine—a white, married professional—pored over parenting books late into the night. “I started off reading What to Expect When You’re Expecting,” she said when we met in her sparse office in downtown Washington, D.C. “I was educating myself. I felt this obligation to deliver a child safely, to do healthy things.”

Kristine is one of 135 working, middle-class moms I interviewed in the United States, Italy, Germany, and Sweden from 2011 to 2015 for my book, Making Motherhood Work: How Women Manage Careers and Caregiving. (Like other mothers I talked with, Kristine was granted anonymity as a condition of participation in my research, as is common practice in sociology.) When I asked what they thought being a good mother means, many of the American women replied with some version of “I read this really interesting article about this,” volunteering its explanation as a proxy for theirs. They routinely recited the views of experts they had gleaned from books, articles, podcasts, classes, listservs, blogs, and message boards—but a personal definition rarely followed.

But the European women I spoke with rarely invoked expert views, instead talking about traits they wanted to instill in their children (stability, independence, kindness) and wanting them to feel safe and loved. Take Sara, a mom in Sweden: When I asked her what being a good mother meant, she told me, “Having time with them. I think that’s the most important part. Yeah, just being with them.”

In the United States, women are often expected to put child-rearing ahead of their own needs as an all-consuming labor of love. Yet squaring these high standards with modern economic realities is tough. Today 71 percent of mothers work, and most do so full-time. Though women in the United States are constantly told that they can have a successful career and a rewarding family life, with next to no work-family policies to support them, “having it all” is mostly a pipe dream. In essence, mothers are encouraged to reach for the stars while wearing straitjackets.

How can women provide the type of intensive mothering they believe is expected of them while also working for pay? Most of the time, they can’t. That’s what makes expert advice so appealing to overworked, primarily middle- and upper-class moms. Professionals insist that they possess the elixirs to make the balancing act work. Poor women may find professional advice irrelevant, out of reach, or out of touch. The unsavory truth is that you need time and money to access and implement the advice of parenting experts—resources in short supply for mothers in poverty.

I asked Makayla, a black public-relations executive based in Washington, D.C, what being a good mother meant to her. “My husband and I just went through a parenting boot camp for three Saturdays,” she said. “It’s all about encouraging your kids.” The stubbornness of their 3-year-old son had left them feeling impatient and exhausted. The class reminded them that their son was “no different from any other kid”—they simply needed to refine their approach. The professionals reassured her: His behavior was just “what kids do.”

When I asked Gloria, a Latina sales director with two young children, the same question, she also talked about expert advice. “I have all these parenting books,” she said. “I give my kids choices like, ‘You can have either an orange or an apple.’ I’m okay with either one. They learn how to decide.”

Moms told me they wanted to be more organized, calmer, better at multitasking and temper-tantrum wrangling. So they read books, listened to podcasts, signed up for classes, and joined support groups. One lawyer and single mother with twins said her parenting listserv is full of discussions about specialists to hire for potty-training or lactation help. A white engineer with two young children said she and her husband follow a “respectful parenting” philosophy that she learned about on Facebook. “I read tons of things,” she said. “I have this parenting idea and I know how I want to implement it.”

Expert advice and the consumerism it begets, such as Makayla’s boot-camp experience, are supposed to be palliatives for moms in the face of unreasonable parenting standards. But following expert input—reading yet another article, sitting through yet another parenting class—ends up being a source of stress itself. Complying with middle-class mothering standards becomes an unceasing affair, requiring endless tasks to research and carry out.

Women in the United States confided to me their fears that they hadn’t yet adopted the right parenting approach, weren’t spending enough or the right kind of time with their children, or weren’t knowledgeable enough about their kids’ needs. Of course, it’s not a snap to be a working mom elsewhere, and the United States isn’t the only country where mothers are subjected to sky-high parenting expectations. But middle-class moms in the U.S. seem to turn to expert advice more than their European counterparts because they’re largely going about it without much support. Given that child-rearing still falls mostly to mothers, the worries that accompany parenting do as well. And without an adequate safety net for American families, moms have a lot of worries.

According to a 2014 report by Bright Horizons, a child-care provider, 48 percent of working parents in the U.S. worry that family obligations could get them dismissed from their job. These fears are well founded: Women (and sometimes men) are routinely fired because of family responsibilities that keep them out of the office. Without more robust legal protections, paid-parental-leave policies, guaranteed vacation, paid sick leave, or affordable day care, moms in the United States are drowning in stress. One study of 22 industrialized countries found that the U.S. has the largest subjective well-being penalty for parenthood, with the largest “happiness gap” between parents and nonparents. In other words, the low-support environment in the United States means that parenting is particularly taxing and stressful compared with parenting in countries that have more substantial work-family policies.

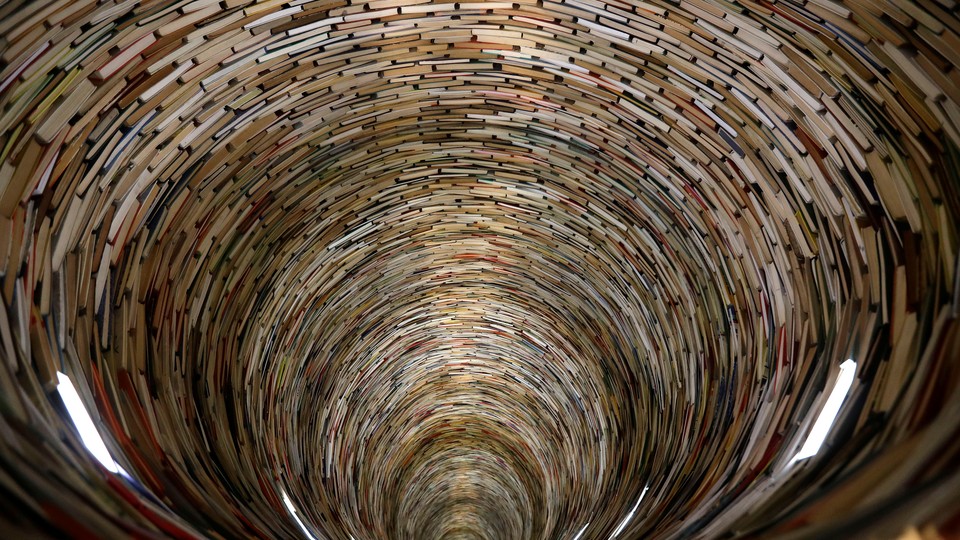

Small wonder, then, that so many American mothers look to professionals for a lifeboat: Read one more article, download one more app, buy one more book, take one more class, listen to one more news story, and you might just find the key to escaping the cascade of stress. Yet this crisis is going to require a societal response, not an individual one. No parenting book, class, or podcast can resolve this hardship—and neither can any individual woman who seeks one out. By its very nature, expert advice implies that the source of mothers’ anxiety is themselves, not the structure of the workplace, or a lack of government policies, or oppressive cultural norms, or gender inequality.

Mothers in many other countries that offer more robust and egalitarian work-family policies can rely on broader support networks to manage child-rearing, which diminishes the need to keep consulting parenting experts. And throughout much of Europe, for example, discriminating against employees for addressing their family responsibilities is illegal. Indeed, parents in certain countries even have the legal right to reduce their working hours once they return to work after having a baby. (Of course not all parents want to reduce their hours, but for many Americans who do, doing so can be quite challenging.)

Until a more equitable model emerges—that is, until the tensions between paid work and caregiving get resolved—millions of American mothers will continue to rely on expert advice. But that’s a solution akin to opening an umbrella to fend off a hurricane; you’re still going to get wet.