When strolling Washington University’s Danforth Campus, hundreds of eyes seem to take in your every step, every conversation. Perched on corners, above doorways and along windowsills, figures both bizarre and beautiful gaze down upon students, professors, staff and visitors. Many hold a hundred years of history, with much of it secret.

Do not call them gargoyles, although that is a first inclination. They are known as bosses or grotesques, having evolved long ago from the original “gargoylian” job of directing rainfall away from buildings and into the task of being purely decorative.

A return to Gothic style is signaled by the inclusion of such figures in the original Danforth Campus plans of Philadelphia architects Walter Cope and John Stewardson. Their liberal use also cemented ties with Cambridge and Oxford universities, whose campuses boast numerous bosses and grotesques.

The quest to understand the early 20th-century carvings is an informational scavenger hunt — a clue here, an insight there, and extra points if you can total up the number of figures. No one ever has, according to university archivists.

Many of the likely fascinating details of the original figures are hidden behind stone faces and sealed lips. Curious minds can only speculate. Local architectural stone carver Mike Gomez — whose work can be seen at Graham Chapel and the Danforth University Center — sees each grouping as telling a story that’s larger than any single figure. Many carvings represent the student-professor relationship and the often-difficult path toward completion of one’s education, Gomez says, adding that all are designed to “impart a message for the ages.”

From rhino to ram at Brookings

Since the initial construction of Washington University began in 1900, an unlikely pair of animals have presided over the Brookings Hall Quadrangle. The more menacing of the two, a rhinoceros-like creature with a chokehold on a horrified human, is one of 156 original sketches donated to University Archives in the mid-1980s by Fred R. Hammond, an architect with Jamieson and Spearl, who succeeded Cope and Stewardson. But the sketchbook offers no words — only pictures.

Gomez, whose carvings were informed by careful study of older images, provides interesting, if sometimes harsh, supposition: “The rhino is the professor, and the student just can’t get the lesson; therefore, the professor feels like strangling him,” Gomez posits. A second figure, a ram with a graduation hood, is the student, four years later. “Sometimes rams are hardheaded but now he’s got his book of knowledge,” Gomez surmises.

North Brookings’ beacon of wisdom

Mounted on a North Brookings Hall archway, this owl likely harks back to Roman mythology, according to a 2012 article in The Figure in the Carpet, published by the Center for the Humanities. The Romans correlated the wide-eyed bird’s ability to see at night with wisdom and its nocturnal wakefulness with vigilance. In 2007, this knowledge-seeking creature — with the addition of eyeglasses — became the Center for the Humanities’ logo, which in 2012 adopted a more modern look.

Surveying campus from Brookings–Cupples arch

Atop the Cupples 1–Brookings Hall archway, a dedicated surveyor has fixed his gaze toward the Cupples building for 114 years. The surveyor may have served as a reference to engineering, according to Michael Greenfield, JD, the George Alexander Madill Professor of Contracts and Commercial Law, who studied campus bosses and grotesques for the creation of new figures for Anheuser-Busch Hall. But no one seems to know for sure, and neither the farsighted figure nor his silent companion is talking.

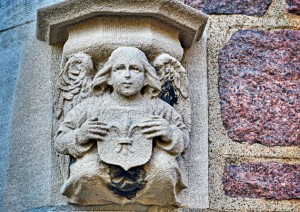

McMillan’s inspirational angels

When Jim Burmeister, involved with and director of Commencement for more than 40 years, arrived at Washington University, he was a young teenager whose part-time job administering entrance exams provided an early familiarity with some of the campus’ more fearsome figures.

But it was a contrasting image — one of a pair of angels resting on a McMillan Hall archway since 1906 — that comforted him during his long career on campus. “It just feels nice to me,” Burmeister says, but then quips, “but why it was put on the women’s dorm, I have no idea, because I’m sure they weren’t all angels living there.” According to Gomez, the architectural angels have another connotation: “They’re representative of thoughts having wings.”

Hideous carnivore haunting Graham Chapel

Few of the university’s grotesques and bosses are more gruesome than one in which a monster appears to be devouring a lamb over Graham Chapel, built in 1907. But Gomez offers the explanation that menacing creatures were thought to ward off evil spirits during the Middle Ages. So the image — one of more than 100 dotting the chapel — seems appropriate for a place of worship after all.

Graham’s gossiping grotesques

“It has ever been the privilege of Gothic designers to add thus a personal touch to their work.”

1910 Record

Figures flanking the Graham Chapel organ are unique for having been carved from wood rather than chiseled from stone. While some are rumored to have been constructed with the arrival of new organs in 1935 and 1948, a 1971 Washington Magazine article suggests the figures are the original designs of architect James P. Jamieson of Jamieson and Spearl.

Who can say what their secrets might be as their molecules reverberate to the music? Any and all conjecture seems in line with an unbylined 1910 Record article that asserts: “It has ever been the privilege of Gothic designers to add thus a personal touch to their work. The observer may find a meaning in each carved head and figure, a meaning which will change with his own mood.”

Wilson Hall’s anachronistic dinosaurs

A parade of dinosaurs embellishing the Wilson Hall entrance likely references its initial dedication in 1923 to the fields of geology and geography. But Esley Hamilton, a St. Louis County Parks architectural historian and adjunct professor in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, finds humor in these depictions.

“These [dinosaurs] are modern images,” notes Hamilton, explaining that no one in the Middle Ages would have understood what a dinosaur looked like. Even the early-1920s stonecutters likely had little to work with, as scientists had begun to speculate about the appearance of dinosaurs only a few decades earlier, in the mid-19th century.

Living legends at Anheuser-Busch Hall

Few figures resembling actual people adorn campus buildings. But a pair of likenesses on the east side of Anheuser-Busch Hall, completed in 1997, belong to a current law professor and a former dean. An image of Professor Michael Greenfield was dedicated to his more than eight years as building committee chair for the construction of the law building. A boss of the law school’s then-boss, Dean Dorsey D. Ellis Jr., JD, was added a short time later.

Three stages of student life at Danforth University Center

When Mike Gomez was asked to create figures for the Danforth University Center before it opened in 2008, he put his own personal spin on the newcomer-to-graduate theme with three images gracing the indoor courtyard. The first is a bear — the Washington University mascot — blithely enjoying an ice-cream cone, referencing the treat’s invention at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair.

The second is the ubiquitous owl, with a little branch growing out of what appears to be a dead stump, evidence of learning coming to life. What only the owl sees is Julius Caesar’s inscribed Latin declaration: “Veni, Vidi, Vici” (I came, I saw, I conquered).

The third figure, an angel, is the graduate, holding the holy grail — a diploma. “We take a student from being a neophyte, a partygoer, to beginning to be a serious student and then finally graduating and having wings to go out into the world,” Gomez says.

Nancy Fowler is a freelance writer based in St. Louis.