In 2020, Washington University in St. Louis joined St. Louis Public Schools (SLPS) in a bold new experiment to turn around two of the district’s lowest performing elementary schools, Ashland Elementary in North St. Louis and Meramec Elementary in South St. Louis.

Only it wasn’t an experiment at all.

“It’s no secret what works,” says Victoria May, executive director of the university’s Institute for School Partnership (ISP). “The challenge is how do you make it work. How do you create a culture of excellence that makes everyone — teachers and students — want to come to school every day because they care so much.”

The answers: empower teachers to lead alongside principals, provide staff the training and time needed to put evidence-based practices into action, raise student voices and engage parents. That may sound like squishy “edu-speak,” but the results are undeniable. Three years ago, less than 10% of the students at Ashland Elementary and Meramec Elementary — the two schools that make up SLPS’ Community Partnership Network — met or exceeded basic standards in math and science. The most recent MAP scores show that 27% of students now meet math standards and 47% meet science standards. That’s a 2.5-fold increase in math and 5-fold increase in science at a time when many schools suffered learning loss due to the pandemic.

“I’m not saying all is well,” Jay Hartman, CPN executive director, recently told teachers during a planning session. “This is really hard work. A lot of it is messy. But the growth that you are showing as a team across all grade levels is exciting. You should feel encouraged, a sense of accomplishment, as we continue to tell our story.”

Modeled after the Springfield Empowerment Zone Partnership in Springfield, Massachusetts, SLPS’ two CPN schools are accountable to the district but are encouraged to try new approaches to teaching, staffing and resource allocation. Of course, flexibility, in and of itself, won’t help third graders master multiplication. But give teachers — the educators closest to students — the power and the responsibility to create better lessons, improve classroom practices and coach each other, and good things will happen.

“Teachers need to see themselves as intellectual experts before cultivating the same thing in their students. … They need time and the opportunity to dream and design and build and retool. And they need the resources to put their ideas into action.”

Nikki Doughty, ISP associate director

To help develop these teacher leaders, the CPN enlisted the ISP, a recognized innovator in STEM education and teacher development. The ISP also administers the Transformational Leadership Initiative (TLI), which is helping schools across the region transition from a top-down leadership structure to a distributed leadership model that fosters creativity and improves school culture. For the past three years, through TLI, ISP provided CPN teachers summer professional development, weekly one-on-one coaching and teaching assessments, and helped teachers develop lessons that favor conceptual understanding instead of rote memorization.

“Teachers need to see themselves as intellectual experts before cultivating the same thing in their students,” says Nikki Doughty, ISP associate director. “Providing teachers with a curriculum and a script won’t lead to a culture of excellence. They need time and the opportunity to dream and design and build and retool. And they need the resources to put their ideas into action.”

At Ashland that means smaller class sizes, a school “Wellness Hub” supported by the Little Bit Foundation and St. Louis Area Food Bank, and training opportunities with some of the nation’s most respected teaching experts. The school also introduced place-based learning as an exciting and effective way to connect lessons to the local environment.

‘You have a great idea. Now do it.’

Place-based learning is hardly new. If you’ve ever been on a field trip to the local history museum or nearby farm, you’ve experienced place-based learning. But to Ashland Principal Paula Boddie, placed-based learning is more than an effective pedagogy; it’s a moral obligation. Many of her students don’t know that Fairgrounds Park, right across the street, once had barracks for Black soldiers, or that Black children, like Boddie’s own grandmother, were not allowed to study at Ashland.

“Our children need to know the value of this community,” Boddie says. “It’s not just about learning the history. It’s about connecting this place to science, to mathematics. I want to give our children the knowledge they need to advocate for the place that is their own. Because if you have strong roots, nothing can tear you down.”

Boddie, a graduate of SLPS, served as a reading specialist and kindergarten teacher before she was asked to lead Ashland Elementary six years ago. She sees herself as an old-school educator who has strong ideas about how a teacher should dress, speak and line up their classes for recess. But her vision of what it means to be a principal has evolved.

“I am a collaborator,” Boddie says. “I say, ‘I want to give you space to be the artists that you are. I don’t want to dictate what your lesson has to contain or what it has to look like.’ I need my teachers to be better in order for my children to be better.”

So when CPN teacher-leaders from kindergarten, first and second grades recommended adding a quiet period after lunch to reduce disruptive behaviors, Boddie was all for it.

“My attitude is, ‘You have a great idea. Now do it,’” Boddie says.

‘Don’t be afraid to show your genius’

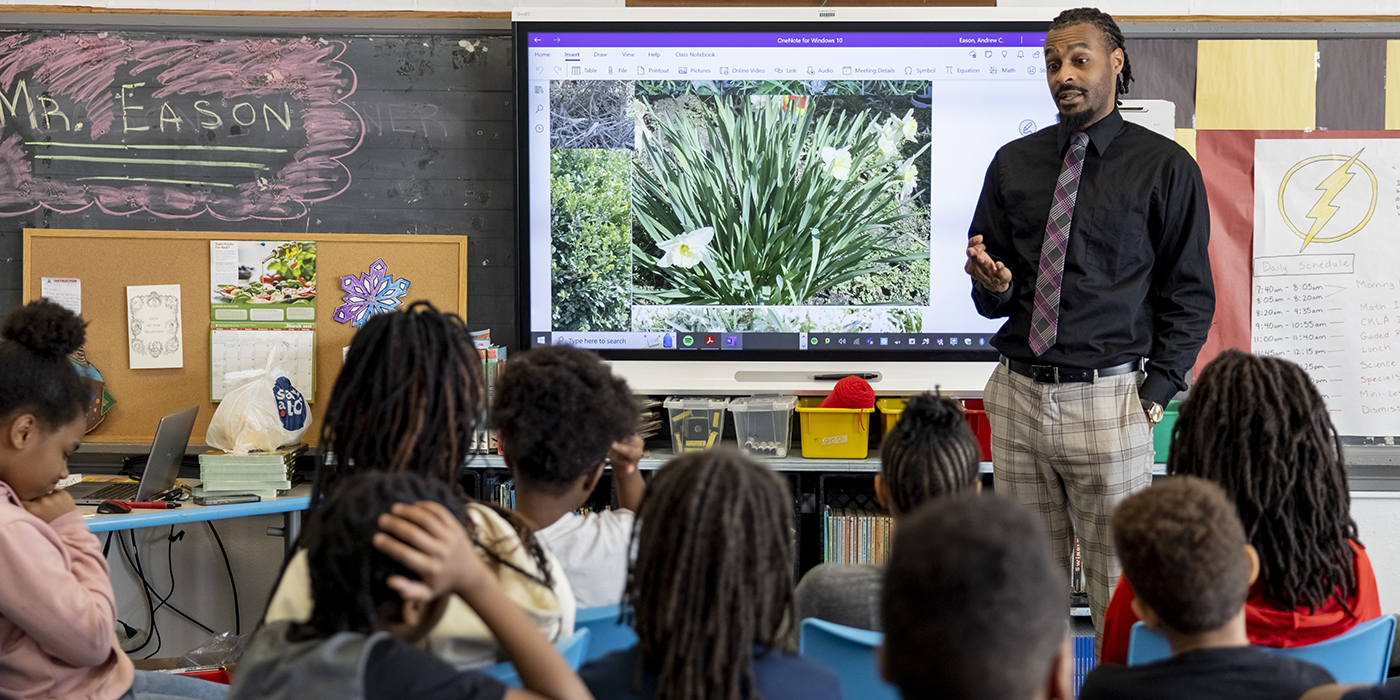

Ashland fifth-grade teacher Andrew Eason is full of good ideas. This afternoon, the class is studying pollination, pretty standard stuff for fifth-grade science. But Eason’s lesson did not start nor end with plants. Months earlier, his students initiated a discussion about the lack of nearby grocery stores with fruits and vegetables. And more recently, Eason led a discussion about the rise and decline of Black farming in America. What if, the class wondered, they started their own community garden. So the class researched grocery stores, visited a community garden and even traveled to the Missouri State Capitol to understand how laws are made. Later, Eason extended the lesson, drawing the connection between trees, pollution and asthma.

“I don’t teach subjects in isolation,” Eason says. “Adults don’t say, ‘I think I’m going to do some math today.’”

After drawing the different parts of plants, the class goes outside to photograph the stems, roots and leaves of the school’s trees and bushes. Back in the classroom, Eason asks the students to roll their chairs to the smartboard where he projects their photographs.

“Are bees the only pollinators?” he asks.

The class is silent, but then Michael shoots up his hand.

“I know a way to pollinate plants! The wind!”

“That’s right! What does the wind do?” Eason asks.

The conversation takes off with students debating whether bugs can pollinate plants.

“Don’t be afraid to show your genius,” Eason tells the students. “You have it in there. You need to have the courage to say it.”

Eason has applied the distributed leadership model in his own classroom. Students set the agenda for morning meetings and lead classroom discussions. They also are expected to actively wrestle with lessons, not idly sit at their desks.

“When you are not focused on checking boxes and one little lesson, you can let the lesson flow so kids really take ownership of their own learning.”

Andrew Eason

Take, for instance, math instruction. In many underperforming schools, teachers will drill students on math formulas in preparation for high-stakes standardized tests. But the most successful math teachers don’t “teach the test,” they challenge their students to discover multiple strategies to solve a single problem. The result is deeper understanding, more confidence and, yes, higher test scores.

“This experience has opened my eyes to different ways of doing things,” says Eason, who attended conferences this year on experiential learning and math education, both funded by the ISP. “Growing up, I had this idea of what a teacher should look like. You have a stern face and don’t make jokes. But I’ve learned that I can be a little more free in my instruction. When you are not focused on checking boxes and one little lesson, you can let the lesson flow so kids really take ownership of their own learning.”

It’s easy to watch Eason and think that he should lead his own school. But Eason does not want to be a principal. And wouldn’t taking Eason out of the classroom undermine the whole point of the distributed leadership model?

“I am a teacher,” Eason says. “Adults, kids, whoever. If you’re ready to learn, I’m ready to teach, because I love it.”