Alex A. Kane’s office is filled with neat rows of softball-sized skulls with various deformities. The skulls are models representing the kinds of problems he treats as one of the region’s premier pediatric plastic and reconstructive surgeons, and he is passionate about them.

Kane, M.D., describes a model of hemifacial microsomia, a birth defect in which one half of the lower face is underdeveloped. Then he reaches for an acrylic, magenta skull model of one of his patients with hemifacial microsomia whose jaw developed incorrectly after a prior surgery. The model was created by combining serial images of her skull using technologically advanced scans and then was sterilized for use in the operating room to guide the surgeons in the difficult repair, allowing the surgeon to visualize the anatomic problem on the model and thus keep the incisions to a minimum and reduce scarring.

Kane’s accomplishments in the field have lead to his recent appointment to a named professorship: the Dr. Joseph B. Kimbrough Chair for Pediatric Dentistry in the Washington University Department of Surgery, Division of Plastic Surgery for Use in the Cleft Palate/Craniofacial Deformities Institute for teaching and healing. It is a nod to his extraordinary reputation as a researcher in craniofacial imaging and as a skilled surgeon.

Kane’s specialty is the surgical repair of cleft lip and cleft palate, which affects one in about 600 births and leads to a variety of problems, including those related to facial appearance, unclear speech, poor hearing and inadequate dental health.

As section chief of the Division of Pediatric Plastic Surgery and director of the Cleft Palate and Craniofacial Institute at St. Louis Children’s Hospital, Kane coordinates treatment that is dedicated to ensuring that the patient will have both excellent function and appearance after surgery.

“If we don’t repair cleft palate, speech will be nearly impossible to understand,” he says. “Although these children have their palate repaired in infancy, up to a quarter of kids still have a residual speech problem requiring surgery by the time they are ready for kindergarten. We want to know why their palates don’t move appropriately, and we want a good four-dimensional way to look at how things move. That’s one thing we’d like to accomplish with imaging.”

An associate professor of plastic and reconstructive surgery, Kane received specialized training in cleft lip, palate and craniofacial surgery through a fellowship at Chang-Gung Memorial Hospital in Taipei, Taiwan, where surgeons repaired about 500 cleft lip and palates a year, while St. Louis Children’s Hospital repairs about 60 annually, he says. Cleft palate is twice as common in Asia as it is in the United States, but researchers aren’t sure why.

In Taiwan, Kane studied under Samuel Noordhoff, M.D., a world-renowned surgeon who spent four decades performing cleft lip and palate surgeries in Taiwan.

“Alex is an excellent surgeon with the ability to handle tissues delicately,” Noordhoff says. “He has a very sensitive touch for the patient, particularly for children. The patient comes first, and he’ll do everything possible for that patient to get the best possible care.”

Kane has also taken his expertise to Cambodia, the Philippines, Vietnam and India, where he traveled in December on a teaching and surgical mission.

The Cleft Palate and Craniofacial Institute takes the team approach, working with two other School of Medicine pediatric plastic surgeons, Gregory Borschel, M.D., and Albert Woo, M.D., both assistant professors of surgery, as well as physicians and staff from otolaryngology, neurosurgery, audiology, speech/language pathology, psychology, dentistry and orthodontics.

Kane shuns one stereotype of surgeons, who are often thought to be attracted to the field by hands-on, immediate feedback rather than long-term relationships with patients.

“I’ve lucked into a field in which I have the privilege of following kids and developing important connections with patients from the time they are infants to maturity,” Kane says. “The position allows me to have intimate relationships with families over time, doing work that is not only immediate but has a long-range impact.”

Susan Mackinnon, M.D., the Sydney M. Jr. and Robert H. Shoenberg Professor and chief of the Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, says Kane has the admiration of his patients and their parents.

“Alex is the penultimate surgeon-scientist,” Mackinnon says. “His patients benefit from his all-encompassing knowledge of the field of pediatric plastic surgery and his technical excellence. Heis the unique combination of a critical thinker, expert technical surgeon and a gentleman.

“Alex’s dedicated focus on the assessment and treatment of patients with cleft lip and palate and craniofacial malformations has altered the management of these devastating problems,” she says. “He has combined expert surgical skillswith critical research thinking, and working with an outstanding team that he has assembled over the last decade, he has positively changed his patients’ lives forever.”

Career change

While earning a bachelor’s degree from Dartmouth College in computer science, Kane worked during the summers on Wall Street and took a job there after graduation, but after several years, he grew disenchanted with the finance industry.

After spending a summer driving a cab in New York City, Kane became attracted to medicine but lacked the premedical undergraduate background. So, together, Kane and his then-girlfriend, now wife, Phyllis, decided to make career changes. Phyllis earned a master’s degree in public policy from Columbia University in New York and then completed a second master’s in social work at the George Warren Brown School of Social Work. Kane completed his premed courses in the evenings at WUSTL’s University College while working full time in municipal finance at an investment bank.

Kane returned to Dartmouth College for medical school with an eye on surgery. He began a general surgery residency program at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and the School of Medicine. About halfway through the program, he became attracted to craniofacial imaging and found his calling.

“I was really turned on by what was then novel and is now quite common — 3-D imaging of kids and taking radiology data and showing it in a new way,” he says. “Previously what was flat and two-dimensional became three-dimensional with many new possibilities.”

Research focus

After his fellowship in Taiwan, Kane spent a year at the National Institutes of Health studying the use of MRI to research soft palate function. But imaging techniques have changed tremendously in the past 10 years.

“We now have on our desktop computers software that nearly instantly allows us to see a 3-D image of a complete skull made from a CT scan, which, when I started, took us about a day of work to prepare,” Kane says.

|

Alex A. Kane |

|

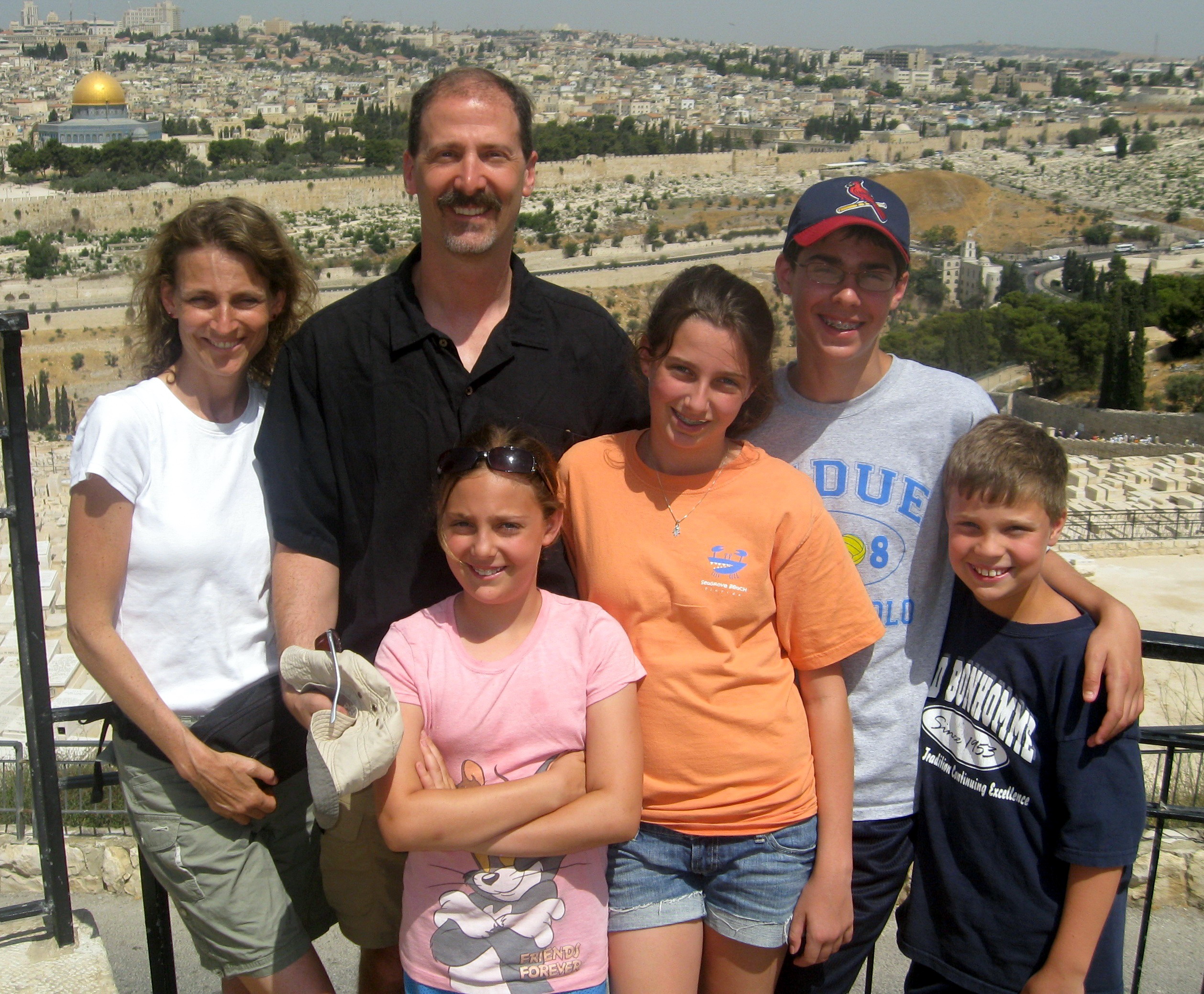

Hometown: Port Jefferson, N.Y. Family: Wife, Phyllis; children Zev, 15; Hava, 13; Mose, 11; and Geli, 9 Hobbies: Spending time with family, building furniture, running and swimming Other: Kane holds a U.S. patent on a device that allows lengthening of a bone by cutting it and slowly moving the pieces apart, which spurs new bone growth. The device is still in development. |

For a couple of years in the lab, Kane studied under Michael Vannier, M.D., and Jeffrey Marsh, M.D., former School of Medicine faculty who together published the first three-dimensional reconstruction of single CT slices of the human head.

“What we developed is this archive of scans of kids from the mid-1980s to the present that we still maintain,” he says. “We can take the old CT, MRI and surface-imaging data and reinterrogate it using new imaging techniques, which are ever-evolving.”

Kane also uses stereophotogrammetry, which uses multiple cameras to generate a 3-D image of a patient’s whole head without using radiation, so images can be taken repeatedly to evaluate patients over a long period. Kane and his students are using the technique to study facial asymmetry in patients at area pediatricians’ offices.

“Everyone has facial asymmetry, but it is a nontrivial task to figure out what is normal, in a rigorous way,” he says.

Results of this research could help surgeons have baseline data on normal faces to which they can compare patients with a variety of craniofacial problems.

Family man

Kane’s compassion for children also shows in his own family. He and Phyllis, who works in the Department of Psychiatry, have four children: Zev, Hava, Mose and Geli.

“They’re everything,” Kane says of his children.

In addition to spending time with his family, one of Kane’s hobbies is building furniture, a skill he learned as a child growing up on Long Island, N.Y.

His interest started with helping his father with carpentry tasks while rebuilding their home after a fire. As an undergraduate, Kane was employed in the student workshop.