Talking to Martin Cripps is bound to make anyone just slightly jealous. For one thing, the man is unusually giddy. Whether he’s talking about his London upbringing, his family or his work, the youthful economics professor finds a way see the lighter side of life and laughs readily at it.

Cripps, Ph.D., was recently installed as the John K. Wallace and Ellen A. Wallace Distinguished Professor of Managerial Economics at the Olin School of Business, which tells you that his jolliness doesn’t get in the way of producing work worthy of such accolades.

It’s easy to understand where the happiness comes from when you consider how he sees the world. When it comes to his job, for example, Cripps finds it amazing that someone pays him to sit around and create mathematical theories about topics such as what makes or breaks a reputation or how to optimize efficiencies in auctions. His work is abstract to the layperson, yet the way Cripps presents it is at once concrete and playful.

“Take gazelles,” Cripps says to explain his research on why reputation matters. “There’s a certain type — Thomson’s gazelle — that engages in something called ‘stotting.'”

That’s when a gazelle starts jumping up and down when the herd is confronted with a predator. Not all gazelles in the herd start stotting when they’re aware of the predator; it’s mostly the young and strong.

“Why would they do that? What are they signaling by hopping up and down?” Cripps asks. “Are they saying, ‘Hey, eat me. I’m tired and can’t run away?’ Or are they trying to warn the other gazelles? Or perhaps they’re frightened?”

As it turns out, Cripps says, jumping is a clever way for the gazelle to signal to the predator, “Hey, I’m a really fit gazelle. Don’t even try to catch me.”

That message establishes the stotting gazelle’s reputation with the predator.

The gazelle has learned that hopping around might tire him out in the short term but over the long hall, stotting every time the predator appears builds the reputation that he is not a gazelle to be trifled with.

Since Cripps is an economist and not a biologist, he didn’t come up with this theory about stotting. But he does create theories that help explain the larger impact signals have on one’s reputation — not just for gazelles, but for businesses in general or people trying to sell stuff on eBay or the even for the federal government.

“And they pay me to do this!” he says — a recurring theme for Cripps.

Luckily, his open appreciation for his privileged position makes it impossible to bear him any malice. Cripps doesn’t come from a family of academics. Born in the East End of London, he’s the first one in his family to have graduated from a university.

“All my family are plumbers or whatnot,” Cripps says. “My grandfather was a glazier and my dad grew up in the East End. He was the only boy in the family to go to grammar school. He actually got a spot in Oxford but he wasn’t allowed to take it because he needed to get out there and earn money. So, he was a well-educated probation officer.”

Between his well-read father and his schoolteacher mother, Cripps was instilled with the love of learning. So when it came time to graduate from college, he passed up an opportunity to work as a foreign exchange trader for a bank and continued his studies instead, eventually earning a doctorate from the London School of Economics.

“I just couldn’t see myself doing those sorts of things,” Cripps says. “It really is much more fun to come in and do something you want to do everyday. And the fact that someone is going to pay you to do it is unbelievable.”

Cripps climbed up the academic ladder in England, eventually holding a professorship at the University of Warwick.

He was living what he describes as “middle-class bliss,” when a letter arrived from Stuart I. Greenbaum, Ph.D., the Bank of America Professor of Managerial Leadership and the Olin School dean at that time.

Greenbaum had heard of Cripps through some mutual acquaintances at Northwestern University, and he asked Cripps if he would want to come teach at Washington University for a year.

“This was extraordinary because I had spent a lot of time writing letters to people in America asking if I could come visit and it never worked out,” Cripps says.

“My kids were all at the right age where they could miss a year of school if necessary, so it was pretty much now or never.”

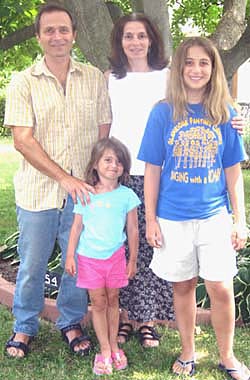

With a bit of trepidation, Cripps, his wife, Louise, and their three children packed up the house and made the journey across the pond.

Everything worked out even better than expected, Cripps says, for himself as well as his children.

“The boys, Edward and Robert, were teenage boys with English accents in an American high school,” Cripps says. “They probably thought they’d died and gone to heaven; there were cell phones, cars and pretty women. The only thing they couldn’t do was drink beer.”

Edward, now 22, and Robert, a 21-year-old WUSTL student, fit easily into American culture, revealing their British blood mostly when they’re out on the soccer field. Cripps’ daughter Grace is 13 and one year shy of starting high school.

Since moving to St. Louis, the Cripps family has grown. Daisy was born in 2000 and that, Cripps quips, gave Louise something to do that first year.

These days Louise spends half of her time working with a friend in property management and the other half working as a homemaker.

After that first year, Cripps decided to stay at the Olin School. He says he enjoyed teaching business students who were different from the economics majors he taught in England. Cripps also was surprised to discover practical applications for his skills.

“It was weird because I had spent my time doing theory, which is very unpractical,” Cripps says. “But at the same time, I discovered I actually could do something that was useful,” Cripps says. “And beyond the students, I was — am — absolutely impressed by my colleagues. It was thrilling to be around so many great academics that everyone knows about.”

His colleagues were — are — equally impressed with Cripps. Glenn MacDonald, Ph.D., senior associate dean and the John M. Olin Distinguished Professor of Economics and Strategy, says Cripps stands out because he has high standards for himself, his students and other people’s scholarship.

MacDonald says everything Cripps publishes is very high quality. All that, and he’s a really nice guy, too.

“He’s proof that you can be nice and have high standards,” MacDonald says. “Martin definitely hands out the criticism. But he’s such a nice guy that you know the critique comes from a good place and that turns out to be quite constructive.”

MacDonald also describes Cripps as witty, an omnivorous reader with a depth of knowledge that makes MacDonald envious. However, MacDonald says, he can’t be too envious because Cripps is so likeable.

That seems to be the opinion shared by nearly everyone who meets him.

Katie Morrow is administrative assistant for Cripps — as well as 11 other business school professors. Morrow says working with Cripps is easy; he treats her with respect and he doesn’t demand an inordinate amount of work. What’s more, Morrow says, he keeps her in stitches.

“He’s very comical,” Morrow says, recalling a risqué tale he shared recently. “I’ve never seen the guy stressed, although I have noticed he can’t sit still very well.”

|

Martin Cripps Born: April 25, 1960 Nationality: United Kingdom Family: Married to Louise. Children: Edward, 22; Robert, 21; Grace, 13; Daisy, 5. Cripps says he ascribes to the sentiment expressed by T.H. White in the novel The Once and Future King: learning is the only thing ” … which the mind can never exhaust, never alienate, never be tortured by, never fear or distrust and never dream of regretting. Learning is the only thing for you. Look what a lot of things there are to learn.” |

Indeed, sitting at his unusually clean desk in his unusually Spartan office, a conversation with Cripps is a veritable physical activity. He frequently curls a leg up to his hip and fiddles with his foot. Then he’ll shift forward placing both hands on the desk when he’s really excited about something — like the history of Counter-Reformation Spain. Or he’ll lean back and stretch out to contemplate an answer to some question.

Cripps is athletic, says MacDonald, referring to Cripps’ prowess at squash. MacDonald says he’s also competitive, which is evident from the odd rivalry he has with his co-authors to see who can last the longest riding their bikes to work — no matter the weather.

“He’s the anti-British academic,” MacDonald says. “The stereotype of an English professor is having an office with junk all over the place, books on the walls and elbow patches on his jacket. Martin is completely the opposite.”

Still, MacDonald says, Cripps has maintained a few British traits. He still calls sweaters “jumpers” and trucks “lorries.” And — while it might not be a purely national characteristic — Cripps is incredibly self-effacing. MacDonald describes Cripps as an extrovert who doesn’t like being the center of attention.

“He was squirming for months prior to his installation (as the John K. Wallace and Ellen A. Wallace Distinguished Professor of Managerial Economics),” MacDonald says. “It’s so odd because when you talk to him one-on-one he’s so funny and lively, but publicly he doesn’t want to be noticed.”

Which means that for anyone who feels the slightest twinge of jealousy over Cripps’ good fortune and charming qualities, one can take just a small amount of gratification from knowing that Cripps is cringing right now — not at all comfortable being featured so prominently in this issue of the Record.