Perhaps no name is as recognizable — or has been as important to the success of Washington University — as the name Danforth.

From William H. Danforth, who established the Danforth Foundation in 1927; to his son, Donald Danforth, who served as chair of the Danforth Foundation from 1955-1965; to a grandson, also William H., who served as chancellor of the University for 24 years (1971-1995); to another son, John C. Danforth, who chaired the foundation upon his retirement after 18 years in the U.S. Senate in 1997, the Danforth name has made an indelible imprint on the University.

And Chancellor Mark S. Wrighton and the Board of Trustees have taken steps to ensure the Danforth imprint remains as long as there is a Washington University.

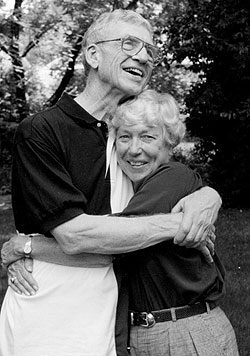

On Sept. 17, the Hilltop Campus will be named the Danforth Campus in a ceremony from 3:30-5 p.m. in Graham Chapel. The naming of the campus is to honor the legacy of Chancellor Emeritus William H. Danforth and his late wife, Elizabeth (Ibby) Gray Danforth; the Danforth family and its contributions; and the support of the Danforth Foundation. The ceremony is open to the public, but registration is required at danforthcampus.wustl.edu.

“Naming the main campus the Danforth Campus is a wonderful double play,” says Frank H.T. Rhodes, president emeritus of Cornell University. “It’s a great tribute to the Danforth family, especially to Bill and Ibby who poured their lives into that campus, and also to Jack and Donald and their family foundation, which was so generous to the University.

“It reminds me of architect Christopher Wren’s marker at St. Paul’s (Cathedral) in London. The inscription there says ‘Lector, si monumentum requiris, circumspice’ — ‘Reader, if you seek a memorial, look around you.’ Now when people look around the Washington University campus they can say the same things about Bill and Ibby Danforth and his family.”

Building a community

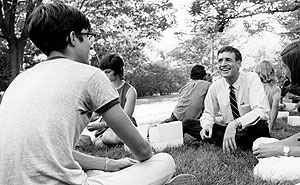

It didn’t take long for William H. Danforth to make his mark on the University. In fact, he set out to help incoming freshmen each year understand their new community and how to “catch the excitement of learning and growth.”

In his address to the 1974 freshman class, Danforth spoke of a friendly campus and of active, contributing scholars who care about teaching. At the same time, he reminded his young audience of its responsibility: “While we believe the environment at Washington University is conducive to learning, we know that neither the environment nor the faculty can learn for you any more than the people in the food service can eat for you. You must do it for yourself. Learning is never easy. … The faculty expect much of themselves and will expect much of you.”

As freshmen from suburbia and the inner city, from all over America and from abroad, from every sort of religious background, listened to this preface to their next four years, they received a principle for their lives.

Observing that the students would soon be taking part in common intellectual, cultural, social and athletic activities, Danforth said, “I hope that as you share experiences you will also share yourselves freely, so that this class might contribute to building an open, friendly, supportive community of people who are different from one another but who listen to each other, respect each other, understand each other and care for each other.”

Danforth’s address reflected his hopes for all undergraduates — who year after year returned his regard: dropping by his office to talk; planning events to celebrate the reassuring campus figure they called Uncle Bill and later Chan Dan; thronging to his annual Bedtime Stories event on the South 40, where his instructive tales ranged from James Thurber to family chestnuts.

Strong ethical principles, the quest for improvement and concern for others — the guiding principles of Bill, Ibby and the larger Danforth family — define the University’s 13th chancellor, whose description in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat as a “Lincolnesque figure of granite laced with steel and wrapped in velvet” spoke as much of his character as of his presence.

“Bill and Ibby Danforth set a tone and operating style for Washington University unlike that at any other major university,” says Edward N. Wilson, Ph.D., professor of mathematics in Arts & Sciences and grand marshal of Commencement. “Others may talk about wanting to establish an extended family atmosphere on their campuses, but I strongly suspect none other than the Danforths have succeeded in doing so.

“They cared about everyone connected with the University — students, faculty, staff, alums, friends — and all of these groups had no doubts about their caring concern.”

Danforth’s faith in the simple virtues and in optimism based on hard work and a sense of the possible were implicit in his actions. The culture of inclusion, integrity, academic freedom, collaboration and accomplishment this modest man painstakingly tended had much to do with what he and the thousands of individuals he inspired were able to accomplish. As Wrighton said when he announced the campus naming: “He personifies Washington University.”

“The Danforth era was one of enormous growth in stature for Washington University,” Wrighton said. “Naming our campus the Danforth Campus is a reminder of the important values and aspirations represented by the Danforth family and honors them for their leadership and contributions to the development of a great university.”

Settling the unrest

When Danforth and Ibby became chancellor and first lady July 1, 1971, the campus was still experiencing student unrest over the Vietnam War, culminating in the burning of the Air Force ROTC building on May 5, 1970.

Two additional problems awaited. One was that the University’s income had not kept up with spending. The other was the disaffection of the St. Louis community: The divisive war had shaken public confidence in universities nationwide, and many St. Louisans felt estranged from the University.

“Dr. Danforth has a remarkable rapport with the leadership of the St. Louis community,” says Shanti K. Khinduka, Ph.D., the George Warren Brown Distinguished University Professor and dean of the George Warren Brown School of Social Work from 1974-2004. “He assumed the chancellorship of the University at a time when many influential members of the St. Louis community had begun to question the direction of the University.

“He won their support, loyalty, affection and respect, and gave them a new sense of pride in the institution, without in any way compromising the integrity and autonomy of the University. He has an uncanny and impeccable sense of the institution, and in every meeting or conversation, it is this sense of Washington University as an entity larger than the sum of its parts that comes through clearly and convincingly.”

The new chancellor — who a few years earlier had transformed the medical center to a place where people talked about common goals — seized the earliest opportunity to reach out to the community. In his first official address on Founders Day 1972, he conveyed a native son’s empathy for his city and called for reconciliation between St. Louis and the university he was leading. The tension arose from a “failure to know one another well,” said Danforth, who went on to speak of the University as one of the community’s contributions to mankind. At that time, he began to build the strong relationship between the University and the St. Louis community that endures to this day.

“As chancellor and first lady, Bill and Ibby Danforth set the perfect tone for Washington University,” says John Berg, associate vice chancellor for undergraduate admissions and former assistant to Chancellor Danforth. “When you saw them on campus and when you heard them speak, you realized the profound impact they have had on the University.

“They helped create a wonderful environment — one filled with kindness, acceptance of others — for the entire campus community to come together in pursuit of learning. They made everyone want to be a part of Washington University.”

Danforth was equally quick to address the University’s financial problems. While he served as medical vice chancellor (1965-1971), he proactively forged a relationship, for example, with the medical school at Saint Louis University and secured a federal planning grant that helped obtain federal funds for combating heart disease, cancer and stroke.

He approached his chancellorship in the same way. By 1973, a new fund drive began, with the news of a $60 million endowment challenge grant from the Danforth Foundation. When the matching goal was achieved, the chancellor noted that the money would ensure stability for long-range planning.

Other milestones were the establishment of the Spencer T. Olin Fellowship Program for Women in graduate and professional studies and the McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences, placing the University among a handful of schools featuring such centers.

In the same period, as research and major discoveries were bringing worldwide recognition to the medical center, Danforth supported P. Roy Vagelos, M.D., (then professor and head of biochemistry) in the development of a joint Division of Biology and Biomedical Sciences. Known as DBBS, the now much-copied concept is an educational consortium of faculty affiliated with 29 basic science and clinical departments on the Danforth and Medical campuses.

Danforth continued the efforts, begun while he was vice chancellor for medical affairs, of the Washington University Medical Center Redevelopment Corp., which completed a nationally acclaimed renewal of the decaying urban neighborhoods north of the medical center, now called the Central West End.

Danforth had said at the outset that “in the future, the United States will probably afford about 30 to 35 first-rate universities (and) Washington University certainly will be and must be one of these.” But to realize that goal, another major fund drive was essential.

Looking forward

In 1978, Danforth announced a plan emblematic of his administrative approach: the Commission on the Future of Washington University, comprising 10 task forces chaired by trustees with impeccable credentials, each assigned to a school or major service area.

“Having wonderful, smart people was very, very important,” Danforth says today of the talented leaders he brought to the table throughout his chancellorship. “I talked with them about their ideas and always felt I was doing the right thing if I was backing the convictions of people I knew were wise.”

For 28 months the task forces studied the University, talking in depth with its constituencies, and in 1981 compiled a report with nearly 200 hard-hitting recommendations aimed at strengthening the University.

The Commission’s work not only provided a map for the 1983-87 ALLIANCE FOR WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY campaign — which raised $630.5 million and was then the most successful university fundraising effort in national history — but also presaged Danforth’s establishment five years later of the 10 National Councils, one for each school, the Libraries and Student Affairs, to extend the analysis, insights and dialogue. Each chaired by a member of the Board of Trustees, the councils are made up of alumni, parents and leading national and local academic, corporate and civic leaders who bring expertise and objectivity to institutional planning.

Using the comprehensive strategic planning approach that had preceded the ALLIANCE campaign — and enjoying “the comradeship of working side-by-side with others who share visions which we hold dear” — Danforth launched three initiatives aimed at positioning the University for the future: Project 21, the Task Force on Undergraduate Education and the University Management Team.

Heralding the Campaign for Washington University that Chancellor Wrighton would announce publicly in 1998, Project 21 was an incubator for new ideas, long-range planning and action that provided a detailed blueprint for how the individual units and the University as a whole could realize their potential.

The exercise brought together constituencies essential for improvement — deans and faculty of the schools, and the University Libraries and Student Affairs, who worked with their National Councils. It also nurtured a sense of belonging and excitement about the University’s promise and consolidated a strong base for future collaborations.

A quietly powerful presence behind the progress, Danforth helped to lay what he called “the cement of mutual confidence” and created stability in every area. His rare combination of enormous vision and sincere concern for the individual and his manifest integrity fostered the cooperation essential to advancement.

He was the linchpin for the energetic alumni programs, treasuring his contact with former students from every decade — the “people armed with intelligence, energy and understanding” who had graduated “ready to make their contribution to the advancement of society.”

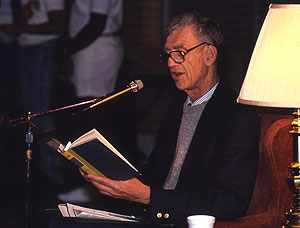

Danforth also revered the faculty and regarded these intellectual leaders as essential to the University’s contribution to progress. In 2000, the American Association of University Professors presented him with the Alexander Meiklejohn Award in recognition of his “daily, consistent defense of academic freedom over an entire career.”

During his tenure, 11 Nobel Prizes and two Pulitzer Prizes went to people associated with the University, along with innumerable other prestigious honors. Two faculty members served as poets laureate.

“As Chancellor, Bill Danforth quietly, generously and steadfastly supported my work, the activities of The International Writers’ Center, and the entire Washington University community of writers,” says William H. Gass, Ph.D., the David May Distinguished University Professor Emeritus in the Humanities in Arts & Sciences. “He never failed us, and he made much of the University’s prestigious position in the literary scene possible. We are all deeply indebted to him.

“Chancellor Danforth was a profoundly principled administrator. His was an ethically responsible rule. Yes, he looked a bit Lincoln-like, but he was Lincoln-like.”

Characteristically, Danforth chose a time to retire that was in the best interests of the University. Project 21 was under way, and he believed a new chancellor should be in place to oversee the plan’s final form. The day after Danforth “graduated,” as he put it, he went right back to work, as chairman of the Board of Trustees.

That same year, in 1995, Elizabeth Gray Danforth received an honorary doctor of humanities from Washington University.

At the 1999 Commencement, Bill Danforth both delivered the address and received an honorary doctorate; that same year, he became chancellor emeritus, vice chairman of the Board and a Life Trustee of the University.