In the mid- and late 1960s, the Black Arts Movement emerged as the aesthetic and spiritual corollary to the Black Power philosophy. Spurning assimilation, the movement took often-militant pride in African-American history, culture and traditions, and in so doing laid much of the groundwork for contemporary multiculturalism.

In St. Louis, the Black Artists’ Group (BAG), which flourished between 1968-1972, gave rise to a host of nationally recognized figures, including Oliver Lake, Julius Hemphill and Hamiet Bluiett of the World Saxophone Quartet; trumpeter Baikida Carroll; painters Emilio Cruz and Oliver Jackson; and stage directors Malinké (Robert) Elliott and Muthal Naidoo.

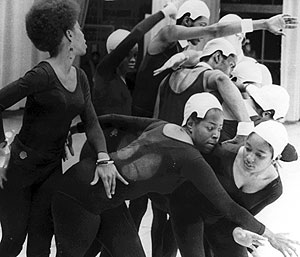

“The Black Artists’ Group was a seedbed for artistic innovation,” said Benjamin Looker, author of 2004’s “Point From Which Creation Begins”: The Black Artists’ Group of St. Louis. “But unlike most other artistic collectives of the period, BAG was fundamentally committed to a collaborative interweaving of its members’ diverse artistic mediums. The organization brought together and nurtured an array of African-American experimentalists, in disciplines ranging from music, theater and dance to visual arts, poetry, and film.”

On Feb. 16-17, the Department of Music in Arts & Sciences will host a symposium and concert series titled “Music and Musicians of the Black Artists’ Group in St. Louis,” dedicated to the influential yet little-remembered collective.

The events come amid a dramatic resurgence of interest in BAG’s history and music: In addition to Looker’s monograph, a series of rare BAG recordings has recently been reissued on the Ikef, Quakebasket and Atavistic record labels.

“The astonishing artistic richness of the Black Artists’ Group deserves to emerge into full view,” added Looker, a WUSTL alumnus and Yale University doctoral candidate who first encountered BAG’s legacy while pursuing undergraduate degrees in music and urban studies. “Their work represents a unique and engaging effort to discover an artistic voice adequate to the social and cultural dislocations of its time.”

In many ways, BAG represented the convergence of two parallel trends in the African-American arts world: free jazz and experimental theater.

In the mid-1960s, St. Louis free-jazz musicians were largely confined to informal concerts on Forest Park’s Art Hill and at the home of Oliver Lake. Yet in 1967, The Lake Art Quartet debuted at the Circle Coffee House in LaClede Town, a federally funded, mixed-income housing complex at the heart of the city’s counterculture.

The following year, Lake, Malinké Elliott and others staged Jean Genet’s controversial play-within-a-play The Blacks (1958) — in which a group of African-Americans, possibly actors, re-enact the possibly fabricated murder of a white woman — at Webster College’s Lorretto-Hilton Center.

“With its aggressive posture toward its audience, its treatment of race and color and its integration of music and drama, the production embodied the hybrid nature that would characterize the BAG enterprise,” Looker said.

“Productions during these years ranged from sharp satires dramatizing immediate issues of the local community to sweeping ritualistic pageants that laid out broad visions of black survival, spirituality and nationhood.”

As BAG expanded, it attracted funding from the Danforth Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation and others.

In July 1969, the group obtained, for an annual rent of $1, a building at 2665 Washington Blvd., in the heart of the inner city. It soon housed living quarters, performance/rehearsal space, a painting studio and teaching facilities for dance, theater, music, film, creative writing and visual arts.

Yet at the time, “The atmosphere in St. Louis was not particularly receptive to the new sounds being explored by Lake, Hemphill and their musical comrades,” Looker said.

For example, Hemphill’s LP Dogon A.D. (1972), released on his own Mbari record label, was praised by jazz critics yet found only limited distribution and virtually no radio play.

By the early 1970s, leading BAG musicians had grown frustrated with the lack of opportunity and relocated to Paris and New York. Lake, Hemphill and Hamiet Bluiett quickly carved out roles in New York’s underground “loft-jazz” scene and soon captured international acclaim as co-founders of the World Saxophone Quartet, hailed by The New York Times as “probably the most protean and exciting new jazz band of the 1980s.”

“BAG continues to be most widely known for the cadre of jazz improvisers and composers that it fostered — artists who embraced a modernist ethos that remained grounded in a black musical heritage,” Looker said.

“But a few constant themes do emerge from the collective’s repertoire: arts as a potent method of community engagement; institution-building as a response to the social and economic forces rending the fabric of urban life; and an aesthetic vision focused on black heritage and tradition in the context of new forms and techniques.”