Transplant surgeons and researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have received two grants totaling $10 million from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to study how immune cells contribute to organ rejection, with the aim of improving the viability of organs after transplant.

A $7.7 million program project grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases funds research to understand the immunological basis of lung transplant rejection.

And the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute awarded nearly $2.6 million to aid studies of the immune system’s role in heart transplant rejection.

“The ultimate goal is to improve the long-term outlook for lung and heart transplant patients,” said Daniel Kreisel, MD, PhD, the surgical director of lung transplantation at the School of Medicine and Barnes-Jewish Hospital, and a principal investigator of both NIH grants. “It is our hope that through our research, we will gain critical new insight into the immunological underpinnings of transplant tolerance and rejection.

“Understanding how immune cells respond to transplanted organs sets the stage for developing novel therapeutic strategies to improve outcomes for transplant patients,” said Kreisel, who is the G. Alexander Patterson, MD/Mid-America Transplant Endowed Distinguished Chair in Lung Transplantation.

For lung transplant patients, the risk of organ failure and death is particularly high. Five years after lung transplantation, about half of the lungs are still functioning, according to the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. This compares with five-year organ survival rates of about 70% for heart, liver and kidney transplants.

“Uncovering the basis for the poor survival of lung transplant recipients should also give us new insight into the causes of other inflammatory diseases that affect the lung,” said Andrew Gelman, professor of surgery, and of immunology and pathology at Washington University and the Jacqueline G. and William E. Maritz Endowed Chair in Immunology and Oncology.

The funding will support three projects — led by Kreisel, Gelman and Alexander S. Krupnick, MD, professor of surgery and director of the lung transplant program at the University of Maryland — that examine different immunological aspects of lung transplant tolerance. This refers to the ability of the immune system to recognize a transplanted lung as the body’s own.

Often, lung transplant remains the only option for patients with end-stage lung disease, a condition that can be brought on by emphysema, pulmonary fibrosis, cystic fibrosis and other lung disorders. Unlike other organs, lungs constantly are exposed to whatever is in the environment, including bacteria, viruses and air pollution. Such fragility contributes to the increased risk of chronic rejection and organ failure.

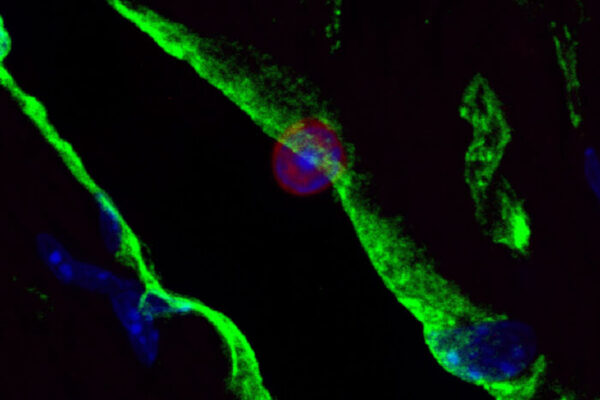

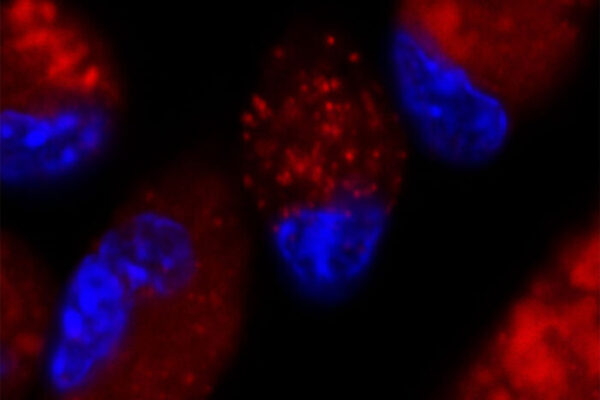

Also playing a key role in the research is Wenjun Li, MD, associate professor of surgery and director of microsurgery in the Thoracic Immunobiology Laboratory. He is highly regarded among transplant scientists for developing microsurgical and imaging methods that have advanced the understanding of lung and heart transplantation.

For heart transplant patients, receiving a new heart is one of the most viable options for end-stage cardiovascular disease. About 3,550 people received a heart transplant from a deceased donor in 2019, according to the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network.

However, heart transplant success can be threatened when the donor heart doesn’t work properly. This complication — called primary graft failure – typically occurs in the early days following surgery and can prevent a newly transplanted heart from supplying enough blood to the body’s vital organs.

Current treatments have focused on targeting immune cells in the recipient’s heart. “These have many side effects and are only modestly effective,” said Kory J. Lavine, MD, PhD, a Washington University associate professor of medicine in the Cardiovascular Division and also one of the principal investigators. “Our research will focus on alternative approaches based on targeting immune pathways and cell populations in the donor heart. We hope that insight gained from the research will result in new therapies that will increase donor heart availability and improve survival after heart transplantation.”