In their comments, the professors explored crisis leadership, relationship-building and flexibility. Several lamented that many of the accomplishments and attributes of their chosen presidents, ranging from the “Father of Our Country” to one who later fathered the modern Democratic party, are no longer valued.

Intelligence was also noted as a critical component of a good presidency. But according to one A&S professor, good luck is just as important as good reasoning ability when it comes to presidential legacies.

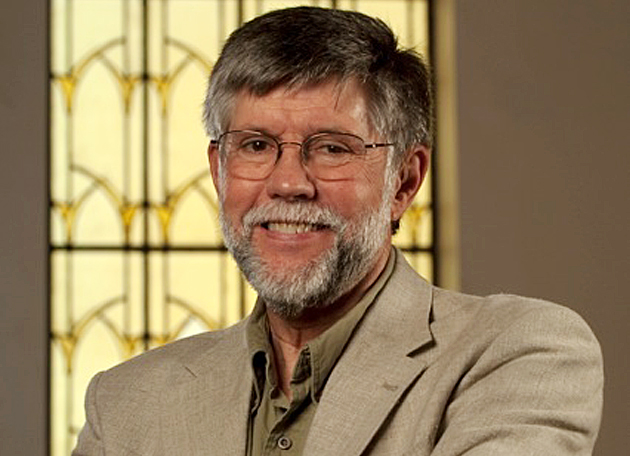

PETER KASTOR, PHD, PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY; PROFESSOR, AMERICAN CULTURE STUDIES PROGRAM

George Washington (1789–97) and James Madison (1809–17)

The presidents who initially held the nation’s highest office had no blueprint to follow as they led our country through its youth. Fortunately, President George Washington, the country’s first, was an excellent trailblazer, according to Peter Kastor.

“He could have made so many colossal errors — and he didn’t,” Kastor says. “His perceptiveness about what the institution could and should be was pitch-perfect.”

Washington broke new ground by setting precedents both small and grand: what to call the holder of the nation’s highest office (“Mr. President”), how many terms should a president hold (two), and who should make up the cabinet (advisers who are not also serving as legislators).

“If Washington symbolizes the president who rises to the occasion and often exceeds his own limitations, Madison stands as the cautionary tale of the limitations of the most talented presidents and of the office itself.”

— Peter Kastor, PhD

What’s most surprising about Washington’s sound decision-making? That he wasn’t the smartest guy in the room at the 1787 Constitutional Convention, Kastor asserts.

“Washington was not one of the great geniuses of the founding fathers,” Kastor says. “He certainly didn’t demonstrate the far-ranging intellect of men like Thomas Jefferson or Ben Franklin. But when faced with the challenge of the presidency, Washington not only demonstrated his skills but often exceeded his own limitations. I find that immensely impressive. Indeed, the ability to build off strengths and overcome limitations is among the skills we most value in our presidents.”

Twelve years after Washington left office, the Constitution’s principal author James Madison became the fourth president. It was Madison who had helped create both the powers and limitations of the presidency. Madison came into office with a wealth of experience that included service in Congress and eight years as Thomas Jefferson’s highly effective secretary of state. But despite his tremendous intellect and demonstrated skills, Madison was less successful than Washington, according to Kastor.

In straightforward political terms, Madison was theoretically a success story. He won two presidential elections by large electoral majorities, and his principal opposition (the Federalists) collapsed into insignificance during his tenure. And yet Kastor says that conflicts within his own party (the Democratic-Republicans), intractable diplomatic tensions, and Madison’s own inability to realize the limitations of the federal system he had helped to create undermined his administration. Madison’s presidency is best known for the War of 1812, an ill-conceived and poorly executed venture launched by the United States at Madison’s urging. Most importantly, Madison overestimated the federal government’s capacity to organize for war and his own ability to supervise that war.

“I’ve always found Washington and Madison fascinating not just for what they achieved but also what they teach us about the presidency,” Kastor says. “If Washington symbolizes the president who rises to the occasion and often exceeds his own limitations, Madison stands as the cautionary tale of the limitations of the most talented presidents and of the office itself.” Together, they demonstrate how abilities and circumstances intersect to shape the successes and failures of a presidency.

WAYNE FIELDS, PHD, LYNNE COOPER HARVEY DISTINGUISHED PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH, AMERICAN LITERATURE, AND AMERICAN CULTURE STUDIES

Abraham Lincoln (1861–65)

Known for both his intellect and his success, 16th President Abraham Lincoln presided over our nation’s most divisive period: the secession of the Southern states and the Civil War. Despite the split, Lincoln maintained the notion of national unity, according to Fields.

“He did this not simply through the executive policies and the way in which he administered the job but also through the considerable amount of care with which he crafted his words and the speeches,” Fields says.

Three speeches illustrate the evolution of Lincoln’s thinking even as his commitment to one nation stood firm. Before the Civil War, in his first inaugural address, Lincoln resolved to keep the North and South together. During the war, in his famed Gettysburg Address, he noted the importance of fighting for the principal of equality. After the war, and during his second inaugural, he explained why the North suffered so much death when it was fighting for equality — for good — while the South fought for slavery.

But like his time on Earth, the lessons of Lincoln are in some ways short-lived. The ability to shift positions after taking in new information is too often seen as “flip-flopping” in today’s political arena.

— Wayne Fields, PhD

“The first assertion is that we are one people, North and South, and the second assertion is that we are one people, black and white,” Fields says.

As for the third? “That’s the ultimate proof that we are one in the eyes of God, that he suffered the judgment on the entire nation, not half the nation,” Fields says.

Lincoln’s ability to evolve in his thinking was one of his great strengths and is illustrated by his eventual embrace of racial equality.

“He did not come into the office without failings in the area of racial attitudes,” Fields says.

Had assassination not frozen Lincoln’s legacy in his second term, it would have been interesting to witness his leadership following slavery’s demise, according to Fields. In an era when Southern whites secured their domination through segregation and disenfranchising black voters, Lincoln might have made a difference.

“The process might have been helped by some of his political savvy and strength,” Fields says.

But like his time on Earth, the lessons of Lincoln are in some ways short-lived, Fields says. The ability to shift positions after taking in new information is too often seen as “flip-flopping” in today’s political arena.

“Present politics makes that a liability, a lack of commitment. So even if something is proven to be wrong, we keep repeating it as truth,” Fields opines.

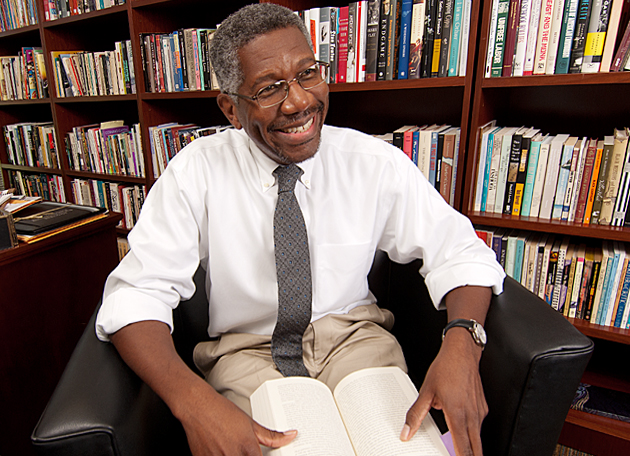

GERALD EARLY, PHD, MERLE KLING PROFESSOR OF MODERN LETTERS; DIRECTOR, CENTER FOR THE HUMANITIES

Theodore Roosevelt (1901–09)

As the Reconstruction years reinforced the notion of so-called separate-but-equal racial policies, black leaders were hard-pressed to make their arguments to top-level leaders. But the office-holder chosen by Gerald Early — 26th President Theodore Roosevelt — risked his reputation to befriend Booker T. Washington, an author and educator born into slavery.

At 42, Roosevelt was the youngest president and the first to take office in the 20th century, following the assassination of William McKinley. Having already established a relationship with Washington during visits to Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, Roosevelt asked Washington to visit him on his turf.

But the office-holder chosen by Gerald Early — 26th President Theodore Roosevelt — risked his reputation to befriend Booker T. Washington, an author and educator born into slavery.

“It was the first time a black person was ever invited to the White House to have dinner,” Early says. “Roosevelt got a lot of criticism for doing it, especially in the South.”

Roosevelt was not immune to that backlash, and while he wanted to maintain the friendship, he also pushed Washington away.

Then came a tragedy known as the Brownsville Affair. In 1906, African-American soldiers were accused in the fatal shooting of a white man in the town of Brownsville, Texas, where they were stationed.

Roosevelt believed the men were guilty; Washington, like most African-Americans, did not. At the cost of his own influence with other blacks, Washington maintained the friendship with Roosevelt, despite their differences.

“Washington felt that if he came out against the president, he would lose the relationship, which he felt was important not just for himself but for the group,” Early says.

Their camaraderie served as a model for future presidents as the civil rights movement developed.

“It was a forerunner to the relationship that Franklin Roosevelt would have with Walter White, who was head of the NAACP in the 1930s, or the relationship that both President Johnson and President Kennedy would develop with Martin Luther King Jr.,” Early asserts.

Ironically, according to Early, black leaders may have less access to the nation’s first black president, Barack Obama.

“He has overwhelming support from African-Americans, but because he’s African-American, he feels he can’t afford to reach out to them as much as he would like to,” Early says.

CLARISSA RILE HAYWARD, PHD, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF POLITICAL SCIENCE

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1933–45)

As our 44th president finishes up a term that will become known as his first or his only, Clarissa Rile Hayward points to 32nd President Franklin Delano Roosevelt — fifth cousin of Theodore — as the most interesting.

“I find Roosevelt’s particular strengths and accomplishments so far from where we are now in our current politics,” Hayward says.

“I find Roosevelt’s particular strengths and accomplishments so far from where we are now in our current politics.”

— Clarissa Hayward, PhD

Faced with pulling our nation out of the Great Depression, FDR initiated the creation of numerous government agencies: the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), Federal Housing Administration (FHA), the Social Security Board and the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), among others.

“These and other major New Deal agencies regulated business, providing a safety net that protected us from the worst excesses of capitalism; protected the rights of workers to organize unions and participate in collective bargaining; and provided jobs for unemployed people,” Hayward notes.

Roosevelt’s reforms transformed the Democrats into champions of the poor and underprivileged, anointing him as the father of the party as it looks today.

Roosevelt’s vision for the Democratic Party platform and many of his institutions have endured. Social Security, while under siege, still provides retirement income for millions. The New Deal’s FHA is responsible for our current robust numbers for home ownership.

But today, the national pendulum is swinging away from government-as-caretaker. The concept of freedom has come to mean freedom from government regulation, according to Hayward.

“When government does not regulate markets, when it does not limit how corporations can use their power, it doesn’t make us free; it makes us subject to rule by big business,” Hayward surmises. “And I think being subject to rule by big business is the antithesis of democracy, because big business is not accountable to the people in the way elected government is.”

Nancy Fowler is a freelance writer based in St. Louis.

Comments and respectful dialogue are encouraged, but content will be moderated. Please, no personal attacks, obscenity or profanity, selling of commercial products, or endorsements of political candidates or positions. We reserve the right to remove any inappropriate comments. We also cannot address individual medical concerns or provide medical advice in this forum.