Alex S. Evers, M.D., wears a number of hats. He is the Henry E. Mallinckrodt Professor and head of the Department of Anesthesiology and a professor of medicine and of molecular biology and pharmacology. He also chairs the board of directors for the Washington University Faculty Practice Plan.

He’s been at the University since 1983, when he was an assistant professor in anesthesiology, an instructor in medicine and a research fellow in the Department of Pharmacology. A lot of things have changed since then, and the differences in his titles are only the tip of the iceberg.

Back then, William Owens, M.D., led the relatively new anesthesiology department and its 14 faculty members. Today there are 90.

In the early ’80s, the department had no research program. Now it houses the second-biggest anesthesiology research program in the country, and when experts rate the department, it consistently ranks in the nation’s top 10.

Even though Evers doesn’t take credit for all the progress, which he says started when Owens was leading the department, he’s proud that the department has grown considerably.

Evers says that growth is one of the most satisfying parts of his job — in a field he almost didn’t enter.

When he was in medical school, he enjoyed anesthesiology, but some of his advisers thought choosing it as a specialty would be a bad career move. He followed their advice and didn’t go into anesthesiology until after medical school at New York University.

“Not a lot of people were doing it then,” Evers says. “Some of my advisers didn’t think it was a good career move, so I went into internal medicine instead and actually practiced internal medicine briefly, but that wasn’t really what I wanted to do.

“My dream job in those days was to have the opportunity to run an intensive care unit at an academic hospital.”

He was drawn to acute medicine, and he wanted to work in intensive care, so eventually Evers decided to follow his heart and continue his training in anesthesiology.

After completing a residency in anesthesia and a fellowship in surgical intensive care at Massachusetts General Hospital, Evers came to St. Louis to work in the surgical intensive care unit at Barnes Hospital. By 1986, he was the unit’s medical director — a job he kept for a decade.

But what convinced Evers to come to St. Louis and Washington University was the opportunity to train in the laboratory of Philip Needleman, Ph.D., now an adjunct professor of molecular biology and pharmacology.

In the early ’80s, Needleman was doing work that would eventually lead to his discovery of a second cyclooxygenase enzyme (COX-2) — making possible the development COX-2 inhibitors, such as Celebrex, as treatments for inflammatory diseases like arthritis.

“I came here to work with Phil Needleman,” Evers says. “I was very inspired by him. It was Phil and Dave Kipnis, the former head of medicine, who infused me with the idea that this was a fabulous academic institution and a great place to train.

“They also convinced me that Bill Owens had a vision for creating a premier anesthesia department here and that I would be getting in on the ground floor.”

Evers didn’t help Needleman find the COX-2 receptor, but he did learn about inflammation.

He began studying how lipids (fats) influence inflammation. That led him to look at how lipid agents act on inflammatory cells and on cells in the nervous system, learning how those interactions could influence the mechanisms of anesthesia.

Most of Evers’ career has involved looking at how lipid-like drugs can be used in anesthesia. For the past several years, he has focused on a particular class of lipid-like drugs: steroids.

Opening the ‘black box’

During the last two decades, his department is not the only thing that has changed in the world of anesthesiology.

“When I got into this field, much of anesthesiology was a ‘black box,'” Evers says. “We knew these drugs worked, but we didn’t have a clue why or how.”

But increased study of the mechanisms of anesthesia has revealed the systems through which many of the drugs exert their effects.

In anesthesia, drugs such as nitrous oxide and ketamine work by inhibiting excitatory communication between nerve cells. Other anesthetics work — mainly at nerve terminal proteins called GABA receptors — by increasing inhibition of the central nervous system.

The targets where drugs interact with cells also are better understood. And Evers helps illuminate those targets, literally.

“The technique is called photo-labeling,” he says. “We take tissue from the brain and incubate it with a steroid. Then we shine light at a specific wavelength, and it causes the molecules in the drug to bind to the molecules in the cell.

“Then separation techniques and mass spectrometry help us identify the specific parts of proteins with which the drugs interact.”

The work is part of a National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant to study the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which anesthetics produce their effects. Evers studies steroids with Douglas F. Covey, Ph.D., professor of molecular biology and pharmacology in the Division of Bioorganic Chemistry.

“Doug is a synthetic steroid chemist,” Evers says. “So Doug makes them, and then I do the analysis.”

The two met back when Evers was a fellow in Needleman’s lab. Covey recalls an Evers study that found rats were more sensitive to anesthetic drugs when they were placed on a diet deficient in fatty acids.

Covey was interested because he was working with anticonvulsant drugs at the time, and although they were studying different types of drugs, they were interested in the same set of molecular interactions, involving GABA receptors and enhanced inhibition. The current collaboration with steroid anesthetics involves that same class of receptors.

“Alex is all I could hope for in a colleague: smart, dedicated and a pleasure to work with,” Covey says. “He also frequently brings a smile.

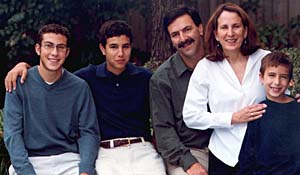

“At a recent faculty dinner, I noticed that he was wearing a necktie with a repeated pattern of the Washington University shield interspersed with a series of z’s, which probably is appropriate for the head of an anesthesiology department.” (See tie in photo above.)

He wrote the book

|

Alex S. Evers Born: June 15, 1952, in New York City University positions: Henry E. Mallinckrodt Professor of Anesthesiology, professor of medicine, professor of molecular biology and pharmacology and head of the Department of Anesthesiology Family: Wife, Carol Evers, M.D.; children, Sam, 20; Jacob, 18 (both undergraduates at Yale University); Joseph, 12. Parents, Leo, 87, and Irma, 82 (both live in Yonkers, N.Y.); and two sisters, Kathie, a radiologist in Philadelphia; and Sally, who lives in Mayaguez, Puerto Rico. Hobbies: Bicycling, running, swimming and fishing. He’s also a baseball fan who happened to be at Yankee Stadium to see Roger Maris hit his 61st home run to break Babe Ruth’s record and at Busch Stadium to see Mark McGwire hit his 62nd home run to break Maris’ record. He’s also an avid reader of history, especially Middle Eastern and African history. |

Evers has authored dozens of scientific papers about his research, but this month he has a different kind of publication being released: a textbook titled *Anesthetic Pharmacology: Physiologic Principals and Clinical Practice*. He edited the 1,000-page book with Mervyn Maze, M.D., the Sir Ivan Magill Professor of Anaesthetics and Intensive Care and chair of that department at Imperial College in London.

It covers all the drugs anesthesiologists might use or encounter and discusses what’s known about how the drugs work and how they are used in clinical practice.

“Alex convinced me that by participating in this venture, we would be putting something back into our discipline,” Maze says. “He also conveyed a sense of calm even when we were behind schedule and especially when we had thorny issues to address, and I found his dependability inspiring.

“In the words of my grandmother, he is a ‘chochom’ — which means he’s smart — and a ‘mensch.’ That means he’s a stand-up guy.”

He’s also a baseball fan, bicyclist, runner, swimmer and fisherman. He’s a family man, too. Evers and his wife, Carol, an internist in private practice, have three sons.

He tries to take the boys to a nice fishing spot every year. They went fly-fishing for stripers in Massachusetts last summer. They’ve also been to Alaska.

But most of his travel is job-related — for lectures, meetings and reviews of anesthesia departments.

“What’s fun about my job is that I have an opportunity to be involved at the highest level of what’s going on scientifically and have the excitement of discovery,” he says. “I’m also involved with health policy and clinical delivery.

“I get to do it all. That’s the best thing about my job. It’s also the worst because it’s so hard to do it all well.”

Even though Evers’ job requires him to juggle a number of hats, he wears them all well.