The audience roars with laughter. This is a good sign.

The roar grows louder. Even better.

Best of all comes a few beats later. Spinning on a dime, 600 middle-schoolers start shushing one another, impatient to get on with the story.

“There’s not an American in this country free until every one of us is free.”

—Jackie Robinson

January is not baseball weather, but this is St. Louis. Stan “The Man” Musial lies in state at the Cathedral Basilica. A few miles west, in a packed Edison Theatre, local students are learning about Jackie Robinson, the first African-American to play in the major leagues.

The occasion is Jackie and Me, a theatrical version of Dan Gutman’s acclaimed, time-traveling book. It is the fourth collaboration between the Edison Ovations Series, the university’s professional performing arts showcase, and Metro Theater Company, one of America’s finest theaters for young people and families.

“An important part of our mission is reaching out to the community and engaging people in conversation,” says Charlie Robin, executive director of Edison. “We try to highlight artists people otherwise wouldn’t see, and to provide experiences they otherwise wouldn’t have.

“Jackie and Me has it all,” Robin continues. “It’s about baseball; it’s about race; it’s about living history and growing up.

“With this one,” he adds, smiling, “we really hit a home run.”

The wonder of drama

“Jackie Robinson is an icon,” says director Tim Ocel, a lecturer in the Department of Music in Arts & Sciences. Yet dramatically speaking, this can be a mixed blessing — iconic deeds can overwhelm the knottier, more revealing parts of character.

“There was never a man in the game who could put mind and muscle together quicker and with better judgment than Robinson.”

—Branch Rickey

“But here we also see something of Jackie’s fears and anxieties,” Ocel continues. “We understand the injustices that Jackie and his wife, Rachel Robinson, were standing up to.”

And though the script has facts and drama, it also contains wonder and comedy, which teach lessons of their own.

“Laughter makes us vulnerable,” Ocel says. “To laugh is to acknowledge a genuine engagement. It disarms us and cracks open our souls.”

For a director, “laughter makes everything else come a little bit easier.”

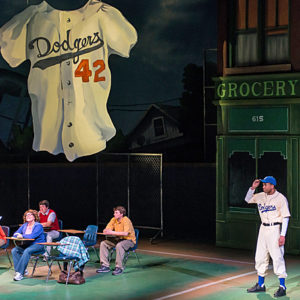

The story, adapted by Steven Dietz, centers on Joey Stoshack, a hot-headed young ballplayer (played by Kurt Hellerich) who allows himself to be goaded into a fight, costing his Little League team a game. Back at school, Joey is assigned to write a paper as part of African-American history month, and he chooses Robinson as his subject.

But Joey’s research will not take place in the school library. Instead, a rare baseball card magically transports him to the office of Branch Rickey, the Dodgers’ general manager, on the very day Rickey signs Robinson. He listens as Rickey (David Wassilak) warns about the challenges to come. He falls silent as Robinson (Reginald Pierce), at once ferocious and restrained, pledges to meet them.

All with one extraordinary twist: Joey, still played by Hellerich, is now perceived by the other characters to be black. “I don’t feel any different,” he muses to the audience.

“It’s a great device,” says Ocel, one that underscores essential arbitrariness of racism. “To step into the shoes of others is an amazing, frightening and often liberating event, and, coincidentally, it’s what the theater does best.

“Some have asked why the production doesn’t use an African-American actor to play Joey at this point, but if we did that, the soul of the character would be different,” Ocel adds. “The point of this twist is that the being of Joey stays the same, only the color of his skin changes.”

Art institutions make connections, fill gaps in education

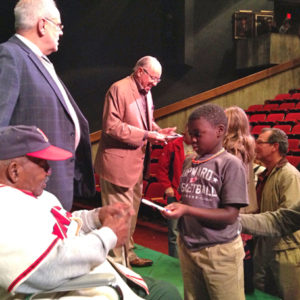

As with previous Metro collaborations, performances of Jackie and Me were evenly split between the general public and local school groups. In all, more than 4,000 students, ranging from third grade to high school, attended nine free weekday matinees.

Robin explains that, as city and state funding for field trips and other cultural outreach dries up, arts institutions are rising to fill the gap. For example, in addition to hosting performances, Edison recently launched a scholarship program to help districts pay the costs of transportation.

“Partly this is about growing the audience and introducing the next generation to the arts. But it’s also about expanding horizons.”

—Charlie Robin

“Partly this is about growing the audience and introducing the next generation to the arts,” Robin says. “But it’s also about expanding horizons.” While on campus, many school groups arrange additional visits with WUSTL students, faculty and facilities. “The idea is to leverage the full resources of the university.”

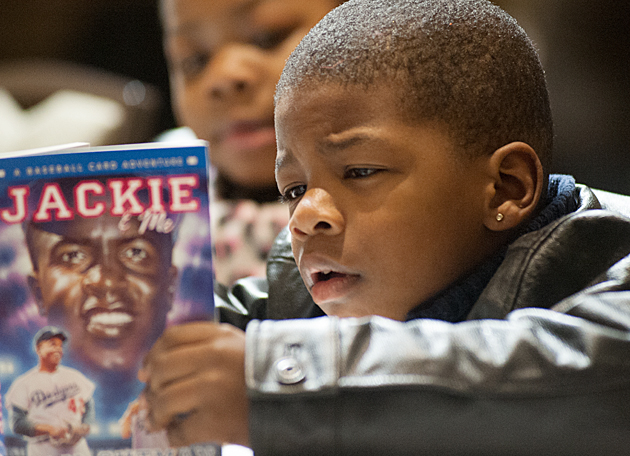

Amy O’Brien, program coordinator in the Institute for School Partnership (ISP), notes that, through its K-12 Connections* program, the ISP alone welcomed nearly 500 students, all from St. Louis and University City public schools. Of those, approximately 400 received copies of Gutman’s novel, which they were invited to compare and contrast to the theatrical adaptation. (*K-12 Connections is a partnership of the Community Service Office, the Institute for School Partnership, and the Department of Government and Community Relations.)

“We try to integrate the performance with other experiences,” O’Brien says. “And the students have been absolutely mesmerized — even when teachers worried that attention spans might wane.”

The honest thing

In one gut-wrenching sequence, an opposing manager hurls insults and, propping a bat to his shoulder, mimes a rifle shot. The audience gasps. Robinson responds with a hit. Then he steals a base. Then he steals another.

“Theater for young audiences is still theater. As a director, the approach doesn’t really change.”

—Tim Ocel

Suddenly, everything switches to slow motion. Six hundred middle-schoolers collectively hold their breath, savoring the moment as Jackie leaps to steal home. They erupt as Jackie wins the game.

“Theater for young audiences is still theater,” Ocel says, smiling. “As a director, the approach doesn’t really change. You don’t condescend. You don’t think ‘This is for kids,’ or ‘This is for adults.’ You just go from moment to moment and do the honest thing.

“It’s no different from directing Shakespeare,” Ocel concludes. “You do what is truthful. And you do it for everybody.”

Liam Otten is art news director in Public Affairs.

For more information, visit the following:

http://edisontheatre.wustl.edu/

http://metrotheatercompany.org/performances/public-performances/jackie-and-me/

http://schoolpartnership.wustl.edu/

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.