Peanut butter could save the world. If Mark J. Manary, M.D., has his way, that ooey, gooey lunchbox staple might be some kids’ best hope for the future.

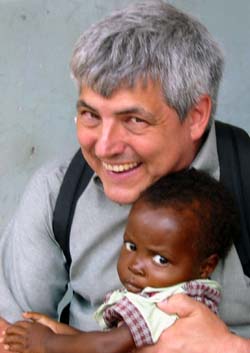

Manary, associate professor of pediatrics, started a program two years ago that has saved hundreds of starving children in one of the poorest countries in southern Africa. And some day, the Peanut Butter Project could benefit millions of children in the developing world.

“Optimism is very powerful,” Manary says. “If you believe that something’s possible, you will put your heart and soul in it and try it. And sometimes, it will work out.”

Manary first visited Africa in 1985 and returned a second time almost a decade later as a Fulbright Scholar at the University of Malawi’s College of Medicine. When he arrived, the pediatrics chief at the medical school advised him to pick a specialty but warned him of the pitfalls of tackling malnutrition.

He told Manary the ward was a mess, kids seemed to die very frequently and doctors didn’t know why. But Manary has always liked a challenge and a chance to make things better.

At the university’s hospital, Manary and his staff added large amounts of potassium to children’s diets, decreasing the hospital’s case fatality rate from 40 percent to 10 percent.

In Malawi, a country about the size of Kentucky and mostly made up of poor farmers, more than half the children are chronically malnourished, and one in eight children die because they don’t get enough to eat. Each year, tens of thousands of kids are sent to inpatient feeding centers — established solely for the treatment of starving children — where they are fed milk diets for weeks.

Only 25 percent fully recover.

After his experience at the University of Malawi’s College of Medicine, Manary knew he wanted to study severe malnutrition and return to that country. He now treks there several times a year, sometimes with his wife, Mardi, and his children, Megan, 16, and Micah, 14.

Health-care workers in Malawi believed starving children needed to take nutritious food home from the hospital. After consulting a French nutritionist who was developing peanut butter recipes, Manary launched the Peanut Butter Project in 2001.

As part of it, some of the children discharged from the country’s largest hospital took home a peanut butter mixture to eat three times a day for five weeks. The conveniently packaged mixture included peanut butter, vitamins, minerals, sugar and vegetable oil. As part of this project, they also were discharged from the hospital sooner than usual — after days instead of weeks. Manary had discovered that children recover more quickly at home.

An amazing 95 percent of the children who ate the peanut butter mixture fully recovered, reaching 100 percent of their weight for their heights. Only 1 percent of the group died.

“I said, ‘Wow, this is really working!'” Manary says.

The Peanut Butter Project, which is sometimes called home-based therapy, enrolled 1,000 children in the first two years. Last year, with the help of medical student Heidi Sandige, about 3,000 children participated in the Peanut Butter Project.

This year, Manary expects more than 7,000 will be involved.

The peanut butter concoction is produced and packaged in Malawi. Over the years, the project has received funding from the Allen Foundation; the Children’s Hospital Foundation; William H. Danforth, chancellor emeritus and vice chairman of the University’s Board of Trustees; Valid International; and local community groups.

“This year, we’re going to continue the project through the local Malawian institutions — they themselves are going to manage and take care of the kids,” Manary says. “When everything is running smoothly, we hope to scale it up to something that can be used all over the country.”

Most children in Malawi don’t become malnourished until they’re between 6-30 months old — the time frame in which breastfeeding stops. Because food is scarce, most families eat just once or twice a day, gathering around a pot and grabbing pieces of a corn mixture.

“This isn’t enough, and that’s why they fall into this pit of malnutrition,” Manary says.

Finding something for mothers to feed their children at 6 months of age is one of the most important problems in global nutrition today, Manary says. That’s where his ready-to-use peanut butter food comes into play.

Always helping

Manary and his wife, a parish nurse at Gethsemane Lutheran Church in St. Louis, have always helped the less fortunate.

When he finished his pediatric training in 1985, they decided to work at a mission hospital in Tanzania. Upon returning to the United States two years later, they provided medical care at an Indian reservation in South Dakota.

“I’ve always been an activist for causes and changes that I think are going to make life better for people,” Manary says.

The oldest child of a traveling auto-parts salesman and an English teacher, Manary and his two sisters grew up in Michigan and the New York City area. He says his family didn’t travel much, and that he was the odd one out in trying to change the world.

In high school, Manary started a club to promote recycling and established an Earth Day in his hometown. He also was active in the anti-Vietnam War movement.

He majored in chemical engineering and chemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, planning to become a scientist. Students there were able to choose an elective in which they could study whatever they wanted. Many chose to work in a laboratory, but Manary organized students to go into tenements in Boston and help families overwhelmed by substance abuse.

After college, Manary took an engineering job with a company in St. Louis that produced huge pieces of aluminum called ingots.

Unexpectedly, the School of Medicine contacted him because of his undergraduate academic achievements. He took another leap of faith and decided to give it a try in 1978.

Medical school initially was difficult for Manary because he had no training in biology and wasn’t used to memorization. He chose to specialize in pediatrics because children usually get better.

In 1989, Manary was hired as an instructor in pediatrics in the Division of Emergency Medicine. “It is a good fit for me personally,” Manary says. “I enjoy the intellectual challenge of figuring out what the problem is, and I also like helping families in crisis. The helper in me wants to meet people in a moment of need and provide something for them.”

Robert Kennedy, M.D., associate professor of pediatrics and one of his colleagues in the emergency department, says Manary is an intriguing physician and person who holds his highest admiration.

“Mark has not only managed to become intimately aware of the medical struggles that many children face in developing economies, but he has also worked hard throughout his career to find answers to basic health questions that have a tremendous impact on their daily lives,” Kennedy says. “In the process, he has developed a world view that most of us can only admire.”

Manary also teaches nutrition courses to second-year medical students and nutrition electives to fourth-year medical students.

|

Mark J. Manary Born: April 5, 1956, in Bay City, Mich. Family: Wife, Mardi; children, Megan, 16; Micah, 14 Degrees: B.S. 1977, chemistry and chemical engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; M.D. 1982, Washington University School of Medicine |

Sandige, who spent last year working with Manary as part of a Doris Duke Clinical Research Fellowship, describes him as a team player who makes everyone feel appreciated.

“He has this amazing quality of every now and then stepping back and saying, ‘Thank you, you’re very important to this project. This couldn’t go on without you,'” she says.

Last year, Manary and his team conducted a small project in which 6-month-olds in Malawi were fed the peanut butter mixture to see if malnutrition could be prevented. The results were promising.

André Briend, M.D., Ph.D., a nutritionist who works for a French health institute, believes Manary’s work will change the way children in the developing world are fed. He recently went to a meeting in Dublin, Ireland, attended by 70 experts on the treatment of severe malnutrition from either the academic world or major United Nations or nongovernmental aid agencies.

“The whole meeting was about home-based therapy, and the idea obviously is gaining more and more attention and having major practical implications,” Briend says.

Manary’s colleague James P. Keating, M.D., the W. McKim O. Marriott, M.D., Professor of Pediatrics, adds: “Mark is a man of solid intelligence with hard-earned skills who always has taken responsibility for those with less power than himself. What the folks who know his work consider courage and dedication is ‘just doing his job’ to him.

“He has combined the power of the scientific method with the humanity and humility of the biblical Good Samaritan in his work in Malawi.”