A piece of literary history has returned to Washington University in St. Louis, thanks to a fortuitous find in a New Orleans bookstore.

The story begins in February 2004, when Henry I. Schvey, Ph.D., professor and chair of the Performing Arts Department in Arts & Sciences at Washington University, directed (with Shelley Orr) the world premiere of “Me, Vashya,” a one-act play written in 1937 by then-student Tennessee Williams, as part of an international symposium on Williams’ early career.

“Me, Vashya,” which remains unpublished, famously placed fourth in a campus playwriting contest — a bitter disappointment to the young playwright, who stormed into his professor’s office before storming out of St. Louis altogether, expunging the play from his list of works and Washington University from his 1975 “Memoirs.”

Yet the reception of “Me, Vashya” was not the only factor in Williams’ decision to leave Washington University. As biographer Lyle Leverich reports in “Tom: The Unknown Tennessee Williams” (1995), the playwright was deeply concerned about his upcoming final examination in Greek.

In a May 30, 1937, journal entry, Williams complains of “Blue devils all this morning” and concludes, “Tomorrow Greek final which I will undoubtedly flunk.”

Schvey — visiting New Orleans only weeks after “Me, Vashya’s” debut to deliver a paper at the 2004 Tennessee Williams Scholars’ Conference — was of course familiar with this background. He was thus perhaps uniquely qualified to recognize the significance of a small blue test booklet he found while perusing a collection of rare Williams-related materials at Faulkner House Books, a prominent French Quarter bookstore.

“I knew instantly what it was,” Schvey said of the booklet. “It was his Greek exam.”

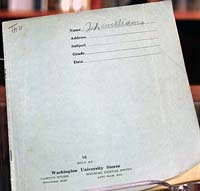

Schvey explains that the booklet, which closely resembles those still used by students today, is plainly labeled as being sold by the “Washington University Stores” and bears the name “Th. Williams” — significant in that Williams did not adopt the nickname “Tennessee” until several years after leaving St. Louis.

Inside, Schvey found a series of Greek-to-English and English-to-Greek translations, with individual grades for each exam section: A-, C , C-, D and D. More startlingly, he also found a 17-line, pencil-written poem. Still visible is an initial title, “Sad Song,” which Williams lightly erased and replaced with the more contextually appropriate “Blue Song” — a witty double-reference to the author’s mood and medium.

“The poem was presumably written at the time of the examination,” Schvey noted, adding that, as far as he has been able to determine, “Blue Song” has never been published and, indeed, was entirely unknown to Williams scholars.

“It is clearly the work of a young man who doesn’t know his next move in life,” Schvey continued. “Williams always felt uprooted in St. Louis, a feeling he describes here in very lyrical terms, in lines like ‘If you should meet me upon a/ street do not question me for/ I can tell you only my name/ and the name of the town I was/ born in … .’ I found it very moving.”

Williams’ poetry has long been overshadowed by his dramatic output, which includes roughly three-dozen full-length plays, 70 one-acts and five screenplays. (He also wrote two novels and several hundred short stories). Yet Williams wrote poetry all his life. In 1944, he was included in the anthology “Five Young American Poets” and he later published two solo collections, “In the Winter of Cities” (1956) and “Androgyne, Mon Amour” (1977).

“Williams was very dedicated as a poet,” said Allean Hale, adjunct professor of theater at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, who has written extensively about Williams’ early years. As a young man, “He actually thought of himself primarily as a poet, rather than as a playwright, until he began working with the Mummers of St. Louis, a local theatre group that produced Williams’ “Headlines” in 1936, followed by “Candles to the Sun” and “Fugitive Kind” in 1937.

Schvey quickly alerted Anne Posega, head of the university’s Olin Library Special Collections, to his discovery. Posega in turn arranged for Special Collections, which also houses the “Me, Vashya” manuscript, to purchase the booklet.

(In an interesting coincidence, Special Collections also recently received a substantial gift of Williams-related publications — including signed first editions, foreign language editions, critical monographs, biographies, interviews and other materials — from Fred W. Todd, a Williams scholar based in San Antonio.)

Schvey, meanwhile, is thrilled that the “blue” booklet has returned to campus.

“The booklet is a significant artifact of Williams’ life in St. Louis, while the poem reflects a period of great anxiety and tribulation,” Schvey concluded. “Bringing it back to St. Louis and to Washington University — in a way, things have come full circle.”