When he was young, Bruce D. Lindsay, M.D., associate professor of medicine, liked to wrestle. Back then, his opponents were scrappy kids from Haddonfield, N. J., bent on proving their worth.

Today, the stakes are higher for Lindsay, but the characteristics of a good wrestler — intelligence, action and especially perseverance — are clear in his accomplishments.

Like many high school students, academics often took a back seat to having a good time for Lindsay.

“I never dreamt I’d go to medical school,” he says. “I think some of my teachers would be surprised at what I’m doing now.”

But once he was in college, Lindsay developed a long-term vision of where he wanted to be and stayed the course even when things weren’t easy. Midway through his freshman year at Eckerd College, a liberal arts school in St. Petersburg, Fla., he decided to study medicine.

He graduated from Jefferson Medical College in 1977 and completed a residency at the University of Michigan. To pay back his scholarship obligations to the National Health Service Corps, the agency assigned him to an internal medicine practice for three years in East Jordan, Mich., a rural town in the northern part of the state.

Treating patients there showed him how little was known about arrhythmias, or abnormalities in the electrical currents that allow the heart to beat.

People with this condition experience racing hearts, and they often feel as if they’re going to pass out. All arrhythmias are not life threatening, but they can greatly affect patients’ lives, spurring many trips to doctors’ offices and emergency departments.

“I would call the nearest cardiologist, who was about 40 miles away, but they didn’t know how to treat these patients either,” Lindsay says. “They weren’t bad cardiologists — it was just where the field stood in 1980.”

Lindsay decided to pursue a fellowship in cardiology and study arrhythmias, landing at Washington University School of Medicine in 1983. Today, he is an expert on the subject.

“He is a superb clinician and highly respected at national and international levels as an authority on heart-rhythm abnormalities and their treatment,” says Michael E. Cain, M.D., the Tobias and Hortense Lewin Professor of Cardiovascular Disease in Medicine, who trained Lindsay. “He’s dedicated to his work and is someone who constantly tries to achieve excellence.”

Matters of the heart

Arrhythmias fall into two main categories: ventricular and supra-ventricular. Supraventricular arrhythmias occur in the heart’s two upper chambers — the atrium. Ventricular arrhythmias happen in the heart’s two lower chambers — the ventricles — and can lead to sudden death.

Since Lindsay began studying arrhythmias, major changes have occurred in their treatment. Previously, patients were treated solely with medications that required a large degree of trial and error. Also, many patients couldn’t tolerate the medications very well.

When Lindsay was practicing in Michigan, the New England Journal of Medicine published an article about the first use of an implantable defibrillator in a patient who had a ventricular arrhythmia.

“I thought it was a very novel idea,” Lindsay says. “But I never expected to meet the people who did the work, who I ultimately got to know, and I never expected to be putting those in patients.”

During a sabbatical years later at Newark Beth Israel Hospital, Lindsay worked with Victor Parsonnet, M.D., and Sanjeev Saksena, M.D., who were studying the feasibility of implanting a defibrillator without opening a patient’s chest. Their preliminary research in this area helped develop a technique used today to implant cardiac defibrillators.

“There’s been a striking change in survival rates as we’ve had these defibrillators implanted in people,” Lindsay says. “Now we can implant a defibrillator and send people home. If they get more arrhythmias, we may need to put them on medications, but they won’t necessarily have to come into the hospital.”

Treating arrhythmias with ablation — being able to pinpoint where they’re coming from and using a catheter to destroy them with radiofrequency energy — also has greatly altered the field. And the School of Medicine was one of the first places in the country to do these procedures.

Mitchell N. Faddis, M.D, assistant professor of medicine, who trained under Lindsay and has worked with him since 1998 on the Clinical Cardiac Electrophysiology Service, calls Lindsay an excellent teacher, a great role model and a gifted clinician.

“I have worked with Bruce on a variety of new treatment strategies for atrial fibrillation,” he says. “In spite of his clinical and administrative responsibilities, Bruce has remained committed to advancing the field of cardiac electrophysiology through his research efforts.”

Lindsay has worked with Steretotaxis Inc. to develop the Magnetic Navigation System (MNS), which enables heart-rhythm experts to use magnetic fields to guide catheters to treat arrhythmias.

|

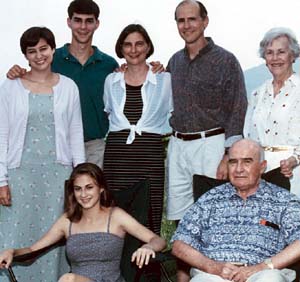

Bruce D. Lindsay Years at the University: 22 years Hometown: Haddonfield, N.J. University titles: Director of Clinical Electrophysiology Laboratory and associate professor of medicine in the Division of Cardiology Family: Wife, Elizabeth, and children, Shane, 26; Dana, 24; and Marcia, 21 Hobbies: Spending time with his family and hiking in national parks |

Andrew F. Hall, now director of research collaboration for Siemens Medical Solutions, AX Division, worked with Lindsay for seven years to develop the Magnetic Navigation System. Hall, like many of Lindsay’s colleagues, was struck by his perseverance.

“There were times when I wasn’t sure this was going to work, but he kept trying,” Hall says. “I think a lot of physicians would have said, ‘I don’t think I can continue with this,’ but he stuck with it through thick and thin.”

Lindsay also holds national leadership positions in the American College of Cardiology and the Heart Rhythm Society.

In these positions, he has helped develop new health-care policy, such as the expansion of Medicare coverage for patients who receive an implantable cardiac defibrillator to prevent sudden death.

“I’ve come to appreciate that the professional organizations do a great deal to help improve the quality of our practices, through education, supporting research and advocacy,” Lindsay says.

“We have to stand up for ourselves, challenging insurance companies and making sure government policies take into consideration things that are important to us and to our patients.”

Balancing act

Balancing his time is his greatest challenge, Lindsay says. And he attributes much of his success to the support of his wife, Elizabeth, a math teacher at Chaminade College Prepatory School.

When they do get away for vacation, they like to hike and have been to most of the national parks. Last year, they explored Olympia National Park.

They also have three children. Shane, 26, is a marriage and family counselor in Louisville, Ky.; Dana, 24, is a Spanish teacher in a magnet school in New York City; and Marcia, 21, is an international politics major at Illinois Wesleyan University in Bloomington, Ill.

When Lindsay came to St. Louis in 1983 for his cardiology fellowship, he thought he would move on after three years. But it turned out to be a great environment for him and his family, and he feels lucky to have had the opportunities he’s had.

“Witnessing all the changes in the treatment of arrhythmias is one of the things that has kept me here,” Lindsay says. “It seems as if no year is exactly like the other one. We’re always changing how we do things and finding better ways to do it, and it’s fun to be on the cutting edge.”