Art may be subjective, but it is not entirely so. Aesthetic interest also can be understood in terms of a work’s power to engage cognitive and perceptual systems common to all human brains.

This is the central premise of neuroaesthetics, an emerging field that draws on neuroscience, psychology and philosophy to explore questions relating to beauty, artistic expression and art history.

It is also the premise behind Art and the Mind-Brain, now on view in the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum’s Teaching Gallery.

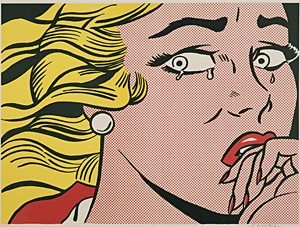

Curated by Mark Rollins, PhD, professor of philosophy in Arts & Sciences, the exhibition employs works from the museum’s permanent collection — by Joseph Albers, Romare Bearden, Georges Braque, Tom Friedman, Naum Gabo, Roy Lichtenstein, Joan Miró, Rembrandt van Rijn and others — to illustrate different, and sometimes competing, theories of pictorial representation.

At 5 p.m. Wednesday, March 7, Rollins will present a free public talk about Art and the Mind-Brain in the museum’s room 104.

“The oldest and most intuitive theory of pictorial representation holds that, unlike words, pictures represent objects by resembling them,” says Rollins, who organized the show in conjunction with a class of the same title. “According to this view, Roy Lichtenstein’s lithograph Crying Girl (1963) represents a crying girl only if we experience it perceptually much as we would a real girl crying (as we seem, in fact, to do).

“The problem is that, in many cases, the experience of the picture and its object are really very different,” Rollins says. “Our experience of Georges Braque’s Still Life with Glass (1930) is not very much like that of a glass on a table, yet the painting pictorially represents a glass on a table nonetheless.”

Thus, a second theory notes that viewers experience a picture’s content and design simultaneously — a twofold-ness possibly rooted in the division between the brain’s ventral and dorsal systems. A third theory holds that the brain recognizes what a picture represents by activating the same unconscious structures engaged by the object itself. For example, though characterized by very different artistic styles, Crying Girl and Joan Miró’s Portrait of Josep F. Ràfols (1917) both may activate some form of neural face recognition module.

Other neuroaesthetic theories speak to the mechanisms by which, for example, small involuntary eye movements may create an illusory sense of movement, or the ways in which mirror neurons influence the expression of emotion.

“This discussion of representation and expression suggests how cognitive science might provide new answers to other controversial questions,” Rollins says. “How, for example, do we interpret art, or ascribe larger meanings to it beyond simply recognizing the objects that may be represented or the emotions that may be expressed? What is the relevance of the artist’s intentions in that regard?

“By offering an opportunity to apply recent research in science to questions such as these, the works in Art and the Mind-Brain open the door to new conversation about the nature and power of art.”

Art and the Mind-Brain remains on view through April 16. The Kemper Art Museum is located near the intersection of Skinker and Forsyth boulevards. Regular hours are 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Mondays, Wednesdays and Thursdays; 11 a.m. to 8 p.m. Fridays; and 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays. The museum is closed Tuesdays.

For more information about the talk or the exhibition, call (314) 935-4523 or visit kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu.

In addition, the museum now is accepting proposals from faculty across the university for future Teaching Gallery exhibitions. For more information, and an archive of previous shows, visit the Teaching Gallery webpage; or contact Allison Taylor, manager of education programs, at (314) 935-7918 or Allison.taylor@wustl.edu.