“Don’t do it,” her friends and family said. “Donating a kidney is serious. … Surgery can be dangerous. … You’re only 22.”

“What if you need your kidney one day?” her mom asked.

“What about medical school?” her dad asked. “Your future?”

“You should be having fun,” her friends said. “Have you thought this through?”

The truth is, Morgan Pfeiffer hadn’t given extensive thought to donating her kidney.

She had seen a Facebook post from a former babysitter whose grandson needed a kidney. Without one, the boy’s childhood would entail dialysis and hospital stays — or he could die.

On a whim, Pfeiffer decided to give the boy she’d never met one of hers.

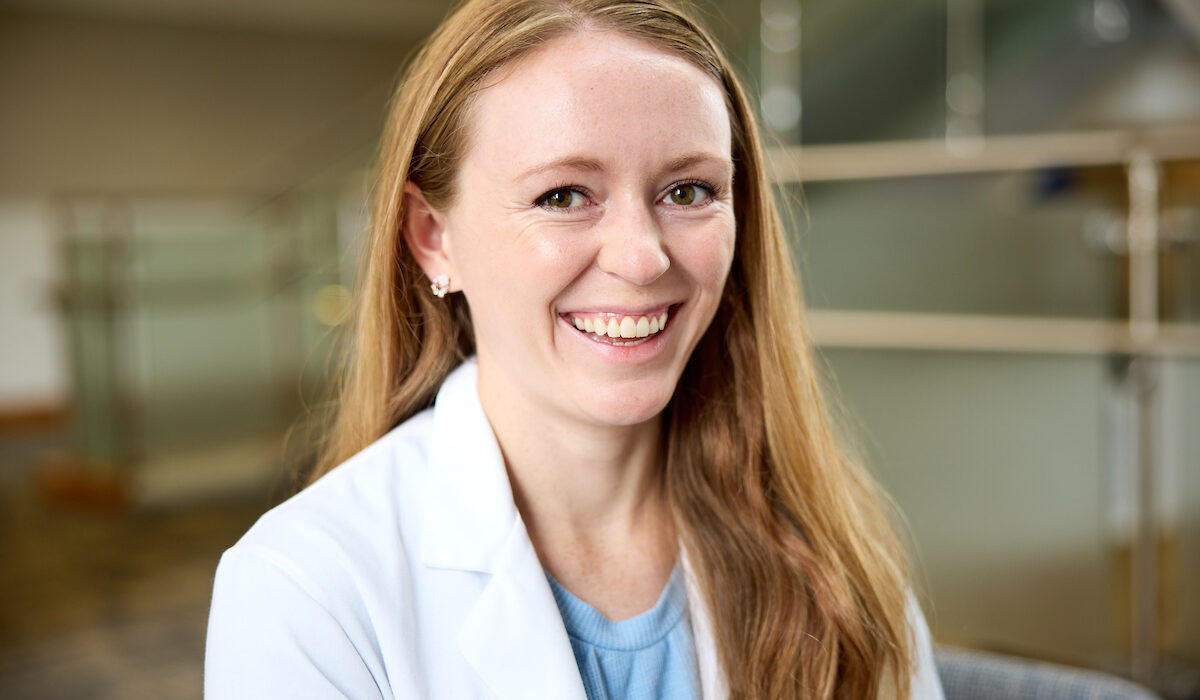

She had no idea that doing so would serve as a guidepost during medical school, inspiring her decision to become a pediatrician while providing unique perspectives on patient care. That entire experience will culminate May 20, when Pfeiffer receives a medical degree from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. In July, she will begin residency training in pediatrics at St. Louis Children’s Hospital.

“Donating a kidney has influenced my path in medicine,” Pfeiffer said. “It’s taught me the importance of compassion and empathy. I have learned many lessons — practical things, emotional things — that I can take with me as a doctor.”

Lesson No. 1: It’s OK to prioritize emotions when making decisions (even when you’re a data-driven, methodical believer in science).

Pfeiffer became teary-eyed in April 2017 when she saw a Facebook post seeking a living kidney donor for 17-month-old Wilton “Will” Schweitzer — and also for his father. The toddler’s kidneys were failing because of a congenital disorder; his father’s kidney failure stemmed from inflammatory bowel disease.

They were the grandson and son of Vickie Schweitzer, who ran an at-home, summer day care attended years before by Pfeiffer and her younger brother. Schweitzer lived on a sprawling farm near Pfeiffer’s home in Friend, Neb., an old railroad town an hour southwest of Lincoln, Neb. Bricks pave the main streets and, according to Ripley’s Believe It or Not, it has one of the world’s smallest police stations.

At the farm, Pfeiffer and other kids rode tractors with Schweitzer’s husband, Larry; raced trikes and bikes around the “endless” circle driveway; and ate homemade cheese pizzas for lunch.

“It was a wonderful, unstructured environment where we all got to play and be little kids together,” Pfeiffer recalled. “Vickie and Larry went above and beyond for us.”

Her bond with the Schweitzers compelled Pfeiffer to click on the Facebook link and fill out a form offering herself as a prospective kidney donor.

“I feel very connected to the family, and I want to show my support,” she reasoned, hitting the submit button.

Ingrained in small-town life is a feeling of responsibility for one another and a desire to help neighbors, even if it means great personal sacrifice, Pfeiffer said.

Initially, she didn’t dwell on the scariness of kidney donation. “There’s no way I’m going to be a match,” Pfeiffer told herself.

The next morning, she got a call. “We’re interested in you being a donor for either the boy or the dad,” said a nurse with a transplant team in Nebraska. “Can you come in for blood work and screening?”

Pfeiffer noted eagerness in the nurse’s voice. “I guess they don’t get a lot of 22-year-olds who are like, ‘Yeah, I have perfect kidneys, and I’m just going to part with one of them,’” Pfeiffer said, looking back.

Her excellent health, O-positive blood type and smallish kidneys made her an ideal donor match for Will.

Four months later, on Aug. 1, 2017, Pfeiffer underwent surgery. Her left kidney now lives — thrives — in Will’s body.

Lesson No. 2: Medicine straddles life and death. It’s OK to be afraid, but also do your research so you can make informed decisions (true whether you’re the physician or the patient).

After Pfeiffer learned she was a donor match, she wrestled with doubt and fear. What if having one kidney could jeopardize her health? What if Will’s body rejected her kidney? What if she had to give up running or other activities she enjoyed? What if her donor status prevented her from obtaining health, life or disability insurance?

What if, what if …

Her parents offered support but admittedly, understandably even, had major concerns.

“Morgan has a big heart,” said her mother, Sally Pfeiffer. “We wanted to make sure she had thought it through. We worried about her health and future.”

“Before you agree to giving a kidney, do your homework,” advised her father, Jim Pfeiffer, the only local high school science teacher. He had his daughter in class all four years.

Once donating a kidney became a reality rather than a gesture of support, Pfeiffer began researching in earnest. Based on interviews with physicians and patient donors and recipients, as well as a review of scientific studies, she learned that:

- Kidneys filter waste from the body. Improperly functioning kidneys in children can cause growth delays, learning disabilities and neurological problems.

- Adult kidneys — roughly the size of a fist — can be successfully transplanted into small children.

- The only long-term survival options for kidney failure are dialysis or transplant.

- A child’s body is less likely to reject kidneys from living donors than deceased donors.

- Children without living donors can wait up to five years for kidneys from people who have died.

- Healthy kidney donors experience no changes in life expectancy and no increased risk of renal failure; in fact, most people with a single healthy kidney have few or no problems.

Such facts eased Pfeiffer’s mind. She concluded the overall risks to her health were small compared with the significant challenges confronting Will.

“Kids with kidney failure don’t get to have normal childhoods,” she said. “They’re stuck in hospitals for days or months. Many don’t get to go to school or play with friends.”

According to Will’s mom, Talicia Schweitzer, Will is now a happy, healthy 6-year-old boy who is finishing kindergarten. “He’s learning to read and can count to 100,” she said. “He likes dirt bikes, T-ball and Pixar movies such as ‘Toy Story’ and Cars.’ Lightning McQueen is his favorite character. He likes eating chips and going to the zoo with his older sister and brother.”

Lesson No. 3: Statistics tell part of the story, but true understanding is impossible without empathy (especially when you find a person’s viewpoint inexplicable).

Pfeiffer may have been younger than the woman who donated her kidney to Will’s dad. But there they were, recovering post-op in nearby hospital rooms in Nebraska. “She was doing amazing, and I wasn’t,” Pfeiffer recalled.

Pfeiffer didn’t receive nerve-numbing medication during the surgery. Her care team thought she had, so they didn’t immediately give Pfeiffer pain meds post-op.

“My pain was horrific,” said Pfeiffer, who has since recovered fully from the transplant.

“However, the experience made me realize that while double-checking prescriptions may seem like a small or annoying task because health-care providers do it a zillion times a day, it means everything to patients and can shape their perspectives about medical care,” she said. “I promised to remember this once I became a physician.”

In medical school, Pfeiffer honed her ability to empathize. She was drawn to Washington University, in part, because of its emphasis on compassionate medicine and addressing health inequities. Classes and clinicals inspired her to contemplate health care in rural America.

“I loved going to the doctor, especially as a kid,” Pfeiffer said. “I got stickers and suckers, and my doctor was fun, and I thought everything was fascinating. I hadn’t considered that other people felt differently about doctors.”

Upon further reflection, she remembered people who avoided doctors because of distrust, distance, costs, and cultural or religious reasons. She started noticing barriers to health care such as poverty, limited preventive educational programs, local doctor shortages and a lack of access to clinics and hospitals. The latter has become particularly worrisome in rural areas, which have higher than average numbers of elderly residents, who often need specialty care that is miles away in bigger cities.

“Medical school helped me realize that we, as physicians, need to do a better job at forming relationships with our patients and taking the time to explain their health in a genuine, caring way,” Pfeiffer said. “It’s up to us to motivate them to take care of their health, stay connected to resources and navigate barriers.”

St. Louis Children’s Hospital serves urban and suburban patients, as well as kids from rural Missouri, Illinois and surrounding states. “My priority is to be respectful and compassionate so kids develop positive associations with doctors and feel confident seeking medical care when they grow up,” Pfeiffer said.

“Morgan displays spectacular communication skills,” said Colleen M. Wallace, MD, an associate professor of pediatrics and one of Pfeiffer’s faculty mentors. “She engages with and advocates for patients and families and meets them where they are. She displays an obvious love of children and families, always going out of her way to build rapport and communicate with empathy, respect and kindness.”

Lesson No. 4: You can’t force yourself to love a kidney or a liver (but you love kids, so go with that).

After so much focus on the kidney, Pfeiffer wondered if she might like to specialize in transplant medicine. But then she did a clinical rotation in pediatric transplant.

“Do I like a liver enough to devote my career to it?” she asked herself. “Do I love the kidney?”

Meh.

But the kids?

Looove.

“Kids are just fun,” Pfeiffer said. “They’re so strange and interesting, with clearly defined likes and dislikes. And they’re brutally honest, which is refreshing and helpful as a physician. They see the world with spirited optimism and goodness. I like the team aspect of it. Parents, kids … we’re all working toward the same goal. It’s very meaningful. Kids also have the best perspectives: They prioritize play.”

Pfeiffer colored more during her pediatrics rotation than she had in the past decade.

One girl, who was about 8 years old, had to stay in the hospital for six weeks for intensive antibiotic treatments. “I’d visit her for an hour or so before going home,” Pfeiffer said. “I loved how I’d walk into her room, and she’d say with authority, ‘I have plans for us today. We’re doing crafts.’”

Which meant making slime.

Other times, they created elaborate, theatrical, silly stories with dolls. “She missed her family, who couldn’t be with her,” Pfeiffer said. “We would make up stories about what her dad and her brother were doing at home. Like, ‘I bet your dad is flying to the moon today.’ And she’d continue the story about her dad on the moon.”

Every now and then, when Pfeiffer goes back to Nebraska, she visits Will. “He knows me as Morgan, the goofy girl who brings him presents,” she said. “He’s always up for playing. He draws me pictures.

“He doesn’t know it, but he helped inspire me to pursue pediatrics.”

Nor does he know that her kidney is now his. And it’s why he can ride his dirt bike, play T-ball and eat chips at the zoo with his siblings. It’s why he can live a normal childhood.