Undergraduate and graduate students alike come to the university not only to learn but also to grow as individuals. Many discover or nurture interests and aptitudes through campus activities. A great many also volunteer on behalf of the underserved in St. Louis and distant communities — often building on an ethic of altruism that guided them back in high school. And when some of these students think of an ingenious way to address a need they care deeply about, they typically apply for a Washington University Social Change Grant.

The Richard A. Gephardt Institute for Public Service awards the competitive Social Change Grants (see sidebar) to students university-wide — to ones who complete a rigorous application process and submit worthy, innovative, yet realistic project proposals. Their comprehensive plans, moreover, spell out culturally sensitive ways to make a difference in the lives of people who, often for generations, have been underserved.

“Our students see things that need to be done,” explains Stephanie Kurtzman, director of the Community Service Office and associate director of the Gephardt Institute. “Having entrepreneurial spirits, they are both courageous and bold, and they take action. Think about what the world would lose if they didn’t pursue their dreams.”

Gardening for social justice and the environment

David Fox, Arts & Sciences Class of ’11

Major: philosophy

2009 Stern Social Change Grant

In his third summer as a camp counselor during high school, David Fox decided something was missing. “So my friends and I said, ‘We should make the best camp!’” And that is what Fox is resolved to do.

After high school, Fox spent a year in Israel volunteering near Yerucham, a desert town to which he would return three years later through his Social Change Grant, “Environmentalism as a Conduit to Peace.” Fox’s goal was to develop an organic gardening program for an existing Israeli camp and to teach those children together with Bedouin youth about cooperation, collective achievement, sharing and discovering common ground. He recruited four peers to help teach 35 local children, and together they painstakingly prepared for, built and cultivated five vegetable gardens for a school called Kama. Each garden had a recognizable shape, such as waves, and an environmental message.

Two organizations subsequently sent 160 American teenagers to tour the flourishing site. Fox also worked closely with Kama, so teachers could maintain and use the gardens indefinitely to teach about charity and sustainable relationships to the land.

Today, Fox is involved with three North American camps incorporating organic gardening. With regard to future dreams, he is still developing the prototype for Camp Amir (“the top of the tree”), which he began through his grant. He also is seeking graduate degree programs to prepare him for developing camps in several countries.

Preparing St. Louis’ Chinese immigrants to stop smoking

Dan Feng, Arts & Sciences Class of ’11

Major: anthropology; minors: biology (pre-med) and German

Sophia Li, Arts & Sciences Class of ’11

Majors: anthropology and biology (pre-med)

2010 Kaldi’s Social Change Grant

Dan Feng and Sophia Li surveyed nearly 200 Chinese immigrants at Baili’s Asian Supermarket on Olive Boulevard in St. Louis as part of an internship requirement of the Medicine and Society Program. They found a shocking and dismaying truth: that 45 percent of men, compared to 5.6 percent of women, had experience smoking, meaning they smoke or used to smoke. (Twenty-two percent of men, compared to 1 percent of women, actually currently smoke.)

Chinese men’s smoking intertwines with cultural assumptions about masculinity, propriety and even patriotism, since tobacco helps stoke China’s robust economy. Still, when the two also found that 71 percent of respondents would use or recommend antismoking resources if offered at the St. Louis Christian Chinese Community Service Center, Feng and Li raced into the breach. Their proposal, “Ending Chinese Addiction to Smoking (ECATS),” maps ways to increase working-class Chinese immigrants’ awareness of smoking’s effects on health, as well as options and resources available for quitting.

In concert, Feng and Li hosted national experts on Chinese tobacco control for a daylong campus discussion that produced evidence-based recommendations. One result: An American Lung Association representative is training Chinese physicians, nurses, social workers and other volunteers in medically appropriate, culturally sensitive cessation strategies.

And to ensure ECATS’ survival, Feng and Li are helping to establish an internship for students interested in community health, with guidance from Bradley Stoner, MD, PhD, associate professor of anthropology, director of the Medicine and Society Program, director of the university’s public health minor, all in Arts & Sciences, as well as associate professor of medicine. At the service center, interns will participate in grant-established cessation workshops, explore ways to expand ECATS’ scope and more.

Soccer and self-reflection empower female students in Uganda

Melissa Cochran, Engineering Class of ’12

Major: mechanical engineering; minor: public health

2010 Stern Social Change Grant

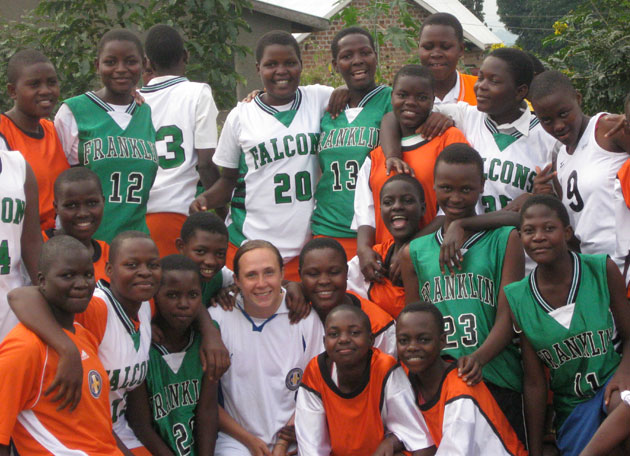

Most of us (excluding the traveler herself) would call Melissa Cochran’s three-day journey to launch her project a feat in itself: flying from hometown New Orleans to Washington, D.C.; New York; Dubai; Ethiopia — and finally, Africa’s Republic of Uganda. The trip was not Cochran’s first: She lived at an orphanage in the town of Nansana in summer 2008 and 2009, while teaching English and math at Nansana Community Primary School — the venue for her Social Change Grant. (Her first two trips followed fundraising she did in New Orleans that produced more than $5,000, sponsors for eight scholarships for the secondary schools — and donations for two cows to provide milk and income for the school.) For Cochran’s project in summer 2010, New Orleans schools contributed “about 500 uniforms and tons of soccer cleats and old shin guards.”

Through her grant project, Cochran addressed the dormant potential of Ugandan female students. She used soccer to empower the elementary school students, most of them orphans about 12 to 20 years old, who had had little previous schooling and no experience playing competitive team sports. Research shows that such activity improves self-esteem, academics and motivation. Engaging in team sports also correlates with lower rates of depression and of high-risk sexual behavior.

Cochran’s breakthrough project sparked a transformation. She introduced fitness and skills training, team bonding and competition — and she developed team leaders to sustain the progress. The girls and young women also developed self-awareness through writing journals, reading books about female athletes, watching inspirational sports movies, and discussing these subjects in groups.

Marshaling youth to halt diabetes’ devastation

Kristen Grant, Medicine Class of ’13

Joseph Song, Medicine Class of ’13

Amanda Stewart, Medicine Class of ’13

2010 Procter & Gamble Social Change Grant

Seventy percent of people in the Republic of Marshall Islands (RMI) develop type 2 diabetes — the world’s highest rate. There, the disease claims limbs and, by middle age, lives. Most Marshallese accept the ravages as inevitable, says Kristen Grant, who spent two years teaching in the RMI and speaks Marshallese. The situation in the tropical Pacific may slowly improve, however, now that she, Joseph Song and Amanda Stewart, all second-year medical students, extended preventive plans from the capital, Majuro, to children throughout the country.

With a shared interest in international and community medicine, Grant, Song and Stewart earned a Social Change Grant. They also earned funding from the School of Medicine’s Forum for International Health and Tropical Medicine — all during the legendary first year of medical school. Grant’s core idea was to educate teachers, who would share the information with their students and incorporate it into take-home assignments. The hope is that knowledge and healthful practices would “trickle up.”

Welcomed by the Ministries of Health and Education, the future physicians spent two months in summer 2010, first convincing educators that prevention is critical to the country’s future. Then, following focus groups and food audits, they developed a “lower level” (for elementary grades four through eight) and “upper level” (for high school) set of resources — a “toolbox.” In this toolbox were curricula, visual aids and “everything the teachers could possibly need to be successful and make the program permanent,” Grant says.

The three worked with elementary teachers from 76 schools during a continuing education workshop, and they worked with high school teachers from six schools as well. At the end of the workshops, Grant, Song and Stewart gave toolboxes to the school principals so that each school would have one available for their teachers to use.

“Working with the teachers was a lot of fun,” Grant says. “They seemed very excited to use the resources, and even started a brainstorming session of how they could extend the material with additional projects in their classrooms!”

Making the program permanent is a high priority for the threesome. “We definitely hope to return in our fourth year!” Stewart adds.

To prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV

Fidel Desir, AB ’10

Major: French

Priya Sury, AB ’10

Majors: anthropology and Spanish

2008 “100 Projects for Peace Grant”*

*Note: These particular grants are no longer available.

In summer 2008, Priya Sury and Fidel Desir, juniors then, arrived at a maternity hospital in the Dominican Republic to initiate HIV-prevention seminars for pregnant women. It was 7 a.m., all waiting rooms were full, and a line was already forming outside the hospital gate as women gathered from around the country for free care.

Fifty first-time mothers at a time met in a seminar room, where the two students talked with them about preventing mother-to-child transmission, demystified condom use, discussed myths about HIV and AIDS, and distributed detailed summary brochures.

The impact was significant. Hundreds of women a day listened intently, asking wide-ranging questions in groups and privately, whereupon Desir and Sury drew on their in-depth research. The mothers agreed to free HIV tests, and those who tested positive enrolled in a vertical-transmission prevention program. Desir and Sury trained hospital staff to continue the work. They also returned to the Dominican Republic in 2010 to visit a different hospital in a different city.

Many of Desir’s and Sury’s ideas grew from their undergraduate work as Annika Rodriguez Scholars. Their grant shaped their future aspirations — and greatly interested their interview committees for medical school.

Sury is now in her first year of medical school at the University of Minnesota, in her home state. Desir, who hails from Puerto Rico, has a one-year deferred enrollment at Johns Hopkins while he works in Thomassique, Haiti, with the Medical Missionaries program as a Global Health Fellow — one of only two such honors awarded annually nationwide.

The Urban Studio Café: “Brewing a great cup of social change”

Claire A. Wolff, AB ’08, MSW ’09

Major: psychology; minor: photography; graduate: social and economic development, with a concentration in management

2008 Kaldi’s Social Change Grant

Old North St. Louis, a mile from downtown, hummed with vibrancy until urban flight and disinvestment after World War II triggered a painful decline. Now the area boasts community gardens and a nearly complete $35 million revitalization project. It has Crown Candy Kitchen. And it has the nonprofit Urban Studio Café, which opened for business nearby at 2815 N. 14th St. in September 2009.

When founder Claire Wolff discovered Old North, she realized people needed jobs and a place to come together. As she was completing a social entrepreneurship course at the Brown School, she received a $5,000 Social Change Grant to launch an urban café. A year later, she expanded her ideas into a 91-page business sustainability plan and won the citywide Social Entrepreneurship and Innovation Competition, which is sponsored by the university’s Skandalaris Center for Entrepreneurial Studies. With a prize of $35,000, Wolff had her seed money to continue building her effort.

Urban Studio Café (www.urbanstudiocafe.org) offers reasonably priced and imaginatively presented food — as well as a “great cup of Joe.” According to Wolff, all profits from coffee and food sales fund art programs and community programs for youth.

Wolff says her Kaldi’s Social Change Grant “has become my identity” as well as a model for Old North’s future social enterprises. She and five Old North neighbors, including three teens, work in her Urban Studio Café — which promotes creativity and joy through live music, art and events. The café also fosters possibility for customers through financial workshops and job-skills training.

With customers and friends from nearby firms, Old North and other neighborhoods mingling in a warm and sharing atmosphere, the gentle undertaking is also “changing mindsets in St. Louis.”

Orchestrating diversity

Max Woods, Arts & Sciences Class of ’11

Majors: mathematics and comparative literature; minors: physics and Spanish

2009 Kaldi’s Social Change Grant

For two summers, Max Woods, a violinist himself, has nurtured young musicians chosen from 11 inner-city middle schools and high schools in St. Louis. The African-American, Chinese, Hispanic, Laotian, Vietnamese and Caucasian students met from 9 a.m. until 3 p.m., five days a week, for eight weeks. They always played from the actual symphonic repertoire.

Although Woods selected the students based on auditions he held at schools, some could not read music at first and had meager comprehension of music fundamentals. Despite such obstacles, every one passed a midterm theory exam that Washington University provided to establish competency levels. Implemented at the Lemp Neighborhood Arts Center through Woods’ Social Change Grant, the Orchestrating Diversity program gets ovations from students and teachers.

“We seek to accomplish nothing less than a comprehensive music education program for inner-city residents between the ages of 5 and 18,” Woods says.

The initiative has become a community effort. A gallery loaned a piano; other sources donated or loaned a bass, a cello, a timpani and various instruments for students who could not afford them and whose schools refused to lend them. Einstein Bros® Bagels donated breakfast; Bon Appétit, lunch; and a police officer escorted children to and from practice and private lessons. Small amounts of community funding have greatly helped as well.

When Woods continues to graduate school, musician-colleagues in the program and the artistic director at the Lemp Neighborhood Arts Center will maintain the tempo.

Becoming an agent of change

Laura Vilines, AB ’06

Majors: political science and English; minors: Spanish and modern dance

2008 Stern Social Change Grant

In the economically depressed coal-mining town of Harlan, isolated in mountainous Eastern Kentucky, Laura Vilines introduced free art camps for children aged 6 to 12. During her sophomore year, Vilines, a native of Bowling Green, Ky., placed calls to Appalshop, a well-known arts organization sponsored by the National Endowment for the Arts in Eastern Kentucky. Appalshop referred her to Artists Attic, a small nonprofit in the Harlan area, and Vilines arranged to partner with the organization.

Vilines recruited three staff members from her hometown to help, including her older brother, who has a degree in vocal music. Her grant covered their housing for the summer and paid a small stipend. The first summer, when Vilines was a junior, “was so phenomenal” that Artists Attic raised funds so her program could continue for the next two summers.

“The community was very receptive,” Vilines says. “I remain in contact with one family especially, and I try to keep tabs on what’s happening.” Arts programming continues in the area, and the permanent theater-set pieces Vilines’ team built are a material legacy.

The experience shaped her future. Vilines wrote her senior honors thesis about access to arts programs in rural areas as a result of national funding sources. She then joined Teach For America, and she developed a project in St. Louis that matched her African-American high school students with African immigrants in the elementary schools. She helped the high school students raise money to visit Africa as well.

Today, Vilines is earning a master’s degree in education policy in order to help provide equal and equitable educational opportunities.

The gift of vision

Joshua Yudkin, Arts & Sciences Class of ’11

Majors: Spanish and international area studies, with a focus on Latin America; minor: Jewish, Islamic and Near Eastern studies

2010 Stern Social Change Grant

Many indigent Mexicans in the state of Chihuahua can’t see, and they need glasses. “Because of this, children can’t learn to read and write, and adults can’t work,” reinforcing poverty and related problems, Josh Yudkin explains. Constant sunlight exposure catalyzes pterygiums, fibrovascular growths on the eye, and creates cataracts so dense that surgical removal can take six times longer than in the United States.

Using his Social Change Grant to serve the Guerrero Surgery and Education Center, 125 miles west of Chihuahua City, was Yudkin’s way of “giving back and staying involved” after he and his dad visited the area during high school. For two weeks a year, the clinic provides more than 60 percent of indigent ophthalmological care in the state. Some patients travel 14 hours by bus and wait two days to be seen, so Yudkin decided to ease the load with services he could render under medical direction. He consulted with physicians in the clinic and in his home state of Texas, and he studied public health (taught in Spanish) in the university’s Study Abroad Program in Puebla.

His work began in May 2010. Yudkin and eager local volunteers spent 18-hour days in desert villages — unloading trucks packed with vision-testing machines, eyeglasses in strengths that data showed are commonly needed, plus educational materials. They assisted hundreds of people, identified surgical patients and prepared their files.

Through his grant journal, Yudkin will create a blueprint for a new clinic outreach plan, and he will also submit a paper to the clinic’s foundations. “My pilot program was designed to empower the people,” Yudkin says.

Judy H. Watts is a freelance writer based in St. Louis and a former editor of this magazine.

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.