Mice infected with a bacterium related to the plague sharply increase production of an enzyme that makes the inflammatory hormone histamine, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found.

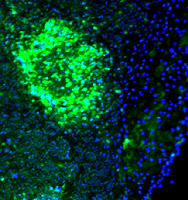

The increase, which occurs in intestinal structures known as Peyer’s patches, appears to be an important part of the mouse’s successful efforts to control the infection. But the size of the increase also has researchers wondering if the bacterium, Yersinia enterocolitica, might have something to gain from higher histamine levels or the inflammation they cause.

“We don’t have solid comparative data yet for the histamine response triggered by other pathogens, and the host does appear to benefit from the increased histamine,” notes lead author Scott Handley, a graduate student. “But that doesn’t mean there isn’t a beneficial effect for Yersinia that we’re just not seeing yet.”

In addition, the finding reinforces a longstanding suspicion that some heartburn and gastric reflux medications may increase susceptibility to infections. Some of those medications block a histamine receptor that scientists found was important to the mouse’s ability to resist Yersinia infection.

“The data shouldn’t scare people away from taking their heartburn medication by any means,” Handley says. “But it suggests that those medications may be making them slightly more vulnerable to infection.”

The study was published online by Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Yersinia enterocolitica is a much less dangerous relative of Yersinia pestis, the bacterium that caused the Black Death in Europe and Asia during the Middle Ages. In humans, Yersinia enterocolitica infection usually causes only mild symptoms.

Researchers are using infection by the bacterium as a model to help tease apart the complex melee of biological prodding and pushing that ensues when a pathogen invades and is recognized by a host. The rapid exchange of measures and countermeasures hosts and invaders deploy against each other determines whether the invasion will succeed or be quashed. More detailed understanding of the back-and-forth of that conflict helps drug developers find better ways to assist the host in beating back the invasion.

Ironically, science has previously recognized Yersinia for its ability to shut down host immune responses including the production of other inflammatory chemicals. The new insight about histamine production comes from an assessment of how Yersinia infection affects the activity levels of approximately 12,500 mouse genes. Scientists assessed changes in gene activity levels in Peyer’s patches and mesenteric lymph nodes, tissues in the gut that identify and are first responders to ingested infectious agents.

“We’re interested in finding out whether this response is specific to Yersinia or whether it can be generalized to other infectious agents,” says senior author Virginia Miller, Ph.D., professor of molecular microbiology and of pediatrics. “We’d also like to know if it’s specific to the gut, or if similar responses occur in skin and lung infections.”

Researchers also plan additional follow-up evaluation of other genes whose activity was affected by the infection.

“We have quite a bit of raw information from this experiment that can be mined for further insights,” Handley says. “There are definitely other interesting changes to look into in more detail.”

Handley SA, Dube PH, Miller VL. Histamine signaling through the H2 receptor in the Peyer’s patch is important for controlling Yersinia enterocolitica infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, May 22, 2006.

Funding from the National Institutes of Health supported this research.

Washington University School of Medicine’s full-time and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked fourth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.