The Chinese Communist Party helped shape Qiu Xiaolong, PhD ’95, into the successful novelist and poet he is today — though likely not in the way its leaders intended. That process began when they gave him the assignment for his first published writing: his father’s confession.

“My father had to be mass criticized, to stand on stage as a target, where people denounced him and chanted slogans for hours.”

—Qiu Xiaolong, PhD ’95

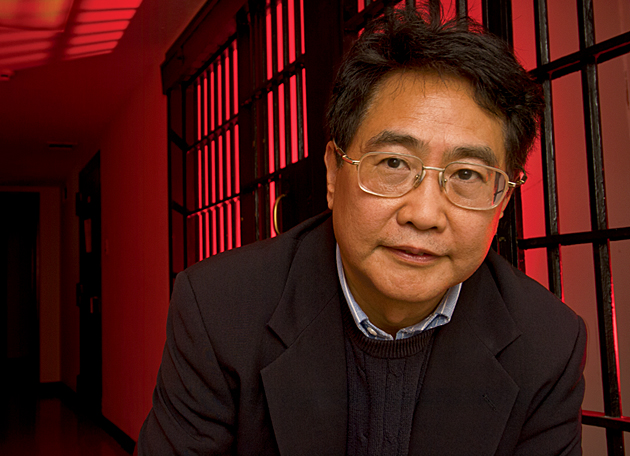

“It happened to lots of families,” says Qiu (pronounced “Cho”), now an advisory member of WUSTL’s Center for the Humanities, who has also taught Chinese literature and comparative literature at the university. “We were a ‘black’ family — politically unreliable, a class enemy.”

In the class system introduced by party leader Mao Zedong, those who had been business owners or rural landlords before 1949 were labeled as “capitalists.” This so-called black class, which also included many writers and other “counter-revolutionaries,” Qiu says, was opposed by the favored “red” class, the Marxist proletariat.

Thanks to running a small-scale Shanghai perfume business (subsequently confiscated by the state), Qiu’s father — and his whole family — were branded as black and forced into circumscribed lives. According to Qiu, this outcome resulted despite his father being an “accidental capitalist,” who had been given some assets when his employer went bankrupt, assets that he subsequently tried to sell.

In 1966, at age 13, Qiu was forced to write the confession for his capitalist father, who was in the hospital recovering from eye surgery, and then to stand by him at his public humiliation as it was read aloud.

“My father had to be mass criticized, to stand on stage as a target, where people denounced him and chanted slogans for hours,” Qiu says.

Humiliating, yes, he says, but preferable to “being beaten to death by young Red Guards,” which was the fate of others. For Qiu himself, it was an odd and ironic first step in a writing career that would lead to novels that work to expose the historic brutality and ongoing corruption of the Chinese Communist Party. “The Red Guard’s approval of my father’s confession gave me some confidence in my writing,” Qiu says — though he admits it was “not quality criticism, just the Red Guard,” hardly the international literary critics who now praise his work.

Though ostensibly police procedurals dealing with mayhem and malfeasance — albeit laced with classical Chinese poetry and the wisdom of Confucius — the novels’ true subjects are Shanghai and the Communist Party.

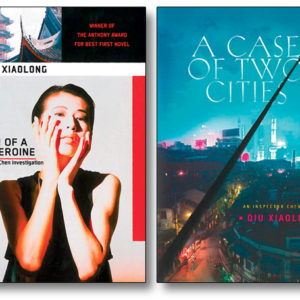

His lauded series of contemporary Shanghai crime novels — now being turned into feature films by a German/Australian/Chinese venture — feature Chief Inspector Chen Cao. Like Qiu, Chen works as a translator, writes poetry, and maintains an ambiguous relationship with the ruling party. Qiu’s debut novel, Death of a Red Heroine (2000), won the prestigious Anthony Award for best first novel by a mystery writer and was ranked as one of the five best political novels of all time by The Wall Street Journal. His eighth, The Enigma of China, will be released in the United States this spring by Minotaur Books. Qiu’s mysteries have been translated into some 20 languages, including French, German, Spanish, Italian, Russian, Polish, Danish, Swedish, Finnish, Hungarian, Dutch, Japanese, Norwegian, Greek, Hebrew, Slovak and Chinese. Original English versions are marketed in the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia, as well as the United States.

Though ostensibly police procedurals dealing with mayhem and malfeasance — albeit laced with classical Chinese poetry and the wisdom of Confucius — the novels’ true subjects are Shanghai and the Communist Party. Though in his heart he wishes to be a poet and literary scholar, Chen has been forced into police work by the party. Likewise, Qiu, who was on a similar scholarly path, made an abrupt turn into English-language crime fiction credited in large part to the 1989 Communist crackdown after the Tiananmen Square protests.

From accidental capitalist to accidental expatriate

“I came to St. Louis and Washington University in 1988 because of T.S. Eliot,” Qiu says.

“I came to St. Louis and Washington University in 1988 because of T.S. Eliot.”

—Qiu Xiaolong

A Ford Foundation exchange scholar, he had already translated The Waste Land, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock and other Eliot poems into Chinese. Qiu thought that his ongoing work on Eliot might be enriched by coming to the poet’s hometown and to the university founded by Eliot’s grandfather. He admits that translating Eliot into Chinese — poems difficult even for native English-speakers — can be daunting. “It requires very long notes,” Qiu says. “Sometimes the notes can be longer than the text.”

However, events in China worked to extend his stay in St. Louis. After the massacre of protesters at Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in early June 1989, party authorities cracked down on other protesters and their supporters in Beijing, Shanghai and elsewhere. That included Qiu, who had earlier written for the democratic movement. “I got in trouble with the government,” he says simply.

He figured it best not to return to China at that time, when those sympathetic to the protests were being purged from positions of authority and persecuted. So he made a life in St. Louis with his wife, Wang Lijun, and daughter, Julia Qiu, teaching, translating and earning his doctorate in comparative literature from Washington University in 1995.

Meanwhile, life back in China was changing dramatically. With the economy mushrooming and standard of living advancing, Qiu saw that the once-reviled capitalists had morphed into an honored class. He sought to chronicle those changes.

“I like mystery. Maybe I can use that as a framework, I told myself. It served my organizational purpose. And it is very easy for a cop to move around and ask questions and read documents others cannot.”

—Qiu Xiaolong

“My first book was meant to be about Chinese culture in this new age,” Qiu says. But as he sought a frame for the novel, he drew on his affection for mysteries and on the true crime stories he had encountered in his previous contacts with a Shanghai magazine.

“I like mystery. Maybe I can use that as a framework, I told myself,” Qiu says. “It served my organizational purpose. And it is very easy for a cop to move around and ask questions and read documents others cannot.”

He styled Chen as “a thinking cop and an intellectual, not just someone who finds out who did it,” Qiu says, “but also the cultural and social circumstances surrounding the crime.”

Mysteries with a message

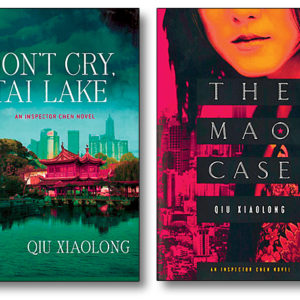

Those circumstances often involve the hard history of Communist China, as in Death of a Red Heroine and When Red Is Black (2004), which examine the tragic consequences of the Cultural Revolution. And they concern contemporary corruption, as in The Mao Case(2009) and his most recent, Don’t Cry, Tai Lake (2012), a novel focused on environmental contamination. His Inspector Chen novels give Qiu a way of understanding and accepting the past and present, he says.

“Like many others, I was resentful toward my parents for being ‘black’ — it meant that I didn’t have a future either, that I was not one of the politically correct class. I was traumatized, but my full understanding of the trauma came out gradually,” Qiu says. “Later, after many years, I saw that maybe one should do something to help change things. Yes, I use my books to settle scores, but never in a personal way.”

Poetry — both new and old — also plays a role in the Chen mysteries, with frequent allusions to classical Chinese poetry as well as original Qiu poems. Qiu has published a book of his own poetry, Lines Around China, and three books of translations: Evoking Tang: An Anthology of Classical Chinese Poetry, 100 Poems from Tang and Song Dynasties, and Chinese Love Poems.

“I wish I had more time for poetry,” Qiu admits, “but I am contented. I have Inspector Chen writing and quoting poetry, and thus am finding a larger audience for my poems.”

Qiu can now travel safely back and forth to China despite still being viewed with official suspicion. “I would never be trusted by the government,” he says. “My books are now being translated into Chinese but are heavily censored. Any political sentence they cut.” Government censors even obscured the Shanghai setting in several books by referring to it throughout as “H” and changing the names of streets and locales, Qiu says.

With his family and his fortunes now based in the West, Qiu remains headquartered in St. Louis. Nonetheless, he returns frequently to his beloved Shanghai, although with mixed feelings.

“I am happy to see living conditions improve for many people. Now there are not three generations squeezed into one room,” Qiu says. But he also sees the atrophy of the old Shanghai, with its crowed lanes, as depicted in his Years of Red Dust: Stories of Shanghai(2010) and Disappearing Shanghai, with photos by Howard W. French (2012; see sidebar at right).

He says the traditional way of life is vanishing, with its close human relationships. “A lot of consideration and comfort came from neighbors, people who shared many things,” he says. “But these are disappearing with the older houses.”

What also has disappeared is the denigration of capitalism and capitalists, who are now considered saviors of the new China.

“Ironic,” Qiu says. “All my father and my family suffered, for nothing — it’s the same government, same party.”

Rick Skwiot is a freelance writer whose latest novel is Key West Story; visit www.keyweststory.com.

For more on Qiu Xiaolong’s life and inspiration for writing mystery novels, visit YouTube at the following link.

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.